To mute sound, hit pause above thumbnails.

In late 2009, I came to Nord Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to do research for a story on women's issues. DRC is a huge and troubled country, bordering nine others (ten if you count Tanzania, separated only by a lake). Susceptible to tribal conflict from the entire region and home to hundreds of thousands of displaced people, it gives its name to the deadliest war in African history--the Second Congo War--which began in 1998 and involved eight countries, more than 20 military groups, and left more than 5 million people dead, many from disease. Though the war "officially" ended in 2003, its consequences are inescapable, and as I write this, fighting has broken out in the east between the army and a group its defectors calling themselves the M23 movement, causing 7,000 people to flee over the border into Rwanda.

I'm from Warsaw, Poland, which 70 years on still carries the scars of its own devastation at the hands of the Nazis in World War II. It would have been easy to place my visit in the context of the "Heart of Darkness" vision of Congo. But what I was looking for was a way to see everydayness in the extremes, and I found it in an unexpected way.

I was based on the eastern edge of DRC, which had its own tribal war from 2004-2009, the Kivu conflict, fought between the Congolese military, and Hutu and Tutsi factions from Rwanda, the tiny, genocide-plagued country just 30 km to the east. It is this area that is now the most tenuous, with fears of rebellion against President Joseph Kabila's government as serious as they have been since I was there.

I arranged my trip through a contact with a modest and brave group of Polish missionaries who had been in Congo for 30 years. Their knowledge and experience made everyone with a cocky attitude pale.

In my first few days, while I was walking around smoking cigarettes and getting my bearings, I was approached by some local youngsters. I was a curiosity for a couple of reasons: Whites are not frequently seen here and, as I later learned, women don't smoke. (The local women who do are often prostitutes.) A few college age boys approached me, speaking a mix of English, Congolese French and Swahili. My English is better than my French, but I could understand them, more in fact than I sometimes let on. At first, they just wanted to know who I was and what I was doing there. I told them I was a journalist.

They were courteous and respectful. They wanted to present themselves as strong, confident, and attractive. Their clothes and shoes were cheap, mostly Chinese made sportswear knockoffs, but they wore them with pride. They had rings and some even had thick fake gold necklaces with pendants. And of course they carried cell phones. The "look" was crucial, even if it was just a facade.

Not surprisingly, the reality was that many of them were having a hard time. Some couldn't afford the $50-70 per semester school fees and were being forced to drop out. Others were graduating, with little hope of finding a job. Some of them even had a fatalistic attitude that is chilling for me to think about as I listen to the news the last few weeks. Eimable, 20, told me that when the time comes, he will go to the forest to join military group and become a colonel, or general. "Other countries will have no power to stop me. When I will manage to seize territory, occupy few villages, learn to kill, rape, burn houses and destroy everything, others will start to respect me." For the time being, he was studying pedagogy at the Institut Supérieur Pédagogique (ISP) in Rutshuru.

One of the only ways these youth found inspiration was through music: rap and hip hop. They listened to it on the local radio, and when the Institute's Internet connection was working, they watched videos on Youtube of American and French rap groups. They said they felt a connection to the music because it is black music sung by blacks from the ghetto, from nowhere. The expression of anger on issues of social justice and rights resonates with them. Their clothing, ghetto celebrity style, started to make more sense.

Many of the youth I met had actually formed their own bands, and had organized a concert, which they invited me to attend. And I did. It turned out that this was quite an important event with cash prizes for winners around $100. For many of us that's nothing, but in Congo, it's a decent bounty. (The average monthly salary for a teacher is around $50.)

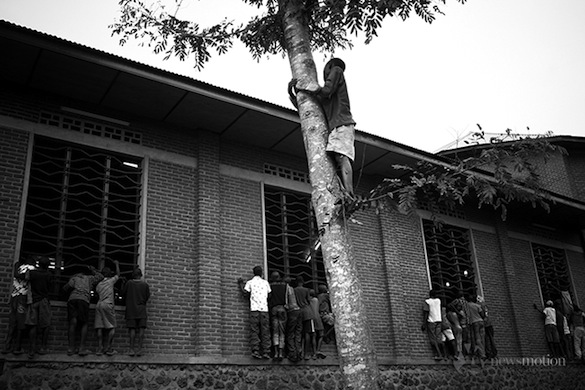

The event took place at the Kaoze Community Center (pictured below), in the village of Rutshuru, Nord Kivu, and lasted for two days.

Rutshuru, a few hours on a teeth-rattling road from the province's capital Goma, is often the site of conflict. At dusk, people hurry to the relative safety of their tiny homes, which are made of mud, straw or occasionally wood with aluminum roofs. Tickets to the show were about 50 cents, but it was still too expensive for some, who crowded around the building on tip-toes, peering in through windows. One of them climbed a tree in hopes of a better view.

Due to security concerns, the shows could only take place during the day. But the concert hall was full of the joy and euphoria one might expect when teenagers anywhere let loose. Using pre-recorded tracks because they can't afford instruments, and occasionally sharing each other's shoes so the performers could be fully dressed, they sang and danced until 6 pm, when darkness began to set in and the place cleared in minutes.

Not that there weren't security concerns during the shows. The population in this area is a melting pot of tribes. My French was good enough to pick up that some band members didn't want me talking to bands from other ethnic groups, who they often consider rivals. In order to avoid potential clashes at the concert, the results of the contest were withheld until after the last show ended and were announced on the radio.

Though the odds against it are overwhelming, all of these youngsters dream of achieving success and fame through their music. Their idols and inspiration come mostly from France and the U.S. Joseph (Icizampa), a member of the B2K band proudly wore a fake gold necklace with a "$" stamp, even though the pendant was damaged and misshapen. But there are few places to record, and fees at the studios that do exist are too high for them to afford.

The winning band, Dangerous, managed to record its song, Pata Kitu ("Get Something," in Swahili), in a studio in Goma. (Listen or share the song.) Below, Dangerous band member Mafloow, does a Michael Jackson move.

After the concert I started spending more time with the musicians. I was often the one wearing the cheapest clothes, but no matter what I did to downplay my otherness, I was often the center of attention, and always being asked for something: either to marry someone, or to give money or candies. Muzungu in Swahili is what you call a white person, but it literally means someone with money. Even if you are not, you are seen as rich. Even if you don't give away money, you are presumed to be doing so. Envy between neighbors exists, and my presence might have caused unexpected troubles. I was once told that it was easy to poison neighbors' kids just for revenge and I kept that in mind all the time. I never judged them because I am not sure what I would do if I were in such situation. I think of Zimbardo's Stanford Prison Experiment that proved any of us is capable of carrying out the most horrifying actions. People from Nord Kivu live in a reality we can't even imagine. Many saw family members and friends killed, kidnapped, tortured and raped. They fled their homes, lived in Internal Displacement Camps. In 2009, out of Nord Kivu's 5.7 million people, more than two million were displaced immigrants. Armed militias and thugs, some of whom are mentally ill due to the brutality they have witnessed, roam the area, most carrying AK-47's that they can easily purchase for $20-$30.

The current situation is changing by the day. In Rutshuru, there have been strikes and protests against local authorities. Major desertions from the Congolese army FARDC have taken place, and president Joseph Kabila's authority is being questioned. Violent clashes between army and rebel groups have caused fear among the townspeople, who are frustrated by the lack of action by the UN mission. Everyone remembers 2008, when people gathered in front of the gates of the UN base in the hopes of protection from massacres of Hutu by a rebel Tutsi led group, only to be killed almost right in front of the building. There is also growing anger about what they see as a huge scale robbery of their natural resources. Minerals, such as tin, are abundant, and they are being mined by international companies using local labor and for huge profits that enrich only foreigners.

The Western media typically treats the conflict in eastern Congo as just another tribal conflict. "All I want people from outside to know is Congolese are not killers," Bineli, 21 , a member of Kashmal band told me.

We tend to simplify to make easier what we don't understand. I remember when I first went to the Internally Displaced Camp near the U.N. peacekeepers base in the outskirts of Kiwanja. My friends pointed to a demolished house not far away. They were pointing to the place beyond which no one could go without risking their life. It was less than 700 meters from where we stood. While we were talking about the dangers and the continuing strife, kids from camp were running, dancing, turning somersaults and laughing. In the moment, I found the juxtaposition absurd. But I came to think I was wrong. The people I met have such strong spirits and ability to adapt to quickly to circumstances that I couldn't help but be awed.

THE B2K BAND:

Amani, 17, (center photo, front), lost all his family during two decades of war. He lives with his cousin Moses in Murambi, a neighborhood in Rutshuru.

Serge, 16, (center photo, far back) dreams of living in US and marrying a plump white woman.

Moses, 17, (left photo, and far right with necklace), says the color of the blood doesn't depend on skin color - it's always red. He hates tribalism, but refuses to answer why he hates certain bands from town.

DANGEROUS BAND:

Justin, 21, (left photo, third from left) often imagines himself relaxing on a sofa, watching TV or playing computer games. "What make me very pleased are modern things," he says.

Esperence, 18, (left photo, lying in foreground) the only moment that makes her happy is when she is with the family that survived years of conflict: with her father and siblings. She thinks people from outside little understanding what's going on in Congo.

Eric, 22, (right photo, singing) wants to forget about his past. His brother was recently killed, and he thinks he cannot move on, which horrifies him.

Vianney, 19, wants to forget suffering.

OTHER BAND MEMBERS:

Christian, 16, (Lille Cent band, pictured at left without Christian; at right, Christian in front), gets angry when someone tells him he is wrong when he knows he is right.

Danielo, 20, (Young Boys band), fell in love with a girl from another tribe and faced serious social consequences. Later he wrote a song about it.

Tony (27) a member of Kashmal band hates flippancy and being disrespected.

For France (22), an associate of Kashmal and technician from radio La Colombe, only idiots are unable to progress, evolve. "But we after all... are intelligent".

What I recorded is just a glimpse of the important stories to be told. It is a work in progress. I plan to launch crowd-funding campaign this autumn to support another trip to Congo later this year or in 2013. I am also considering multiple formats for producing this story (a documentary and book, along with the multimedia.) I want to help find new ways to to give something back to the community, and to activate and promote their creativity.

Watch "War Songs," a short documentary on the youth rappers:

Agata Pietron is an independent photographer, journalist, cinematographer and graphic designer currently based in Warsaw, Poland. She received her Master's Degree from the Cultural Studies at University of Warsaw, and studied Photography in European Academy of Photography and Cinematography in Academy of Film and Television. She has worked on social projects in Eastern Europe, Latin America, USA and Central Africa (DRC, Rwanda). Her works have been exhibited in Poland and abroad. One of the works from "one degree of warmth" story was acquired by Princess Royal Anne collection. producer/editor: Julian Rubinstein