When Bill Babbitt realized his PTSD-afflicted brother Manny had committed a crime he agonized over his decision -- should he call the police?

Our short documentary Last Day of Freedom (currently nominated for an Academy Award) tells Bill's story as he stands by Manny, a war-ravaged Vietnam Veteran, through his arrest, trial and execution.

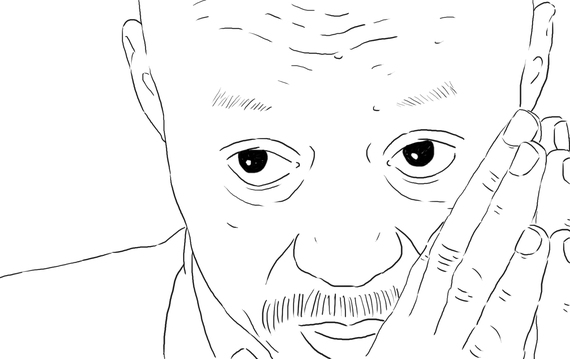

Created from over 30,000 hand-drawn images, the film is a portrait of a man at the nexus of the most pressing social issues of our day -- inadequate Veterans' care and mental health access, deep-seated inequality and racism, and the reality of a broken criminal justice system.

Bill's powerful narrative unfolds like a classical tragedy, revealing Manny's trial and execution for what it is -- one of the most egregious miscarriages of justice in the modern era of the death penalty.

The animation illustrates Bill's remembrances and visualizes the inexorable process that brought Manny from his childhood home in Massachusetts to San Quentin prison, by way of Vietnam: Manny and Bill dig for clams on the Cape Cod seashore; Manny is hit by a car in adolescence and is never the same after; Manny signs up for the Marines at 17. "He couldn't pass the test," Bill says, "so they gave him the answers. He found himself at war."

Returning from multiple tours in Vietnam (where he saw some of the worst fighting in the entire conflict at Khe Sanh), Manny begins the now familiar march of combat-traumatized Veterans towards homelessness.

He suffers hallucinations of helicopters and bombings. He is diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and institutionalized repeatedly. Without a viable support network, he lives on the streets before relocating across the country to live with Bill in Sacramento, a move that would ultimately prompt Bill to make his fateful decision.

And though he questioned whether he was doing the right thing, Bill went to the authorities with his suspicions about what Manny had done. The police, who Bill trusted entirely, hailed him as hero and offered assurances that Manny would get the help he desperately needed.

With Bill's assistance, Manny was arrested. He was charged with a capital offense and sentenced to death by an all-white jury. His lawyer was reportedly drunk throughout most of the trial. Finally, after a lengthy appeals process, he was executed on his 50th birthday -- leaving Bill to live with the double burden of the preventable horror of his brother's crime and the guilt of his execution.

Bill's story is particularly heartbreaking but his situation is not extraordinary. The details of Manny Babbitt's life reflect the data about who gets the death penalty in America:

• Manny was Black.

Bill describes his brothers' lawyer: "I asked the lawyer 'I don't see any Blacks being seated on the jury.' He said he did not trust -- he used the N word. I guess he figured he could use the nigger word and feel comfortable"

According to the Death Penalty Information Center "the odds of receiving a death sentence are nearly four times higher if the defendant is Black." As such, since 1982 not a single year has gone by without a Black man being executed in the USA. When the same group of researchers calculated the influence of race on sentencing it found that "the capital sentencing statute has operated as though being Black was not merely a physical attribute, but as if it were one of the most important aggravating factors actually justifying the death penalty."

• Manny was a Veteran.

"Manny traded his hooch in Vietnam for a cardboard box on the streets of Providence Rhode Island."

Much has been made of the VA's many public failures; to these many grim statistics (47,000 homeless Veterans, nearly half having served in Vietnam like Manny, about 45 percent black or Hispanic despite making up around 14 percent of the total Veteran population), add the November 2015 report which estimated that there are "at least 300 veterans are on death row nationwide, representing about 10 percent of the nation's death row population." Like many of these individuals...

• Manny suffered from TBI and PTSD.

"Manny traded the war on the battlefield for the war in his head...my little brother was out there in limbo land, fighting these battles."

The relationship between trauma and subsequent violence is well documented. This connection is particularly conspicuous on Death Row. Recent research indicates that "nearly all Death Row inmates suffer from brain damage due to illness or trauma, while a vast number have also experienced histories of severe physical and/or sexual abuse."

• Manny was poor.

Almost without exception, the common denominator among death row inmates is poverty. The ACLU states that "economic disparity is the chief determining factor between those who live after being accused of a crime and those who are executed."

Three decades after Manny's trial, the death penalty is still disproportionately applied to minorities, the poor, and the mentally ill. This longstanding preference for punishment over prevention or rehabilitation when the most vulnerable among us are concerned underscores the link between the various forms of inequality we face today. We are proud to stand with Bill Babbitt when he says "I thought that justice would prevail and it did not. So here I am, here I am implacable, I'm gonna tell it."