A recent string of suicides by foreign maids working in Lebanon is once again drawing attention to the rampant abuse of migrant domestic workers in the Middle East.

Since October, at least 11 women have either hanged themselves or fallen from high buildings in Lebanon. Six of their deaths have been reported in local newspapers as suicides. The other five have been controversially referred to as "work accidents."

Their tragic deaths reflect simply a spike in what is a steady trend: roughly one migrant domestic worker dies every week in Lebanon, either from suicide or from a botched attempt to escape an employer, according to a 2008 report from Human Rights Watch (HRW).

Last week I spoke to HRW in Lebanon and wrote this in a story for CNN.com:

"This pattern [of abuse] is on going," Houry [HRW Researcher] told CNN, citing "bad working conditions, isolation and a feeling of helplessness that comes from lack of recourse," as the sources of desperation that can drive these women to their deaths. ...

There are more than 200,000 migrant domestic workers in Lebanon -- roughly one per every four families. Overwhelmingly they are women in their 20s and 30s who come alone from the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Nepal and Madagascar, to earn money to support families back home.

According to HRW, more than one third of foreign domestic workers in Lebanon are denied time off and more than 50 percent work at least 10 hours per day.

A 2001 International Labor Organization (ILO) survey of Sri Lankan domestics in Lebanon found that 88 percent were given no time-off. Among the 70 respondents, nearly 30 percent said they were not given enough food to eat.

Workers are also frequently locked-in (31% of female domestic workers said their employers did not allow them to leave the home in a 2006 survey).

Under such conditions it's unsurprising that a constant stream of runaways keeps both relief agencies and embassies busy around the clock, not just in Lebanon, but in Jordan, Saudi Arabia (see "As If I'm Not Human" - a report on abuse in Saudi) and several other states in the region.

This week I spoke to the labor attaché at the Embassy of the Philippines in Beirut who told me there were currently 152 runaways living in the building, most sleeping on mattresses on the floor, waiting to be sent back to Manila. The government of the Philippines (among others) has banned its citizens from emigrating to Lebanon for domestic work because of this history of abuse, but thousands still enter illegally every year.

While the majority of domestic workers don't endure such desperate conditions, the situation is intolerable for the unlucky minority who do. The reason this type of abuse can continue to occur in Lebanon, as it does in neighboring states, runs deep into the legal and social structures of states in the region.

In other words, across the Middle East a combination of weak labor regulation and cultural norms conspire against the welfare of migrant domestics and condone exploitation so extreme that it can be considered modern-day slavery.

- First, the laws in most of these countries do not recognize jobs in private homes as formal labor -subject to basic rights (e.g. a day off) and regulation (e.g. a contract).

- Second, migrants are only granted entry under the "kefala" ("kafeel") sponsorship system, which ties a worker to their sponsor in an ownership-like arrangement that frequently violates international human rights norms (the right to free movement, the right to retain one's passport, the free will to leave a foreign country when one chooses...). It also means migrants have few options for legal recourse because they have almost no rights in the justice systems of Middle East courts.

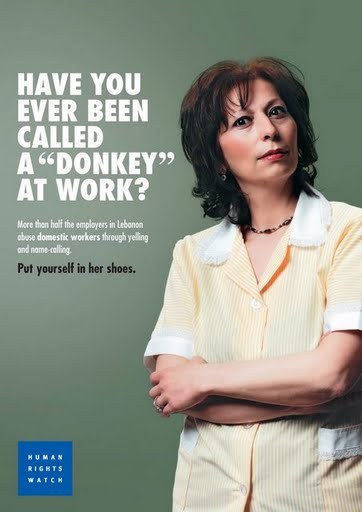

- Third, as predominately female and foreign, these domestic workers are frequently subject to racism, xenophobia and misogyny that tolerate mistreatment, particularly verbal abuse. For example, maids in Lebanon are commonly referred to as "donkeys" by their employers. Moreover, an HRW investigation from this past summer found that foreign maids were widely banned from swimming in pools in Lebanese resorts, reflecting racist norms and mythologies of contamination.

This photo is from a HRW awareness campaign in Lebanon called "In Her Shoes" which seeks to draw attention to the mistreatment of domestic workers.

This photo is from a HRW awareness campaign in Lebanon called "In Her Shoes" which seeks to draw attention to the mistreatment of domestic workers.

Currently the state of Lebanon is working to improve legal protections, and have instituted a unified contract for all domestic workers in the country. This contract stipulates a minimum wage, a mandatory day off each week, the right to paid on time, and other very basic rights.

For the meantime though, progress has been put on hold because of political stalemate after the Lebanese elections. "We already have submitted a counter proposal to be reviewed by the Interior Ministry," but are waiting said the Filipino labor attaché. He's also hoping the bureau of immigration will start functioning again so that some of the 152 women at the embassy can start being sent home.

Check out filmmaker Carol Mansour's documentary "Maid in Lebanon" and listen to domestic workers in Lebanon tell their own stories.

For detailed information also refer to the ILO's report: "Gender and Migration in the Arab States: the Case of Domestic Workers."