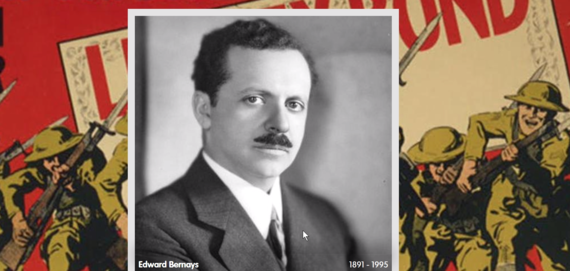

EDITOR'S NOTE: It is hard to imagine a world without ubiquitous communication aimed at molding public opinion. Yet public relations didn't formally exist until roughly a century ago. The man credited with creating the field of PR, Edward Bernays was one of the most colorful characters of the 20th Century. This is his 125th birthday.

Without him, the great Caruso might not have become the toast of the land. Sigmund Freud's work might not have been translated for American readers for another decade. A generation of children might have grown up with dirty faces, and a generation of women might have gone on smoking cigarettes behind the shed.

The rich and the powerful turned to him for advice. His clients included Presidents Coolidge, Wilson, Hoover, Roosevelt, Truman and Eisenhower. Others equally well known included Thomas Edison, Eleanor Roosevelt, Enrico Caruso on his first visit to America, and the dancer Nijinsky.

Those he rejected were notorious: Adolf Hitler, Gen. Francisco Franco, and former Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza.

"Hitler wanted me to create a campaign for the German train system," Bernays deadpanned. "Apparently, he did not know that I'm Jewish."

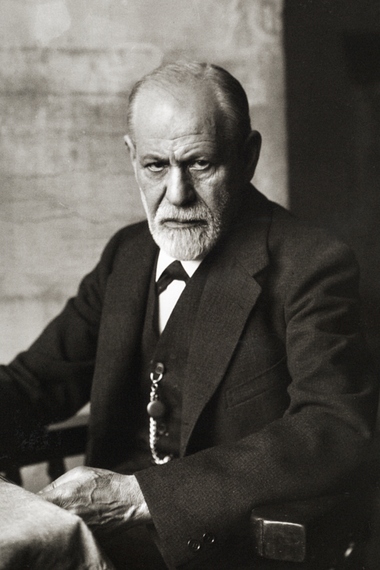

Today, Edward Bernays is known as the Father of Public Relations, and in large part the field of PR was his idea. Many of the ideas at the core of his beliefs came from his uncle, the Viennese psychiatrist Sigmund Freud.

Freud family photo, 1878. His mother Anna is second from left, back row, next to Sigmund Freud.

"People sought him out not just because of what he could do for them but to keep their competitors away from him," said Dr. Otto Lerbinger, chairman of the school of public relations at Boston University. "He always came up with a different angle."

A bibliography of books and articles commenting on the campaigns he engineered fills nearly 5,000 pages, and lists more than 4,000 separate entries. Until the end, he relished reminiscing about them.

His success was so great that the War Department hired him to spearhead recruitment to the Armed Forces and donations to War Bonds, allowing him to mold many of the era's most famous posters.

"Dodge was coming out with a new automobile in 1928," he said, "and they asked me what I could do to bring it to the public's attention. Those were the days of silent films, and it occurred to me that no one had ever heard Charlie Chaplin's voice. So I got Chaplin and Gloria Swanson together," he explains.

Bernays arranged for the two to do a radio commercial, but not before taking out a highly publicized policy with Lloyd's of London insuring the star of silent movies against stage fright. "No one had ever heard Chaplin's voice," he said. When the time came, everyone stayed home to listen to Dodge Hour.

Bernays's goal, unique at the time, was to create events that contained his message and stirred media attention.

Mission accomplished.

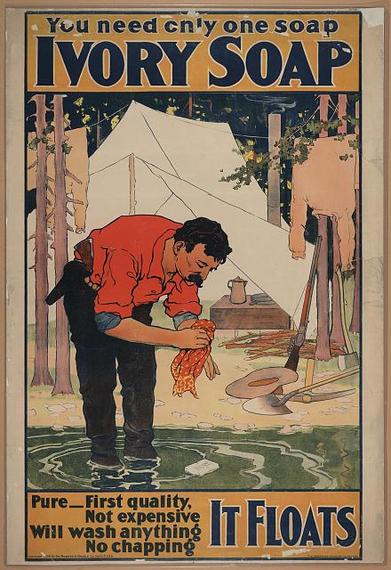

The soap campaign Bernays designed for Procter and Gamble in the early 1920s was one of his favorites - and illustrative of the unique way he developed to convey a message.

"The simple fact was that kids cried when they got soap in their eyes. Soap was something they hated."

To change that, Bernays persuaded schools across the country to participate in soap sculpture contests.

"It made it possible for the soap they hated to become something they loved, something that would gratify their creative instincts. Within a year, 22 million kids were involved in soap sculpture," he said.

Born in Vienna, Bernays came to the United States a year later. He married Doris Fleischman, a marital and business partnership that lasted until her death in 1980. The marriage created headlines when Fleischman kept her maiden name, and again when she became the first married American woman to receive a passport in her maiden name.

The public relations counseling firm they founded together was enormously successful. "For a long time, he was known as 'U.S. Publicist No. 1,"' said Lerbinger, who credits Bernays for teaching the first university course in public relations at New York University in 1923.

Bernays was never reluctant to discuss the revolutionary methods that helped him change the face of American public opinion In the 20th century.

"I never visited newspapers," he says. "I created circumstances."

During his lifetime, public relations became a multi-billion-dollar field. But when Bernays arrived on the scene before World War I, there were only press agents whose reputations were sometimes unsavory. Opinion research was unknown. "In those days, public opinion was considered philosophy. There was no psychology," he said in a 1984 in his living room in Cambridge, MA.

When Bernays began his career, sociology was in its infancy, and Walter Lippmann had just begun to define the term "public opinion." Bernays, meanwhile, concentrated on what he called "the American tribal consciousness." Bernays perceived at an early age that opinion could be molded.

With Eleanor Roosevelt.

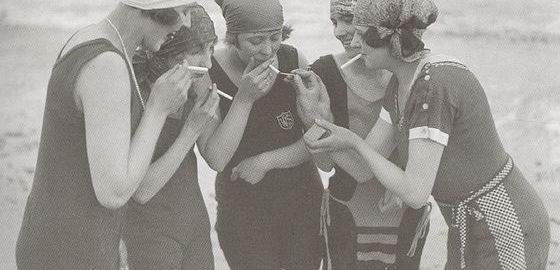

Bernays lived long enough to have his share of regrets. His campaign for the American Tobacco Co., for example, is one of them.

His task was to break the taboo against women smoking in public.

"The first thing I did was go to a psychoanalyst. He told me that for women, cigarettes represented man's inhumanity to women. So my idea was to get women to show their equality."

Women lighting up "Torches for Freedom," 1929.".

Bernays contacted actresses, models and debutantes across the nation. At the appointed hour, hundreds marched to places like Boston Common, Union Square in San Francisco, and Central Park in New York to light up "torches of freedom."

"This was before anybody knew cigarettes were carcinogenic," he said. "I later worked to get tobacco advertising off radio and television to ease my guilt complex."

Sigmund Freud, his mother's brother, sent him a manuscript while Bernays was in Paris accompanying Woodrow Wilson to the 1919 Peace Conference after World War I. Though Freud's books had been translated into English in Europe, they had not yet been published in America.

"Freud sent me a copy of Introductory Lectures in Psychoanalysis, and I took it and talked to a publisher I knew. Freud wrote me how public opinion is formed," he said. Freud's insights contributed to Bernays's 1923 classic, Crystallizing Public Opinion, which changed corporate and political communication forever.

Bernays had his critics, many of whom blamed him for introducing "mind control" to industry and the government. He was accused of using Freudian psychological insights for commercial purposes, especially in the form of subliminal advertising. Others criticized his work for the government encouraging young people to enlist during the 1st World War.

The campaign he conducted on behalf of the United Fruit Company is one of his most controversial. In a series of ads published in the U.S. media, the president of Guatemala, Jacobo Arbenz, was described as a communist.

Arbenz was ousted in a coup d'état engineered by the United States Department of State and the Central Intelligence Agency. It was led by the brothers John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles, both of whom had major interests in United Fruit. Bernays's role in the unsavory affair led to disagreement over his legacy.

Bernays insisted that what he had done was change public relations into a profession with academic underpinnings.

Before his death in 1995, Bernays turned his attention to the generation gap. "Very little has been done to bridge that gap," Bernays said. "When you consider that by the year 2040, up to 40 of the nation's population will be over 65, that's a problem."

"In American society," he said, "It Is vital that every institution adjust to public needs, hopes, desires, aspirations. The only way this can be done is through research. The maladjustment between the institution or product and Its public must be discovered.

"Only when that maladjustment is known," he said, "can the adjustment be completed."

OurPaths.com is a place to celebrate extraordinary lives.