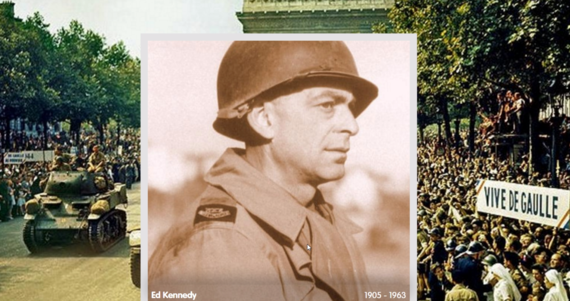

In 1945, the AP fired its lead correspondent in Europe for breaking a major story - the end of war in Europe. Seventy years later, more than 100 of his journalism heirs are battling to repair his reputation. This week they nominated him posthumously for the Scripps Howard Award for distinguished reporting.

By Christopher B. Daly

I was very pleased to see that my old employer, The Associated Press, finally did the right thing and apologized to a great correspondent who was wronged in 1945 as he broke the news about the end of the fighting in Europe. And that this week reporters are trying again to make it right.

The apology came on the 67th anniversary of the surrender of Germany.

The date of the official celebrations was May 8, 1945, known as V-E Day, for victory in Europe. Much fighting remained to be done in the Pacific, where Japan was still refusing to recognize the now-inevitable Allied victory.

In early May, 1945, the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) command selected 17 correspondents from the world's press and flew them to Reims, France to witness the surrender on behalf of the rest of the press and the people of the world.

There were few Americans in the group. In fact, not a single reporter representing a U.S. newspaper was present.

According to the allied military commanders, the news was to be embargoed; that is, you had to accept a deal. In exchange for access to the event, you had to agree to hold the news until the Army said you could release it. The SHAEF press officer said:

"I pledge each one of you on his honor as a correspondent and as an assimilated officer of the United States Army not to communicate [the news] until it is released on the order of the Public Relations Director of SHAEF."

Was it really an agreement?

It remains unclear what constitutes an "agreement" under such conditions (what were the correspondents supposed to do -- get up and walk out of an airplane?). Whatever the case, they proceeded to witness the ceremony.

General Alfred Jodl, chief of operations for the German high command, signs the surrender document at Eisenhower's Little Red Schoolhouse headquarters in Reims. Photo Copyright The Associated Press.

General Alfred Jodl, chief of operations for the German high command, signs the surrender document at Eisenhower's Little Red Schoolhouse headquarters in Reims. Photo Copyright The Associated Press.

The surrender by the German high command came in the early hours of May 7. Ordinarily, you might expect that the surrender would touch off immediate celebrations.

Not so fast.

The press officer announced that a news blackout was in force until 8 p.m. the next day, when the news would be announced simultaneously in Paris, London, Moscow and Washington. As it turned out, Stalin was behind the delay, insisting that he be allowed to make a show in Berlin.

The reporters protested to the SHAEF press officer, but to no avail.

Among the press corps, one of the most upset was Edward Kennedy -- not the late Democratic senator from Massachusetts but a man by the same name who was the chief correspondent in Europe for the AP.

Kennedy was in a special position. Kennedy knew that his AP account of the German surrender could probably reach more people on the planet than any other. He knew no other American reporters were present, and probably felt Americans should be among the first to hear the news. Besides, he figured, no embargo on such a momentous story could hold for that long. (Nor, perhaps should it.)

World remains unaware

Still, the world knew nothing of the surrender. Still, soldiers in Europe kept shooting at each other.

When they landed in Paris, Boyd Lewis of United Press got the first jeep from the airport to the Hotel Scribe, the outpost for most of the press corps. When Lewis got to the press center, he tried to tie up all the available telegraph outlets. James Kilgallen of INS beat Kennedy to a phone by throwing his typewriter at Kennedy's legs.

Then Kennedy heard that SHAEF had permitted German radio to announce the surrender. Kennedy went to the censors and announced that he was breaking the embargo. Using a telephone, he called the AP bureau in London and dictated the following lead:

REIMS, France, May 7 (AP) -- Germany surrendered unconditionally to the Western Allies and the Soviet Union at 2:41 a.m. French time today. The surrender took place at a little red schoolhouse that is the headquarters of Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Within minutes, the news was flashed to the world, and wild celebrations began. SHAEF was furious and suspended AP filing facilities throughout Europe. The rest of the press corps was furious, too. More than 50 correspondents signed a protest to Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower, calling Kennedy's action "the most disgraceful, deliberate and unethical double cross in the history of journalism."

AP's president apologized to the nation. AP brass told Kennedy he could keep his job if he admitted he had done wrong.

He wouldn't and was fired.

Ethical questions still reverberate

More than 70 years later, Kennedy's decision to publish, and the AP's decision to fire him, still raises hackles. In 2012, a small group of supporters nominated Kennedy for the Pulitzer Prize. The effort failed. The same year, prompted by the tireless efforts of Kennedy's daughter Julia to gain justice for her father, Tom Curley, then President and CEO of the AP, apologized for Kennedy's firing and said his actions were exactly what they should have been.

Listen to Tom Curley's rationale for supporting Kennedy's decision

The following year, the group gained the support of more than 100 distinguished journalists, media executives and historians and nominated Kennedy for a Special Citation Pulitzer Prize. It failed a second time.

Ward Bushee, retired editor of the San Francisco Chronicle, said the Pulitzer rejection "demonstrates that even 70 years after his famous scoop Ed Kennedy remains a figure of controversy." Bushee is among those nominating Kennedy for the Scripps Award this week.

Click here to see the full tribute to Ed Kennedy on OurPaths.com

What might seem amazing today -- aside from the lack of cell phones and other forms of instant global communication -- is how unanimously the correspondents fell in line with the military. Today, I dare say, U.S. reporters would be at least split about the ethics of something that they knew to be both true and life-saving.

-30-

Chris Daly is a professor at Boston University. A former Associated Press reporter and editor, he contributed this story to OurPaths.com.