If you ask almost anyone under or over thirty who is right up there with their favorite artists, chances are they will tell you Salvador Dali. Certainly, he is, along with Picasso, among the most famous names of the twentieth century. Though the cognoscenti may have their noses in the air about Dali, a current exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (born at the Tate Modern) on the connection between his films and his art makes clear that this man was a fecund genius. Critics claim that Dali's showmanship, his relentless quest for fame and his unerring instinct for self promotion got in his own way. But he prefigured so many contemporary artists: not only Warhol but Damien Hirst, Matthew Barney, Jeff Koons, Julian Schnabel et al, artists for whom the canvas was just not big enough and whose ego and drive propelled them to cut across all media into household names.

Though I had seen the exhibit in London and enjoyed it, I wanted to see it again in its new surroundings. On Sunday, when I got to the museum, the lines were deep and long, and it was exciting to feel the buzz-y energy that a truly popular artist can ignite.

Why is this long dead artist still such a perennial hit amongst so many? Dali's images are everything you always thought modern art was all about: psychedelic before we even knew what that meant, trippy and hippy, outrageous, sexy, filled with double entendres and wild juxtaposition; he may not have taken acid but it feels like he did. As one of the second wave of early surrealists, Dali was in the business of shock: he wanted to poke and prod preconceptions, substitute his own often outlandish imagery for the much tamer stuff going on in your own head. The paintings and films are rife with images that droop and confront, wilt and melt, but it's not just young people who relate to his in-your-face aesthetic.

The Surrealists were the original bad boys: brilliant, exceptionally daring, political (through all the "isms" ) and psychologically astute ( when Freud's theories began to influence almost everything), they were competitive but close knit: writing, dreaming, filming, painting and sharing ideas during the day, and then passing around the beautiful, talented women like so many after dinner mints at night.

Salvador Dali was both an amateur of film and a practitioner: his most successful works, Un Chien Andalou and L'Age D'or which have influenced almost every kind of modern day visual including the back of cereal boxes were collaborations with director Luis Bunuel; this duo were out to confront and arouse the bourgeois viewer and the imagery of these two films about desire and obsession are as outlandish today as they were then.

Dali and Bunuel's collaboration left nothing to chance; the letters and notebooks make clear that every image was thought through, every frame storyboarded and worked out. It was during these years that Dali came closest to realizing his vision of wanting film to be a "succession of wonders."

Henry Miller said L'Age D'or "appeal[ed] neither to the intellect nor to the heart; its strikes at the solar plexus, It is like kicking a mad dog in the guts". L'age d'or was anti-romantic, more about thwarted romance than romance, certainly, where the sexiest scene is where the woman is sucking the toes of a statue or trades finger-sucking with her lover. The combination of violence and romance was what got Dali and Bunuel off--they challenged bourgeois viewers in an almost masochistic way. The images are simultaneously horrifying and seductive, perfectly in tune with a guy who was supposedly a virgin when he was married.

By the thirties, Dali had become a household name, appearing in Time and Bazaar, a fashionable, pre-Warhol-ian entity that everybody wanted a piece of, and which, he was only too willing to share. He loved Buster Keaton and Cecil B. DeMiille and Harpo Marx most of all, and came first to Hollywood to visit with him. For Dali, Harpo was the sun and Garbo, the moon. But after Bunuel had gone on to make feature films, Dali's forays into film were less frequent and wrongfooted, most not even getting as far as the cutting room floor.

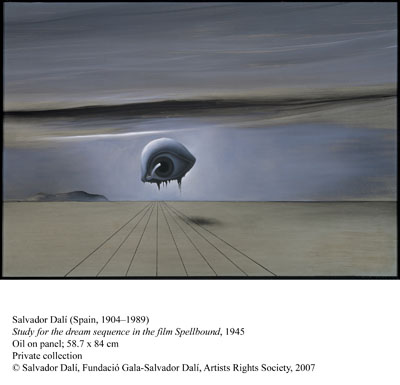

Eventually Dali went on to collaborate with Hitchcock in the dream sequences for Hitchcock's Spellbound and with Walt Disney for Destino, but he was muse and not magician, leaving to his collaborators the real vision. Dali had become shorthand for imagery about the unconscious, (Surrealism by then less a political movement than a visual library of iconic symbols) and about Freud, and Hollywood was eager to tap into it.

When I worked for ABC in NY, one of my assignments was to determine if the David O. Selznick archive (Spellbound only one of many famous films) had any potential to be remade. Selznick had signed Dali on for Spellbound,(under protest; even then he was too expensive), more for pub value than artistic value; I remember thinking, who are they kidding?!: Gregory Peck going crazy a la Dali was sheer noir perfection and I wasn't going to recommend messing with even one frame.

Dali's mostly unrealized work in film in the later years did not stop him from planning out new ventures; he wanted to make a film called The Flesh Wheelbarrow, the "true story of a woman in love with a wheelbarrow...". He wanted people to abandon conventional cinema so that "marvels" could be revealed to them. I can only imagine what he would have thought of the current state of the Hollywood heavens (In the New Yorker last week, David Denby picked up on an old refrain--on how movie stars have lost their magic.)

Though the exhibit focuses on the spillover between the paintings and the cinema, my own antennae led, inevitably, to the connections with the women, or rather woman, who surrounded and looked after Dali for most of his life. About her he once said, "Gala, my wife, is a great exception to every rule, because I find myself married to an authentic rainbow." Gala was a Russian expat who became his muse, his agent, his business manager, and amanuensis, his defensive line against the world. He also thought she was an artistic genius and that only she and he knew the secret to making films without editing--maybe they were prescient about digital!

Do all famous and powerful men need such a person in their lives? It seems so. Men with full plates happily cede problems to the better problem solvers, and Dali was no exception. Gala had already won her Surrealist stripes by being wife and muse to Paul Eluard, the poet and friend of all the great artists of the time. Katherine Conley, a professor at Dartmouth College who has studied these things, claims that this formation, that of muse and lover, model and inspiration, colleague and student prepared the Surrealist women for "positions of prominence in the arts and society [more than]it ever did in oppressing them". Smart and beautiful women were attracted to Surrealism, and to the male Surrealists (Leonora Carrington to Max Ernst, Lee Miller to Man Ray, Dora Maar to Picasso--not a surrealist but similar set up) the way all smart, pretty girls are attracted to revolutionaries: passionate men attract passionate women (and vice versa) no matter how you slice it up.

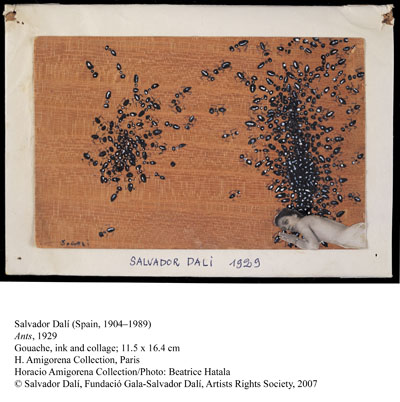

Gala controlled Dali's estate until her death; I'm sorry that I can't post more images from the paintings or the films--a pair of hands against the voluptuous whiteness of a woman's back, the woman sucking the toes of a statue, the hand filled with ants reaching through a door, a woman with her insides showing, one arm tied to a tree branch in a bleak landscape--one thing the Dali estate is still very clever about is tithing handsomely for the reproduction rights to his works. (They are all in the exhibit which travels to the Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida in the winter-spring 08 and next summer to MoMA, or if you can't make it there, in a very comprehensive catalogue published by the Tate.) From the Surrealist whose motives were at first incendiary, Dali has become an industry, one that makes the millions that Damien Hirst is supposedly getting from a consortium for his diamond-encrusted skull or the Murakami show opening at MOCA this weekend, complete with its very own boutique selling handbags, pale by comparison.

No matter. In the end, I think Dali would have felt vindicated that the artistic recognition he sought in Hollywood so long ago had finally been handsomely delivered.