Louise Bourgeois in 1948, courtesy Bourgeois Studio.

Louise Bourgeois, the French-born but American-in-spirit artist died on May 31 at 98. Her giant spider sculptures are everywhere, museum curators having rightly seen in them their simultaneous arachno-grace and arachno-fierceness. Here was a woman whose work and person both expressed this artful duality.

Installation view of Spider Couple, Untitled, and Untitled at Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2008. © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation New York. Photo by David Heald.

Bourgeois was no secret at the end of her life: recognition from fellow artists, a traveling retrospective originating at the Tate Modern in 2007, as well as a keenly observant but unobtrusive documentary by Amei Wallach and Marion Cajori made sure of that. And invitations to Bourgeois's Sunday salons were a coveted perk of being in her inner circle.

But Bourgeois had a rich and productive artistic life before the world--or rather Deborah Wye at the Museum of Modern Art--"discovered" her at the age of 71 and gave her MoMA's first-ever retrospective for a woman in 1982. Further anointed as the US entry into the Venice Biennale of 1993, she later said she had neither sought this recognition nor minded it when it had not come earlier. "It's not me who ignored the market, it's the market who ignored me," she famously claimed, insisting, "the [only] proof of success is whether [a work] says something to me and whether it gives me pleasure".

Bourgeois, whose parents had both been a dominant influence on her in very different ways, left France in 1938 at the age of 27 after meeting and marrying art historian Robert Goldwater. She made her way to the New School in New York to study art.

THE WINGED FIGURE (1948). Collection National Gallery of Art. Photo: Christopher Burke.

FEMME MAISON (1945-47). Private Collection. Photo: Eeva Inkeri.

In between being a painter and then a sculptor after her first NY gallery show in 1945, and along with work on her Femme Maison and Personages series, she did a series called He disappeared into Complete Silence. You might have walked by them quickly at the Guggenheim on the way to the bigger things. But these diminutive architectural drawings and the poignant text she wrote alongside illustrated the possibilities of linking narrative and image and were the things that held me in their spell.

Bourgeois's studio manager Wendy Williams has given me special permission to reproduce this series and share some examples of their haunting qualities with you.

HE DISAPPEARED INTO COMPLETE SILENCE, 1947. Courtesy Cheim & Read, Galerie Karsten Greve and Galerie Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Christopher Burke.

Why are they so affecting?

In 1947, Bourgeois was just an aspiring artist much among the Euro expats (Leger, Duchamp, Modrian et al) who had convened in NY, many of whom had tried their hand at printmaking under the tutelage of New School teacher Stanley Hayter at his Atelier 17. It was here that the sensibilities of the older school Europeans and the younger Americans collided.

Eventually, Bourgeois's outspokenness and her longevity--and faith in herself--combined to make her a formidable, if petite, presence. But the past was omnipresent and the imagery of physical and emotional victimhood was never far away. She never forgot the horror of discovering her father's long term affair with her English governess, or her mother's equally longstanding physical infirmity and forbearance, and the shadows of the disconnect between people. "My childhood never lost mystery, its magic, its drama", she said.

As a poignant aside, Bourgeois says in the documentary that "Francoise Sagan is the sister to me; this is almost my story". She is referring to Bonjour Tristesse, Sagan's novel--the film based on it was recently screened at MoMA-- that tells of the story of the ultra close but twisted relationship--one Bourgeois often portrayed in skeins of rope-- between a daughter and a father. She desperately wanted her father's attention and approval but it was often elsewhere.

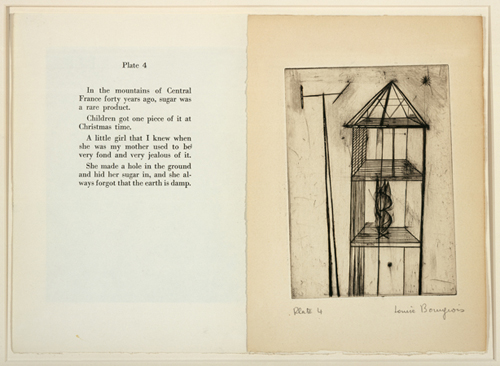

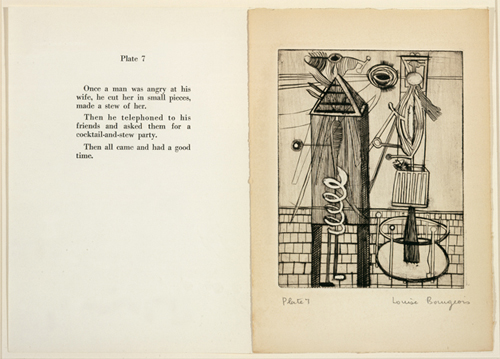

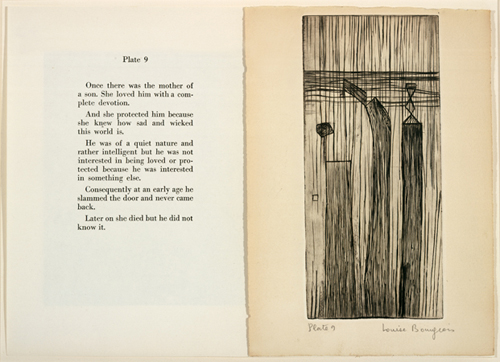

The words and images of the Disappeared series speak to these kinds of disconnects--of the lump of sugar a child hides away in fear , a husband's anger at his wife, a son's disaffection with his mother, disease, a soldier's dysfunctional ear-- like her father, shutting out the world of war.. and her too.

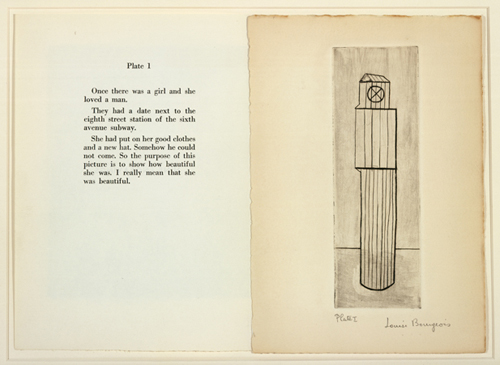

The surrealistic words of Plate 1 are so haunting as to evoke the opening scene of a film.

Once there was a girl and she loved a man. They had a date next to the eighth street station of the sixth avenue subway. She had put on her good clothes and a new hat. Somehow, he could not come. So the purpose of this picture is to show how beautiful she was.

Staying angry about being abandoned was something that fueled her work, and here it's a family of skyscrapers in her beloved New York that gather around her to protect. These nine monochrome prints and texts are loaded with subtext--the truly powerful weapon artists of all kinds have at their disposal. The series of Personage sculptures she made during this period--carved and shaped pieces of balsa wood--were "like another woman's knitting" says her son Jean-Louis. Like the skyscrapers, they are also guardians. Her diaries from that time show her as the busy multi-tasker she was: a hostess, a cook, a good dresser, often the only woman at the table, the non-abstractionist amidst the men who were to take the art world by storm. But the antennae of the spider were growing even then.

I remember going up the Guggenheim ramps and thinking she had achieved this powerfully minimal perfection and finding the larger constructions of real rooms and objects less mysterious and enthralling--as with many artists, having more at her disposal did not necessarily make the art better.

Much has and will be remembered about the original artist: the way she measured herself thumb to forefinger to get the right dimensions for a sculpture's head or the lace collars and cuffs, vests and crisp white shirts, pink fur coats and glittery newsboy caps she favored. She dressed for work at the studio as if she were going to a dinner, the crochet and tapisserie traditions of her family still evident in the obvious thrill she took from textile and intricacy and even the intimacy of undergarments.

Bourgeois became a kind of oracle for other artists, if feared, ("She can be very wounding" confesses Robert Storr in the documentary). A book of her aphorisms was even published, a kind of "Chairman Louise." Here are a few I noted from the documentary in which her male assistant and her son her seen scurrying to her commands and lifting her up like a child in a swing:

Montaigne said Know yourself in order to be happy

What you need and what you get is not the same: the joining of the will and the means

The quality of silence is everything

The runaway girl doesn't function in the family very well

Being in touch with unconsciousness is the artist's gift

Seamstress mistress distress stress (title of work)

She also became a symbol for feminists and taken by them as a totem, like it or not--and none of the first generation of well known creative women did, not Mary McCarthy, nor Lillian Hellman. On the front lines of having made their own way without sisterhood, they were not about to claim it later as the reason they had become successful. They were united by not having been part of the boys club and so to be called one of the girls in solidarity ruffled their hard won feathers. They had spent too much time being tougher, smarter, more ambitious.

The Museum of Modern Art recently convened a symposium (recorded in five parts here) on Art Institutions and Feminist Politics Now. Along with a plethora of concurrent shows of women artists, it seemed as if MoMA was finally allowing the words feminist and artist back into the same sentence, a concept in eclipse these last decades as more and more women artists have sought to define themselves not as women artists but as artists pure and simple.

Yet despite her disclaimers, Bourgeois understood that both she and her sources of inspiration drew from the female wellspring: "the spiders are my most successful subject," she acknowledged, "they must carry a message. The spider is my mother, I try to imitate her, I try to be as smart as she was."

MAMAN (1999) installed at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg in 2001. Private Collection, courtesy Cheim & Read. Photo: Andrea Stappert.