How are we going to live in the rest of the 21st century and beyond?

It's a big question, one that is becoming ever more urgent as resources diminish with few answers from our largely dysfunctional government which has repeatedly refused to grapple with a sound energy policy on every possible level: carbon, oil, jalapenos.

While it sounds like a grocery list, it is, alas, what is pressuring our lives.

So how do we make choices given the absence of leadership? What can WE do that does not depend solely on federal initiative?

Tough questions abound and demand brilliant solutions. While our elected officials dither with each other and the change we need is constantly back burnered, some gifted and original architects have been thinking more radically, ready to propose sweeping solutions to some of our most pressing problems. Do you want to continue to live in a city where most energy consumption takes place? It's cheaper to get around without a car, but that apartment building you live in with all the elevators and the security lights and plumbing is expensive to run.

Or do you want to continue to follow the model of your parents and leave the inner city for the suburbs where your gas guzzling car is just killing your monthly nut but you have a backyard for you and your dog or you and your kids and lots of privacy and a green thing or two to brighten your day?

This preoccupation with Spaceship Earth is not new, as three fascinating companion museum exhibits at the Whitney, the Museum of Modern Art and the Hammer Museum prove.

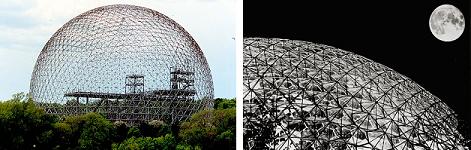

This is how Spaceship Earth looks from up there:

Buckminster Fuller did not think small; Starting with the universe shows how Fuller's preoccupations with Spaceship Earth (his space-age crazy nomenclature), which he shares with Al Gore, with his quest to benefit the largest segment of humanity while consuming the fewest resources, is still unfulfilled. Fuller's genius was to identify and name, no small thing; he was ahead of his time, and, as the exhibition meticulously details, our time too.

or an origami dome.

He wanted us to live together, get together, be together and he was an optimist too: he thought we would be taking better care of each other and the earth by 1985 and that political parties would have disappeared by 2000 (!) We are alas, very far behind his ambitious timetable.

Fuller made a chart of his own time and his place in it called The Grand Strategy of World Problem Solving and it is at once a masterpiece of ego and diffidence. One of his last entries says " I seem to be a verb"! Yet he had to fight his way back from severe, suicidal depression after the death of his first daughter when she was very small and chose instead to dedicate his life to making things better.

Here's some other examples of how Fuller thought:

Everyone is born a genius, but the process of living de-geniuses them.If humanity does not opt for integrity we are through completely. It is absolutely touch and go. Each one of us could make the difference.

Let architects sing of aesthetics that bring Rich clients in hordes to their knees; Just give me a home, in a great circle dome, where stresses and strains are at ease. (a songsmith too!)There is one outstanding important fact regarding spaceship earth, and that is that no instruction book came with it.

We are not going to be able to operate our Spaceship Earth successfully nor for much longer unless we see it as a whole spaceship and our fate as common. It has to be everybody or nobody.

Fuller had his detractors (lots of other architects, I think they were jealous!) and his adherents (Stewart Brand, Whole Earth Catalogue Guru). But his insistence on the fact that responsibility rested with us was prescient. Just think what might have happened if Walter O'Malley had got the land he wanted in Brooklyn to build a Fuller-domed Dodger stadium?

Fuller's Dymaxion House is the link to the two other museum exhbitions. Conceived as an "energetic environment valve with wind powered ventilation and power", using the latest technology from airplanes and boats, combined with, "how nature builds", the house was designed to resist natural disasters, be industrially produced and to combat drudgery, (Here's where the housewives cut a break: three minute laundry, doors that opened with a wave of the hands, children who wouldn't get hurt if they fell on the floor) .

Though the urgency he felt about homelessness and poverty weren't as apparent here as in some later work (Harlem, floating and flying Geodisic cities), the seeds of his "one-town world" burst into full bloom at the Museum of Modern Art in Home Delivery: Fabricating the Modern Dwelling where a look back at prefabs as well as some current models spills over into the parking lot on 54th street (a truly spectacular backdrop).

Steve Kieran of Kieran Timberlake, authors of the Cellophane House, a five-story translucent wonder, tells of the Keystone Cops quality of having to build a five-story prefab prototype out of completely precast materials in the space of two weeks with all the rigorous restrictions of building in NYC. The building is 100 % recyclable though they plan to auction off this house once the show is down so someone will have a chance to actually live with that gorgeous, see-through stairway to heaven they have made inside. (Disclosure: husband's firm is working with them on new projects at UCLA and Singapore)

Nicolai Ourosoff said about the Cellophane House in his review in the NY Times that ,"Hope rises again that we're finally learning to navigate between heroism and hubris"

Mostly known for his futuristic looking Chemosphere, a "hybrid of a flying saucer and mushroom" which directly lifts off from Fuller's Dymaxion House and for his groovy roadside restaurants and for the films that were shot in his houses, the deeper, more versatile John Lautner is the subject of a serious retrospective (the Getty now has his archive) at the Hammer Museum in LA . Beautifully installed, almost as if you were in a studio, or study archive, the curators have decided to let Lautner's visions speak more or less for themselves.

Lautner was a man much less comfortable in his own skin than Fuller, who didn't like where he lived, (LA, "the city un-beautiful par excellence") even though his designs represented the future to Hollywood filmmakers; he found the going Between Heaven and Earth a lot rougher.

The Hammer has made a wise choice in its portrayal of Lautner, mostly working against the groovy reputation he had acquired from the roadside restaurants and movies, instead focusing on him as an iconoclast and a bit of a curmudgeon too, (though he married his partner's wife and then the nurse of his wife proving that architects like to keep it close to home in many ways).

Though the Hammer is also doing a wonderful film program, my favorite is the upcoming symposium on Bachelor Pads and Sex Machines (This is what people mean when they tell me they love architecture. They really mean they love architects.)

Lautner was not known as an environmentalist, but through four big style shifts he tried on new ideas that depended on his own fashion, not others. Though he was deeply influenced at the outset by Frank Lloyd Wright, Lautner was worried about having only one good idea and doing it to death. LA gave him the chance to develop houses on hillsides, from the ground up and he went against the prevailing modernist ethic of Schindler, Neutra and the Case Study Houses that were considered truly innovative.

But even forward thinking architects have to battle against perception. Now that some LEED buildings are actually getting built, the advertising world has decided green is already over. Is it possible that our whole important thrust towards a better way of life will be looked on as a fad like hula hoops?

But if the advertising gurus be damned and prefabs already seem overbuilt and you are determined to go even lower profile

here are some options. (I personally like a shower and comfy bed at the end of hike--more like the Micro Compact Home at MoMA which resembles my stepson's Westie!)

It's worth examining your days and nights, be they bachelor or nuclear family, urban or suburban, whether you are assessing your carbon footprint or not. These architects want us to minimize our need for possessions, to reconcile our need for individuality v. efficient mass production, to try not to have to build that McMansion. What more timely exhibition during mortgage freefall?

But let's not end up with the mentality of the fifties and early sixties, where going underground seemed like the only rational solution.

As Fuller, Lautner and Kieran Timberlake show, by letting architects fool around, we will all get to play in the sandbox with them. And maybe if we follow their lead, our children will get to also.