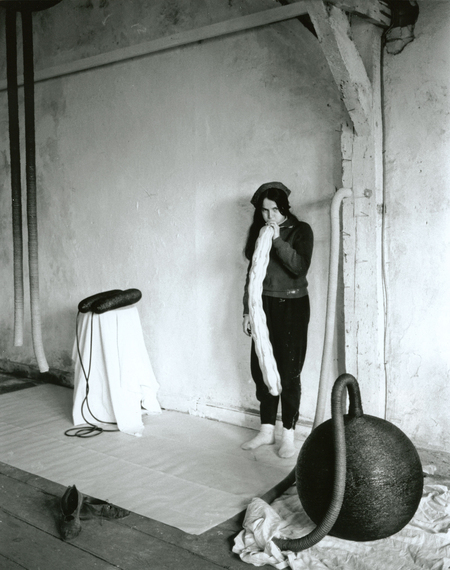

Photo by Barbara Brown

Eva Hesse had a short but intense -- and intensely productive -- life.

An artist who began with one dimensional drawings and paintings but who moved through two dimensional wall hangings and then eventually to room sized sculptures, Hesse was a passionate, tormented, prolific, lovely woman whose reputation has only grown over the years. A new film by Marcie Begleiter and corresponding release of Hesse's diaries adds measurably to the archive.

Like other artists who die well before their time, (at 34, of a series of brain tumors), there is a bit of mystery and sadness about her which only adds to the legend.

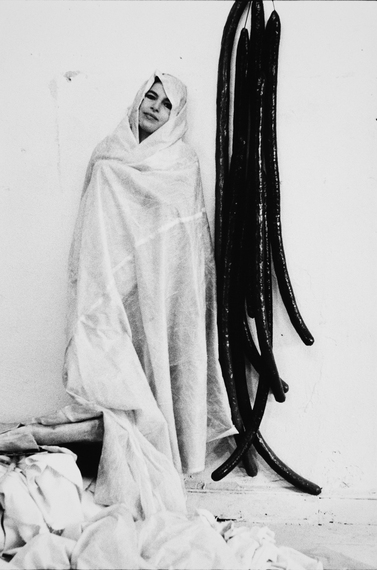

Photo by Gretchen Lambert

Hesse was born in Germany in 1936. The Nazis were already in full throttle, but her relatively prosperous family (father was a lawyer) was able to get her and her older sister Helen out on a Kindertransport to Amsterdam where she lived in a Catholic Home. Her parents eventually joined her and they escaped to New York. The rest of the family perished in concentration camps.

Hesse's father was able to make the adjustment and was Eva's rock, though he did not always understand her work and life choices. The marriage fell apart and Eva's mother jumped to her death when Eva was ten.

The two searing experiences combined to give her a lifelong fear of abandonment and self-doubt. Despite and probably in part because of these tragedies, she was able to devote herself to her work which became everything to her and both stimulated and consoled her when her personal life was in something of a freefall. She felt pretty on the outside, but not on the inside.

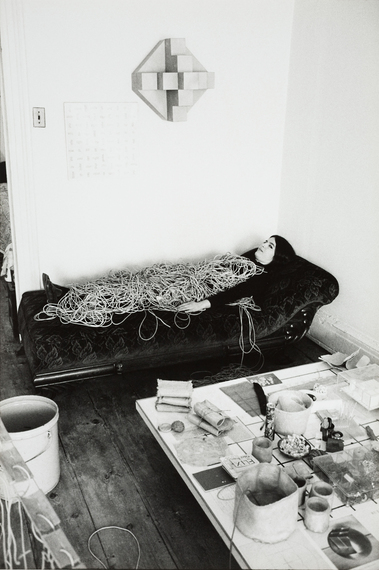

Photo by Herman Landshoff

"There's not been one normal thing in my life", she says (via a wrongly-cast Selma Blair voice-over) at the beginning of the film (Hesse had a New York Jewish accent which we hear in the later audiotapes), "I am willing to walk on the edge."

Hesse with Albers at Yale, 1958

Hesse kept diaries, wrote long letters and talked with artists and interviewers and was apparently vain, so the record of her innermost secrets and her work progression is happily well-documented in photographs and print. She cycled through Yale (a student of Josef Albers), Pratt (dropped out), Cooper Union (loved), Canal Street (her art supply store of choice) and a productive stay in Germany with her husband, sculptor Tom Doyle, (in her fashionable beehive hairdo and peasant shirts) that helped her break through to three dimensions.

Doyle converted to Judaism to be respectful to her father's wishes, but Doyle's hard drinking, flirtatious persona eventually cleaved them. She had relationships with her studio assistant, with other artists and was universally admired. It was the heart of the '60s when freedom and space gave lower Manhattan and the art world its burgeoning power. Sol Le Witt, an extremely close friend, supporter, coach, told her to quit the self-doubt and "DO."

Photo by Norman Goldman

She was a maximal minimalist, a wizard of rope and resin that made her distinctly more "feminine" work contrast with the severity of her fellow artists like Serra, Judd, Graham and Le Witt. Like all the other female artists and writers of the pre-feminist days who came up by her own sandal-straps, she did not want to be known as a woman artist. But it's impossible not to see female imagery in the work.

Photo by Herman Landshoff

The last five years of her life were extremely productive, even when she was in and out of the hospital as a 1972 retrospective two years after her death at the Guggenheim proved.

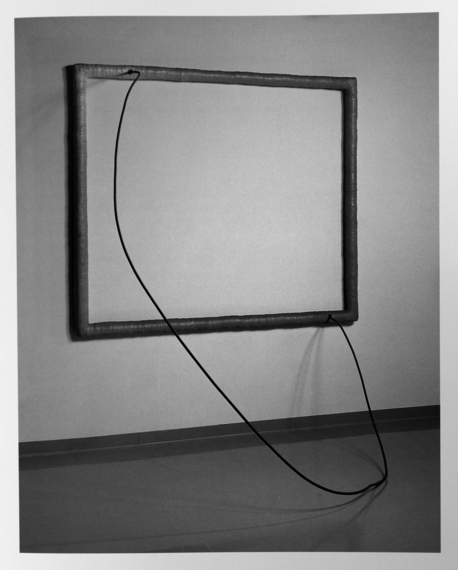

Hang Up 1966 Courtesy of the Estate of Eva Hesse

I am not a huge fan of all the work alas, but that is my own predilection for "more."

Rope Piece with Shadows (Untitled), 1970

I do love a series of circle works on paper that show off her propensity for squares and filaments without the scale of the later works, and some resin sculpture, and the in between years when she wasn't as sure of herself or indeed where her work was going. The film is quiet and understated which serves its more passionate subject well and it joins other recent looks at the women artists and writers of the period which are giving us a reinvigorated, sexually political view of the history of art and literature that is entirely welcome.

"Life doesn't last. Art doesn't last. It doesn't matter," she says at the end. No -- as her life and work prove, both matter very, very much.

Eva Hesse opens today at the Film Forum, New York. All photos courtesy Film Forum and Zeitgeist films