"You said to me: 'I love you.' I said to you: 'Wait.' I was going to say: 'Take me.' You said to me: 'Go away.'"

A woman's voice -- urgent, husky and siren-like all at once -- is heard over a black screen. Suddenly cheerful music reveals a gay turn-of-the-century world. The wild mood swings of the first minute of Jules and Jim, Francois Truffaut's beloved New Wave creation hint at the complex tale about to unfold. The film, which has its 50th anniversary today, is as much a celebration of the unconventional love story as it is of film itself: the romantic pull of its triangle was matched with pure filmmaking panache, a valentine to love and friendship in all their complicated messiness.  Oskar Werner as Jules (r), Jeanne Moreau as Catherine (c) and Henri Serre as Jim (l); Credit: Jules and Jim, Courtesy of the Criterion Collection

Oskar Werner as Jules (r), Jeanne Moreau as Catherine (c) and Henri Serre as Jim (l); Credit: Jules and Jim, Courtesy of the Criterion Collection

I first saw Jules and Jim at the Cinematheque in Paris where vintage films were shown strictly uncut and undubbed as their directors, or auteurs, originally envisioned them. I was in flight from my previous alt-selves -- sorority girl, political activist, rock and roller -- on a semester abroad. For two francs -- then around 20 cents -- I studied the New Wave cinema heroines, none more intriguing than Truffaut's Catherine, the earthy, pouty-lipped enigma who knew how to keep two men dangling simultaneously, hoping for clues to my own version original. Why, in Paris, even your knee had possibilities. (Eric Rohmer's Claire's Knee).

Truffaut called his film Jules and Jim after a novel he had fallen in love with which followed the volatile friendship of the men over the course of two decades, but I entered it through the portal of Catherine, who was its dangerous spark. It was Catherine who most drew your attention -- not just because of her sensual beauty but for the simple fact that you never knew what she was going to do next. Catherine was a modern woman who double-dared her lovers to meet her in a "no-woman's" land where she set the rules. How did Jeanne Moreau, the actress Truffaut said helped inspire him to make the film, infuse so much mystery and charm into the smallest look and gesture?

Oskar Werner as Jules (r), Henri Serre as Jim (c), and Jeanne Moreau as Catherine (l); Credit: Jules and Jim, Courtesy of the Criterion Collection

Oskar Werner as Jules (r), Henri Serre as Jim (c), and Jeanne Moreau as Catherine (l); Credit: Jules and Jim, Courtesy of the Criterion Collection

Catherine and Patricia (from Jean-Luc Godard's Breathless) film-ended my stay in Paris -- one the essential Frenchwoman, the other the essential American girl (Truffaut had actually come up with the story for Breathless and given it to Godard). Truffaut and Godard believed that women could be powerful, independent and the object of grand desire, for whom men were willing to check their own needs at the door. But both heroines suffered from a malaise that also stalked me at the time: the fear of being shut inside a relationship and thus deprived of the possibilities of the rest of life.

Catherine was a new kind of femme fatale, not a blatant sex kitten like La Bardot, but one who could get away with wearing men's clothes and painting a mustache on her face and still be intensely feminine and sexually provocative. Like the character she admires in a play, she invents her life at every moment.

Perhaps, I fantasized along with thousands of other young women, by cutting bangs, wearing a rakish newsboy cap or a wide headband and an oversized boyfriend sweater I would somehow be infused with the essence of Catherine and could learn how to be in charge of my own destiny.

We learn the story of Jules, Jim and Catherine in the grisaille of grainy black and white still unmatched for its allure. The two men, writers, meet over the search for a costume. They bond over poetry and art, indifference to money, and especially over their love for women. Wrapped up in conversation with each other, they reclaim the possibilities of male friendship, as deep and engaging as that of any female BFFs. Catherine enters their life as a friend of a cousin of Jules (Oscar Werner), the German. It all begins playfully enough as the trio retreat to the sea and share other adventures. Jules adores her, and she marries him, but soon, Catherine's need for both men's undivided attention bubbles up. If they play cards, or talk late into the night, or in any way ignore her, she creates a disturbance -- jumping into the water, dressing up like a man, or playing tag. The thing is: she is never "it" but always the object of the chase. Jim (Henri Soule) wins her for a time, but it cannot last. Over the course of two decades until the eve of World War II, Catherine moves in and out of their affections -- and ours -- without regard for consequences. How did she get away with it, I asked myself? Truffaut didn't want the public to judge his characters but to show that sometimes, nobody is right. Still, at times Catherine seems horribly callous, playing with their affection for her.

Jeanne Moreau as Catherine and Henri Serre as Jim; Credit: Jules and Jim, Courtesy of the Criterion Collection

Jeanne Moreau as Catherine and Henri Serre as Jim; Credit: Jules and Jim, Courtesy of the Criterion Collection

"Man never owns anything for a very long time," Moreau later said in a remarkably candid Film Comment interview. "You lose everything, good and bad. If you have something that makes you happy, you'll lose it. If something happens to you that's painful, it won't last either."

A cache of letters released by the French Cinematheque from the book's author Henri Pierre Roche to Truffaut as well as annotated text including scripts, outlines, treatments, production images and video segments makes plain that just about everything in the long gestation of Jules and Jim was meticulously planned. The visually exciting archive shows Jeanne Moreau to be every inch the seductive actress and documents how much she, the novelist Roche, the screenwriter Jean Gruault, and the cinematographer Raoul Coutard were emotionally invested in the project and Truffaut's vision.

Truffaut, barely 30 when the film was released, describes a coup de foudre he had upon discovering the novel in a second hand shop, a thinly veiled story of Roche's relationship with a German couple, Helen and Franz Hessel, who had left a profound mark on the life of this renaissance-man/collector/artist/writer. He seems to also have fallen for Moreau, tracking her career and staying in regular touch with her for this and other projects.

Moreau -- who once told an interviewer sleeping with people was one of the best ways to get to know them -- was already recognized for her work in the theater and had played perfidious wives in Elevator to the Gallows and Les Amants (both films directed by Louis Malle with whom she was involved). After meeting Truffaut with Malle at Cannes, actor Jean Claude Brialy brought Moreau to the set of The 400 Hundred Blows as a surprise since he knew Truffaut admired her. Truffaut gave her a spontaneous walk-on in the film and gave her the Jules and Jim novel soon after for her reaction. She merely answered, "When do you wish to begin," becoming the project's muse.

"She gave me courage each time I was overwhelmed by doubt," said Truffaut. "Her qualities as an actress and a woman made Catherine real in our eyes, plausible, crazy, abusive, passionate, but above all loveable, in other words, worthy of adoration."

When she's not busy being a goddess, Catherine can be like like a willful child who uses sex and love instead of tantrums to test limits. Early on, Jules claims a woman's fidelity is the most important thing in any relationship. She reassures him after they marry that since she is very experienced with men and Jules less so with women, they will "cancel each other out." Yet later he gives her the freedom to do whatever she wishes as long as she stays in range; he can't bear the thought of her going away forever.

Jules: She is a force of nature, she expresses herself in cataclysms. Wherever she is, she lives surrounded by her own brightness and harmony, guided by the conviction of her own innocence.

Jim: You talk of her as if she were a queen.

Jules: But she is a queen. Catherine is neither particularly beautiful nor intelligent nor sincere but she is a real woman and she is woman we love and whom all men desire...

Jeanne Moreau as Catherine; Credit: Jules and Jim, Courtesy of the Criterion Collection

Jeanne Moreau as Catherine; Credit: Jules and Jim, Courtesy of the Criterion Collection

Catherine has one child with Jules but wants another with Jim, something to anchor anew her restless spirit. Despite all this, Truffaut makes it believable: that two smart men would give over to this "force of nature" and tiptoe around her and try to accommodate her every wish because of their love and reverence for her as a wellspring of creativity -- and because they are petrified that something disastrous will happen.

Which it inevitably does.

Finally her testing the limits goes to its extreme and she invites Jim into her car and drives them off the bridge (supposedly the inspiration for Thelma and Louise's iconic ending). Truffaut and the other directors of the New Wave were determined to move the needle away from the conventions of the 50s and gave their female characters the torch of independence, experimentation -- and a certain selfishness too -- to carry. He understood: these women were "easy to get, but hard to keep." I was not yet a wife or mother when I saw the film and so its message was particularly seductive.

Moreau told Film Comment, "Through me, Francois learned about women and through him I learned about cinema." Truffaut's instinct for great female characters was unerring, but he later ran from the rigid categorizations of the early feminists, "the way things are now would more likely make me want to chuck it all."

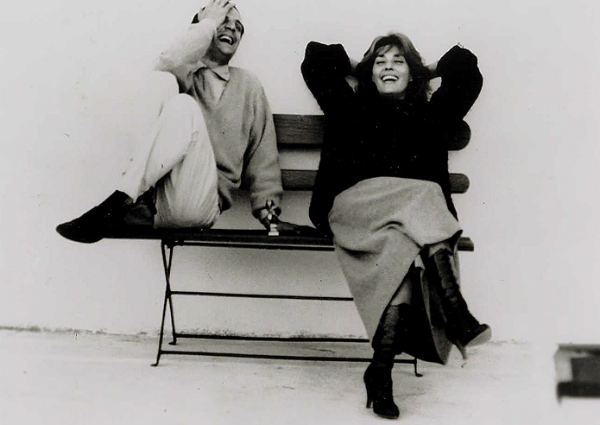

Francois Truffaut and Jeanne Moreau; Photo copyright Raymond Cauchetier, courtesy of the photographer

Francois Truffaut and Jeanne Moreau; Photo copyright Raymond Cauchetier, courtesy of the photographer

I sought out Jeanne Moreau, whose 84th birthday is also today, for a recent comment about the film, but she demurred.

She wrote me, "I am very sorry but I am working on three projects and my mind is not going back to the past."

In the Film Comment interview, however, when she was trying to separate out her career from the famous auteur for whom she had been a muse and make her own way as a director -- she was less reticent.

"When I made Jules and Jim, said Moreau: "I was at that age where one lives very egocentrically; I saw it as the chance of a lifetime a chance to escape the 'star' style... all of a sudden we were filming in the street with very little makeup, costumes you found yourself. No one was telling me anymore, "You have circles under your eyes, your face is lopsided" -- suddenly it was life. And I felt that if I was going to thrive and have fun working in front of the camera, it would be like this."

Francois Truffaut and Jeanne Moreau; Photo copyright Raymond Cauchetier, courtesy of the photographer

Francois Truffaut and Jeanne Moreau; Photo copyright Raymond Cauchetier, courtesy of the photographer

Moreau said that the communication between herself and Truffaut "was very intimate, but we didn't use words."

"Real directors don't try to influence you," she claimed, "but allow you to flourish."

Raymond Cauchetier, now 92, the talented on-set photographer of many of the most important New Wave films whose name is regrettably less known, captured this intimacy in these previously unpublished photographs. An exhibition of his iconic images will appear in Los Angeles in March at the Motion Picture Academy.

Francois Truffaut and Jeanne Moreau; Photo copyright Raymond Cauchetier, courtesy of the photographer

Francois Truffaut and Jeanne Moreau; Photo copyright Raymond Cauchetier, courtesy of the photographer

Catherine and Patricia and the other New Wave heroines lingered in my imagination. One of my very first assignments at The New York Film Festival was to pick Truffaut up at the airport with my mentor -- and best friend -- from the office. We wore pleated mini skirts, remembering that in La Peau Douce, one of Truffaut's earliest films, Nicole (Francoise Dorelac, Catherine Deneuve's younger sister who died tragically young in a car accident) changes into a skirt when her lover Pierre tells her he prefers them. We primped and giggled all the way out to JFK in the back of the limo, but the prospect of Truffaut's discerning eye on me made me both nervous and hopeful: would he be able to tell if one day I could be a force of nature too?

At one point when the men who love her are thrust together again, Catherine sings a song -- "Le Tourbillion de la Vie" -- to the assembled hopefuls, each of whom hangs on her every word.

"We escaped from each other, We lost each other, We found each other again, It's the whirlwind of life."

I sing this song to myself when I want to remember too, the no-holds-barred spirit of Jules and Jim and Catherine that once propelled me forward into life.

The marvelous double disk set from Criterion is a worthy investment for those who wish to discover or rediscover the film. The extraordinary Zoom on the film on the website of the Cinematheque Francaise, is a gift for those who can read French; this site is the most elegant and informative website of ANY I have consulted; the book by Henri Pierre Roche is available on Amazon; Two in the Wave, a touching documentary about Truffaut and Godard is now streaming on Netflix. Raymond Cauchetier's more recent work is discussed in this article (also in French). My own story about Breathless and Godard appears here on the Huffington Post.