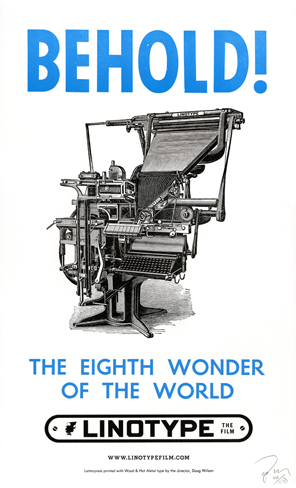

The famous inventor Thomas Edison called the Linotype the "eighth wonder of the world." So what precisely is it? A typesetting machine that sets one line of type at a time, is the simple answer. But its also an invention that revolutionized the world -- yet most people have never heard of it, or creator Otto Mergenthaler.

Doug Wilson's film is a fascinating tribute to an invention that heralded the dawn of mechanical typesetting and played a pivotal role in the advancement of print and publishing. Introduced in the late 1800s, it rapidly replaced the art of setting metal letters by hand with a new set of skills -- operating a Linotype machine. Mergenthaler was a German watchmaker and inventor who came to America in 1872. He settled in Baltimore, where he was asked to find a quicker way of publishing legal documents. His idea was a machine that would both stamp the letters and also cast them. It resembled a giant typewriter -- the operator entered text on a keyboard, and then cast a single piece, called a "slug," of type metal. This process became universally known as "hot metal typesetting."

Along with letterpress printing, it became the industry standard for all forms of print, including books and posters. The New York Times was set using the Linotype for 80 years. After a lifetime of service its reign eventually came to an end with the arrival of the Photosetter in the '60s and '70s. This in turn was replaced by the digital technology that we now use today.

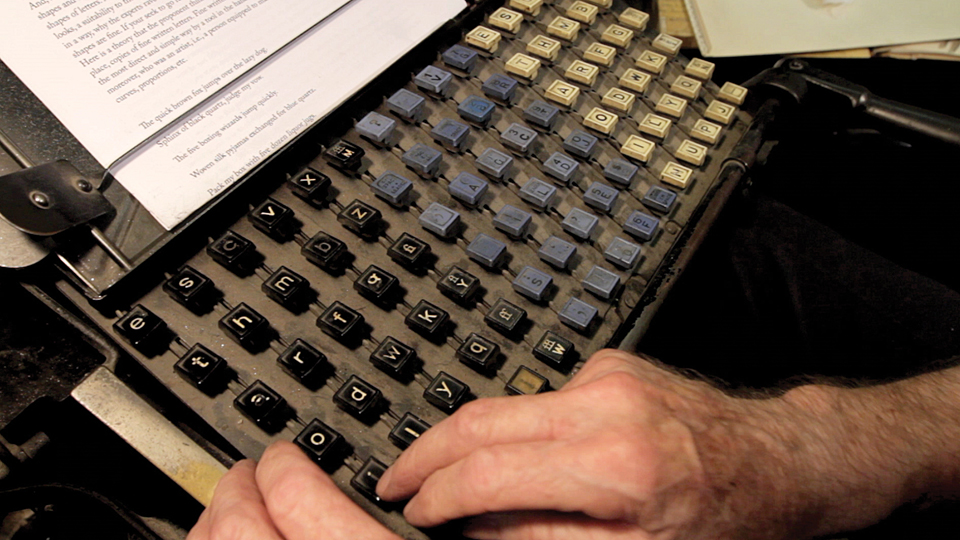

Wilson brings this history to life via the stories of some of the last of the original operators, as well as some wonderfully eccentric modern-day enthusiasts -- the film is full of charming anecdotes and amusing sound bites. It took a particular kind of person to actually operate the machine, which not only required tuition and craftsmanship, but a degree of fearlessness as these contraptions would from time to time squirt out molten metal. And there was the noise. One of the reasons that newspapers of the time liked to employ deaf people was because they were not bothered by the din of working conditions. One such operator was Eldon Meeks, now 83, who demonstrated the skill that still makes him the fastest known Linotype operator today. Despite not being able to hear the machines, operators such as Meeks could otherwise sense when something was going wrong and respond to it as quickly as anyone else.

The Linotype has a unique 90-key keyboard.

Described in one scene as being like a ballet between man and machine, the relationship turned for some into a kind of love affair. When its role as the universal way of working came to an end, many were heartbroken -- not just as there own skills became redundant, but also to see their long-serving workhorses literally thrown out as scrap metal. Some survive in museums and personal collections, but keeping them in working order is time-consuming and expensive. One owner in particular finally decides to consign his to the scrap yard, but struggles to look on as his film is being demolished.

The letterpress survives as a specialist practice, and there are passionate younger enthusiasts in the film learning the craft of using the Linotype. But whether this knowledge will be passed on to future generations who keep the art alive or if it will only survive as museum exhibits remains to be seen. The documentary is sensitively filmed and edited, not just an important record of a significant chapter in print history, but a testament to the people who understood and worked every day on these extraordinary machines.

All images: © Linotype: The Film

First published in Crafts magazine, July/August 2012