One hundred years ago in New York the great Grand Central Terminal was inaugurated as a world gateway. It stands today as the city's only remaining humane and inspiring entry point. Over the last generation after real estate developers were defeated in court by community activists led by Jacqueline Onassis in their effort to destroy it, the station has emerged as an ennobling gathering place whose architecture literally lifts the attendant soul. This is the power of public place making at its exemplary best.

Meanwhile, fifty years ago brought the opposite fate to its crosstown cousin: the demolition of the late great classical temple of Pennsylvania Station, replaced as it was by the rat infested basement of Madison Square Garden alongside twin commercial towers of a soul-deadening banality that is second to none in America today. Its demise helped spawn the overall landmarks preservation movement in America which not only saved Grand Central but set a standard of community engagement in the shaping of cities. It was a new voice for the voiceless finally appreciating their collective power in defiance of the elected and appointed officials cowering in sanctioned compliance with the most powerful developers, whose capacity to get whatever they willed was at the very least challenged by a new mechanism of citizen engagement.

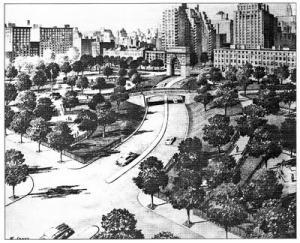

The maw of top-down urban renewal with its wholesale condemnation of entire neighborhoods (as opposed to new construction within existing urban fabric) upon which strong communities rely at last began to break down. Green space became sacred, with every square inch coveted in the face of the evident impossibility of ever replacing it amidst such development pressure and overzealous bureaucrats like Robert Moses, who never saw a park he didn't want to pave over in some manner. For him Washington Square Park, where bohemian Greenwich Village gathered both to protest and celebrate, seemed above all an ideal right of way for a broad extension of Fifth Avenue to facilitate traffic flow and allow an off ramp for his hoped-for cross-Village sunken superhighway.

The "Arab Spring" which has now turned two has unfolded unevenly for myriad reasons of which just one is the access to and meaning of place where energy could gather and events unfold. A cross-cultural impulse comparable to the American preservation movement safeguarding spatial connections has thus emerged along with greater personal freedom. Cairo's Tahrir was the supreme case in point like the Mall in Washington or New York's politics-laden Union Square, or Chicago's Grant Park where protest whether peaceful and violently wiled can provide a locus of democratic will.

In Bahrain meanwhile a relatively meager traffic circle called the Pearl Roundabout proved barely adequate as necessary focal point for organized Arab Spring protest. Even so, an oppressive minority ruling elite demolished it entirely in bloody suppression of street-driven dissent. A public square was literally eliminated and rendered the antagonists invisible at least for the short term.

Tahrir Square was too large, important, and historic for even an oppressor to dismantle, at least once the collective forces demanding change had lodged there; in Bahrain it was the opposite and the results unfolded accordingly. Tahrir was the Athenian Agora or the Roman Forum; Pearl Roundabout a displaced blueprint for a murderous stockade.

Such lessons of public identification with place and the landmarks of historic continuum and civic pride are not lost on an increasingly authoritarian anti-modern and theocratic Turkish regime, whose powerful prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, imposes his will in the opposite mold of the Republic's secularist founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. The methodical destruction of historic Taksim as precious green space and crossroads of youth, commerce, and international encounter is a tactical pathway towards a strategy of control. For a latent oppressor its parades and celebrations are a terrifying harbinger of prospective disobedience. The attachment to place requires severing it through wholesale demolition.

Like New York's joyously crowded Grand Central and the Arab world's historic squares, Taksim is a public space that in the minds of nascent autocrats risks not merely to accommodate unrest but actually to kindle it. And so in self-fulfilling prophecy their destruction of beloved trees and lawn amidst such colossal density and dirt has done exactly that. And their final intent of control literally laid bare.

Coming weeks will reveal the great stresses for which Taksim is merely a symbolic fuse, yet should remind all regardless of home of the essential social wellbeing of enduring public places that bind citizens in shared values in times both of strife and days of joy.

As Taksim goes, so may go the modern Turkish experiment as a vital bridge between America, Europe, and the Middle East. From transportation hub to the public square, these are vivid examples of the power of place and the bonds of culture they provide. The user public must never take them for granted as Americans learned with the rise of preservation.