"Man is by nature a social animal ... Society is something that precedes the individual. Anyone who either cannot lead the common life or is so self-sufficient as not to need to, and therefore does not partake of society, is either a beast or a god." -- Aristotle

We all know that certain behaviors increase our risk for disease and premature death. Doctors routinely inquire about smoking, alcohol, diet, sleep, and more recently inactivity. Something you probably haven't been asked at your annual checkup is, "Are you lonely?"

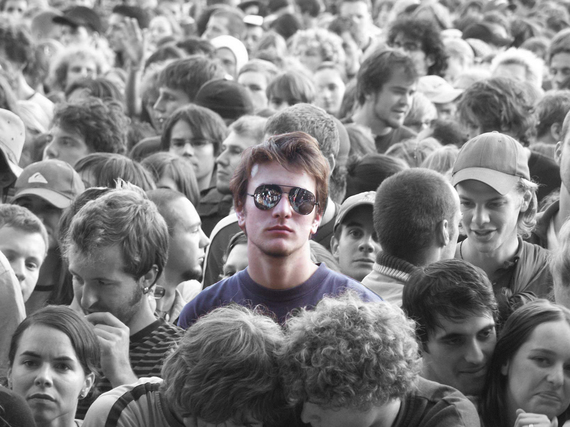

A growing body of research indicates that social isolation is becoming more prevalent and can wreak havoc on our health. It is comparable to hypertension, smoking or alcoholic drinking and exceeds the influence of inactivity and obesity. Social connection appears to protect us from cardiovascular disease, depression and hypertension, ward off dementia, raise IQ and increase our chances of surviving cancer.

Why would social ties have such a profound effect on our health?

Growing interest in this question has created a voluminous body of fascinating data and a new field: social genomics.

Three important observations merit mention at the outset.

1. Perceived social isolation (loneliness), not objective social isolation, is the more important determinant of health effects. The quality of relationships, rather than the quantity, dictates the experience of loneliness.

2. Because the stress response is one of the most conserved phenomena in evolution, the biological effects of perceived social isolation in humans is similar to those observed in animals when isolated experimentally. It triggers a stress response with increased sympathetic tone (fight or flight response), increased inflammation, impaired immune function, sleep disruption and increased expression of genes regulating stress hormones.

3. Our genetic self is not fixed. Gene expression is responsive to our environment, including our social world. This plays out in real time, hour by hour. This is revolutionary. Changes occur in gene activity and lead to modifications that can be transmitted to daughter cells. The process occurs through a modification of the material surrounding the genes by agents such as hormones, radioactivity, viruses, bacteria, basic nutrients, pollutants and social experiences such as secure attachment or rejection. These modifications turn the affected gene on or off and are critical in explaining how environmental factors can have such profound, long-lasting influence on both physiology and behavior. It is the intersection of nature and nurture.

Like other social species, humans could not have survived without banding together and living as a group. Separation from the group was a death sentence. A self, apart from the clan, was unimaginable until relatively recently in our history. In addition, even amongst social species, humans are unique in their extraordinarily long period of total dependence after birth.

Recent research suggests that the pain of social isolation, loneliness, evolved as an alarm signal. The brain surveys our environment to assess potential danger, both physical and social. Diminishing social connectedness threatens survival. Feelings of loneliness signal the need to restore relationships in order to remain attached to the group.

In the same way physical pain evolved as a signal to protect the body, the pain of social disconnection triggers discomfort to protect the social body. In fact, experiments have demonstrated that social rejection activates the same neural pathways as those involved in the experience of physical pain.

Many variables have contributed to the growing population of lonely individuals. More than one in four households had just a single person in 2012, greater than at any time in the past century. In 1970, one-person households accounted for just under one in six. In 1900, it was one in 20. Americans are marrying later, having fewer children, divorcing at higher rates and living longer. Most people no longer live with extended family or even nearby.

However, because loneliness is a psychological state determined by the quality of relationships and not by numbers, we must look beyond this data to determine whether or not we are lonelier now than in the past. For instance, marriage has been shown to prevent loneliness if one's spouse is a confidant. Under less intimate circumstances it can be the source of loneliness.

The gold standard of testing for loneliness in the research world is the UCLA Loneliness Scale.

INSTRUCTIONS: Indicate how often each of the statements below is descriptive of you.

Statement Never Rarely Sometimes Often

1. I feel in tune with the people around me 1 2 3 4

2. I lack companionship 1 2 3 4

3. There is no one I can turn to 1 2 3 4

4. I do not feel alone 1 2 3 4

5. I feel part of a group of friends 1 2 3 4

6. I have a lot in common with the people around me 1 2 3 4

7. I am no longer close to anyone 1 2 3 4

8. My interests and ideas are not shared by those around me 1 2 3 4

9. I am an outgoing person 1 2 3 4

10. There arc people I feel close to 1 2 3 4

11. I feel left out 1 2 3 4

12. My social relationships arc superficial 1 2 3 4

13. No one really knows me well 1 2 3 4

14. I feel isolated from others 1 2 3 4

15. I can find companionship when I want it 1 2 3 4

16. There are people who really understand me 1 2 3 4

17. I am unhappy being so withdrawn 1 2 3 4

18. People are around me but not with me 1 2 3 4

19. There are people I can talk to 1 2 3 4

20. There are people I can turn to 1 2 3 4

Scoring:

Items 1, 5, 6, 9, 10, 15, 16, 19, 20 are all reverse scored.

A recent AARP national survey of people 45 and older found that more than a third (35%) were lonely by the UCLA scale, compared to 20% for a similar group a decade ago. This increase in loneliness is all the more noteworthy because it coincides with an internet revolution in our social world. 1.65 billion people are active Facebook users. 4.5 billion likes are generated daily. Like and share buttons are viewed across 10 million websites every day. Every 60 seconds five new profiles are created and 293,000 are updated. One in five page views in the US occurs on Facebook.

We appear to be more connected than ever before. The median number of friends on Facebook is 200. How does this compare to offline social networks of the past?

The social brain hypothesis suggests that there is a natural group size for humans. The limit is defined by a cognitive constraint (the size of a part of our brain, the neocortex) and a time constraint (the cost of servicing relationships). This has been validated with contemporary hunter-gatherer populations and personal offline networks. Friends are grouped in hierarchies of 5, 15, 50, 150, 500 and 1500 members. The outer two layers correspond respectively to acquaintances and faces we can put names to.

Research has found the same hierarchy on and off line. Most importantly, the inner two groups of 5 and 15, sometimes called the support clique and sympathy group, have not expanded with internet socialization. It appears that we can only interact meaningfully with a handful of people at any one time. Each individual distributes her social capital in a personal way that remains stable over time but is numerically constrained whether on or off line.

So the number of friends has not proved meaningful. There is data both for and against blaming the increase in loneliness on the internet. What we do know is that humans are exquisitely vulnerable to social isolation and rejection. Our physical and mental health depend upon real connection. By real I mean a situation in which we feel known, understood, and cared about. We can experience this with a very small number of people at any given time. Quantity cannot make up for the quality of our relationships.

Facebook is not the equivalent of face time. The quality of online relationships are compromised by the absence of face-to-face interaction. Social media lends itself to the presentation of a fictional idealized persona that may appear more desirable but distances us from ourselves and the meaningful contact we all need.