When choosing a doctor, we consider many things; training, experience, age, gender, hospital affiliation, office location, insurance coverage. We rarely think about the doctor's health. A growing body of research suggests that we should. The way your doctor takes care of herself affects how she will take care of you.

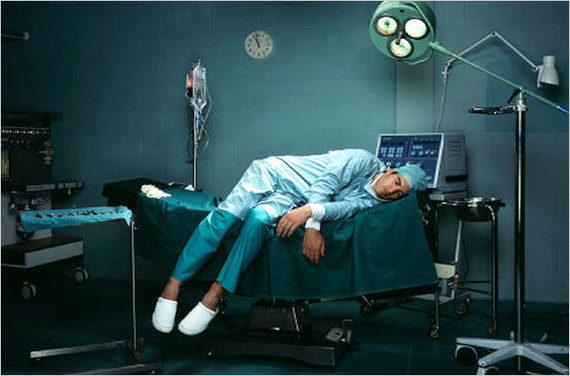

This is not good news given what we are learning about physicians' wellbeing these days. A recent report in the Proceedings of the Mayo Clinic documents an alarming rate of burnout and dissatisfaction with work-life balance in our healers. While these sound like common complaints of modern existence, a burnt out physician is an impaired physician. Burnout here is defined as a syndrome of emotional exhaustion, loss of meaning in work, feelings of ineffectiveness, and a tendency to view people as objects rather than as human beings. This followup study compared 6880 doctors to other US workers. A similar survey was conducted in 2011.

Doctors are known to be a competitive high-achieving group. Unfortunately, in characteristic fashion, they have outstripped other professionals in this arena. The number of physicians experiencing at least one symptom of burnout increased from 45.5 percent in 2011 to 54.4 percent in 2014. Satisfaction with work-life balance also worsened between 2011 and 2014, 48.5 percent vs 40.9 percent.

These trends run counter to the general population. Minimal changes were observed in non-physician workers during these years, thus increasing the disparity between physicians and other US workers. After adjusting for age, sex, hours of work and level of education, the gap remained.

A significant variation in the rate of burnout was observed by specialty and career stage. Specialties on the front line of care (family medicine, general internal medicine and emergency medicine) and physicians in mid-career had the highest prevalence of burnout. In other words, the doctors you're most likely to see are at greatest risk for these problems. That puts you at risk.

Compared to 2011, satisfaction with work life balance (WLB) was lower in 2014 for all specialties except obstetrics, gynecology and general surgery. For the control US worker group, satisfaction with WLB had improved a bit during this period, 61.3 percent vs. 55.1 percent. After adjusting for age, sex, relationship status and hours worked per week, doctors had a risk for burnout that was twice that of the general US population.

The compromised wellbeing of the contemporary physician is reflected in a slew of statistics. They have disproportionately high rates of substance abuse. Of all professions, doctors have the most at fault motor vehicle accidents. Physicians' rate of suicide in certain age groups is six times greater than the general population. As many as 400 physicians kill themselves each year, a number comparable to the graduating classes of two or three medical schools. The list goes on.

The deterioration of wellbeing described in these studies begins earlier than one might suspect. Research indicates that future doctors begin their training with mental health profiles that are on average more robust than those of college graduates pursuing other fields. This picture is reversed within the first two years of medical school.

Numerous studies demonstrate a link between both burnout and depression, and medical errors. Data on residents indicates that over 75 percent meet criteria for burnout. These residents had a two to three fold increased probability of providing suboptimal patient care. Such care includes failure to fully discuss treatment options or answer patient questions, treatment or medication errors that were not due to lack of knowledge or inexperience, and reduced attentiveness or caring behavior towards their patients. Similarly compromised care was observed in the 20 percent of residents who were depressed.

One of the striking observations from this data is an ironic cycle of stress, guilt regarding suboptimal delivery of care, depression/burnout, and a worsening of quality of care. This would suggest that doctors deeply care about giving good care but often fail to live up to their own expectations which results in a deterioration in their mental health that further compromises their performance.

How are we to understand this epidemic?

The dramatic reversal in the mental health of medical students implies that there is something pathogenic about immersion in professional medical culture. Working in this world has always been stressful. But the current picture of depression and burnout is relatively new.

What has changed in medical culture over the past 50 years?

Certain stresses have always plagued medical workers. Daily exposure to people who are suffering, frightened, dying and hoping the doctor will fix things is emotionally draining. Bearing witness to another's trauma (anyone who is significantly ill is traumatized) can traumatize those workers. The syndrome, referred to as vicarious traumatization, empathic strain, secondary victimization, compassion fatigue or burnout, is a kind of post traumatic stress syndrome where the trauma is ongoing.

Two key findings have come out of research in this field. One, If you really listen to what the patient is telling you, it will affect you. And two, the most effective coping strategy is to acknowledge that you are being affected and seek help. Both of these ideas run counter to the ethos of doctor culture.

Doctors believe that they should not get sick. Being sick and seeking care are stigmatized. It suggests weakness and that the doctor is less competent medically. A recent study reflects this climate of denial. 95 percent of hospital physicians reported that working while sick puts patients at risk. However 83 percent of those physicians admitted to going to work while sick. The most common reasons given were, not wanting to let colleagues down (99 percent), not wanting to let patients down (93 percent) and fear of being ostracized by colleagues (64 percent).

Resilience is not taught in medical school. It is expected. To admit a problem is to be weak and less than one's stoic peers. It risks being judged negatively. Despite a biological understanding of mental health, many physicians still believe these disorders are evidence of a lapse of willpower or moral failure when they appear in other physicians. This results in a double loss. Not only do doctors not take proper care of themselves, they often take poor care of each other.

While medical training has not changed dramatically over the past 50 years, the practice of medicine has been transformed. Chronic illness and life-prolonging technologies present unsolvable ethical dilemmas. Reimbursement systems curtail engagement with the patient and dictate practice plans. Direct-to-consumer drug advertising, online doctor ratings, increased monitoring and increased accountability are all recent changes that increase doctors' stress level.

The ever increasing scrutiny and asymmetry of reward and punishment in the setting of decreased autonomy have unbalanced the profession. Human behavior research has shown that as one spends more time and mental energy fearing the consequences of making mistakes, we increase the odds of doing just that; making mistakes. These changes in the medical landscape appear to have brought already stressed physicians to a tipping point. Although implemented to improve quality of care, they have resulted in the opposite.

If we care about our health, we must address physician health. This can only happen with a shift in the culture of care and wellness of doctors. Self-care must become a core competency in medical training. Such radical change requires the involvement of all stakeholders, the doctors, the health policy makers and most importantly, the public.