A kind of Russian mystery one would expect out of Gorky Park is unfolding at the James Gallery on the first floor of the CUNY Graduate Center on Fifth Avenue at 35th Street (in the old B. Altman building) in a show of paintings and installations by Russian-born painter and conceptual artist Yevgeniy Fiks entitled "The Lenin Museum."

I have been avidly following Fiks's career for roughly a year, when I learned of a show he had at the Galerie Sator in Paris called "Homosexuality Is Stalin's Atom Bomb to Destroy America." The quote comes from a 1953 article by Arthur Guy Matthews, a famous American "Cold Warrior" and pundit of the period. The show had previously been at the Winkleman Gallery in Chelsea, but I'd heard nothing about it till I got wind of its Paris offering. The title alone returned me to that stunned feeling you have when the past suddenly opens up and spits poison at you.

I understood the concept behind it completely: I had lived it in fact. Growing up in very conservative Savannah, GA, during the McCarthyist 1950s into the early 1960s (I used to say that the 1950s lasted in Savannah until about 1975), being taken for queer and a Red was automatic: a knee-jerk response. The Queer-Red paint was also used to tar blacks and their white friends and associates during the Civil Rights struggle. The accepted wisdom of the period was that if you were involved with Civil Rights you had to be A) a Red--like Harry Hay, B) queer--like Bayard Rustin, or C) a sexual reprobate--like Martin Luther King.

One seemed to follow the other, as night follows day--or was that the logic to being true to oneself and therefore never being false to any man, as Polonius advises his son Laertes?

In Yvegeniy Fiks's firmament of queer men in the Soviet Union under Stalin, no one is ever true to anyone else. There's too much terror and threat behind every moment of your life to be anything except a willing puppet of the state, a personality-less cipher, or a spy.

The big question is whom are you a spy for?

It's in answering this question that this exhibition, despite its visually sophisticated, affectless quality, is so deep. Fiks has a genius for depth-charging ideas hiding beneath the surface, bringing them up, and tying them together. Whom are you spying for? The state, other queer men... or yourself?

There are no answers. The question is still riveting.

Fiks brings in, as a mute, dumb-waiter witness, the ghost of Guy Burgess, part of a holy coven of spies from the "right sort of people" in Cambridge, England, that included Donald Mcclean, Kim Philby, and Sir Anthony Blunt. Burgess and Blunt were both gay; Sir Anthony rose to the highest level of British society as the "Surveyer of the Queen's Pictures," that is the curator of the private royal collection, one of the greatest art collections in the world. He was also a foremost expert on the work of the 17th century classical French painter Nicolas Poussin, an enthusiasm I shared with him, being (as was Picasso) a great Poussin fan myself. Poussin, no big surprise, had a sizable queer underground following through the centuries after him; his stagy pictures have a frozen quality that still bleed recognizable feelings, often homoerotic, at the edges. In my gay science fiction novel Mirage, from 1991, I brought in Poussin's "The Baptism of Christ" at the National Gallery in Washington as a symbol for passions that are impossible to suppress.

This question -- how far can you go to suppress passion? -- is a constant in queer studies, so the element of hammer-and-sickle repressed homosexuality in Stalinist Russia is an excellent way to approach it. Stealthily.

In Fiks's "Lenin Museum," Guy Burgess is seen not so much through Burgess's narrow focus, but through the strange, enigmatic presence of one "Anatoly," a 27-year-old electrician and amateur accordion player who was known to be Burgess's Russian lover after Burgess defected to the Soviet Union in 1951. Fiks tries to reclaim Anatoly as a gay working class hero, that is, as a standard bearer for the queer working class that the Russian Revolution had promised to protect, as it would the entire working class, against capitalist oppression.

The inconvenient truth was that Russia's once important "queer colony," an underground gulag in its own terms, was steamrolled under a strictly puritanical Soviet regime. So much so that even though there are numerous books, films, and other accounts of the famous "Cambridge 5" (one of the spies' actual identity never came to light) and certainly of Burgess, no one knows Anatoly's last name, or what he actually looked like. As Fiks says, "So little is known about LGBT history [in the Soviet Union] that we have to create it ourselves."

Fiks sees Guy Burgess as an illuminating link to the plight of Soviet-era working class gays. He told me, "While the Soviets needed Guy Burgess, they allowed Anatoly to be 'free.' That is, he could freely associate with Burgess and could travel with him," while the rest of Soviet gay men were completely under the eyes and thumb of the KGB and Soviet repression, to a degree that is hard to imagine in the U.S., even back in the closely guarded 1950s. In the U.S., even through the Cold War, there were clandestine places where homosexuals could meet, drink, and spot each other. There were also hotels, guesthouses, bathhouses, and resorts that allowed genuine sub-rosa coupling, usually with the proviso that the cops were well paid off.

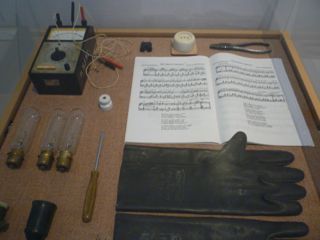

Anatoly, 2014, Electrician's tools shown with a subtitled film lasting 47 minutes on an attempt to envision "Anatoly."

In the USSR, this did not exist, because Stalin's eyes were everywhere.

On the other hand, the kind of casual, often fatal violence that stalked queer men in the US also did not exist in Russia -- simply because there were too many eyes watching out for that as well. So although gay men in the Soviet Union never felt free, they were not easily rolled and murdered in dark back alleys the way their counterparts in the US were. They were blackmailed, shamed, or internally exiled, but the too obvious permission to kill them that American macho culture afforded gay-bashers, did not happen. However, as in the US, in the USSR cops tried to get gays to inform on each other. This was especially true for those in the Russian "intelligentsia," who worked in universities or directly for the Party. Informing was offered as the only way out of a humiliation directly leading to suicide, so trust in any form was impossible.

This made it extremely difficult for Russian men to meet one another, and almost impossible for them to have any kind of extended relationships. Since Russian families often shared their apartments with other families, and having a private dwelling was unheard of unless you were exalted in the Communist pecking order, as a single or closeted Russian you had no place to bring anyone for an erotic encounter. So most were extremely fleeting.

The Russian queer-lingo for those places where quick meetings might take places was "pleshka," meaning literally a "bald spot," and one of the main attractions of "The Lenin Museum" is a 9-painting series called . . . what else? . . . "Pleshkas of the Revolution." The Russian Revolution was supposed to bring about universal liberation; it was a lie. In keeping with this feeling--the constant lie taken as the truth--Fiks's paintings are so droll, so bluntly banal, that they verge on humorous. They use a rolling, deadpan, Neo-Soviet Realism repressive style to signify what's going on outside of view, presenting a National Geographic survey of Mother Moscow, with a sly nudge to the ribs to let you know what you are looking at.

Sometimes it's a basement "loo" at the Polytechnical Museum where generations of queer men had Dollar-Menu-style quicky sex, knowing each other "biblically" down the stairs while avoiding each other assiduously on the street. Other times it's a train station, a school, or a famous park or garden whose leafy benches and bushes, scary and dangerous as they were, were the sole outlet for forbidden feelings and release.

One of my favorites shows the spire of Spasky Tower, below which is another pleshka known to generations of Russian gays as the "Toilet under the Stars," because the tower is topped with the single Red Star of the USSR. The Russian Red Star gives the place "legitimacy," something that this period was always big on, as both sides, Russian and American, resorted to every trick in the playbook to show how anti-queer they were. Nathan Leites, a University of Chicago "psycho-political analyst," in Psychoanalysis and the Social Sciences, tried to use Freudian analysis to prove that Lenin was a repressed homosexual, and that all of Russian Communism followed suite from this. Freudianism became a Cold War weapon on both sides, and the New York Psychoanalytic Society and Institute, the major training institute for generations of American headshrinkers, became a bastion of relentlessly heterosexual, pro-American orthodoxy.

This whole history of Russian, especially Stalinist homophobia is fascinating because it shines a flashlight on the rest of Russian history, as is true of any homophobia, American, British, German, or Middle Eastern for that matter. The question is always how useful are queers to the regime; and how much sexual policing will be necessary to keep the social order in order? As the original idealism of the Russian Revolution became flattened by the threat of German fascism, abortion became criminalized and the KGB became convinced that the Germans had sent a ring of homosexual spies to Russia who could easily spread their influence through queer networks.

In a way, this has become a universal fear and story: the secret transmission of information through homosexual encounters. I understood this completely in my youth as a teenager hitchhiking through America. I quickly understood the secret gazes, words, and ideas presented to me. Yevgeniy Fiks has beautifully brought this back to us from Stalinist Russia in "The Lenin Museum."

The James Gallery at the CUNY Graduate Center, 365 Fifth Avenue at 35th Street (in the old B. Altman building) is free and open to the public from Tuesday to Thurday, 12 - 7 PM, and on Fridays and Saturdays from 12 to 6 PM. The gallery will re-open on January 6 after CUNY's holiday break. The Lenin Museum will be there until January 17.

Perry Brass's latest book, The Manly Pursuit of Desire of Love will be published in June, 2015. He is the author of The Manly Art of Seduction, How to Survive Your Own Gay Life, and numerous novels and books of poetry. His latest novel is King of Angels, a gay, Southern-Jewish coming of age story set in Savannah, GA, in 1963, the year of J.F.K's murder.