First a little quiz:

A) What do Rock Hudson, Alfred Lunt, Lorenz Hart, Rudolph Nureyev, Dana Andrews, Montgomery Clift, Leonard Bernstein, Zachary Scott and Dan Dailey all have in common?

B) What do Maurice Chevalier, Gary Cooper, Leslie Howard, Fred MacMurray and Preston Sturges have in common?

C) What do Marion Davies, Mary Astor, Loretta Young, Lupe Velez, Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, George Cukor, William Haines, Rod LaRocque and Nina Gore Vidal Auchinclaus Olds have in common. (Hint: the last persona mentioned were all names of Gore Vidal's sexually rapacious mother, Nina).

D) What do Marlon Brando, Monty Clift and John F. Kennedy have in common?

(Answers at the end of this piece!)

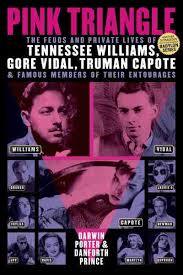

If you are completely stuck by this quiz -- and I hope to hell you are -- the only remedy is for you to run out this February, in time for Valentine's Day, and buy Pink Triangles, The Feuds and Private Lives of Tennessee Williams, Gore Vidal, Truman Capote, and Famous Members of Their Entourages, published by Blood Moon Productions. Blood Moon, in case you don't know, is what I call "the little press that could." It's a small publishing house on Staten Island that cranks out Hollywood gossip books, about two or three a year, usually of five-, six-, or 700-page length, chocked with stories and pictures about people who used to consume the imaginations of the American public, back when we actually had a public imagination. That is, when people were really interested in each other, rather than in Apple "devices."

In other words, we had vices then, not devices.

Blood Moon prides itself on mixing tabloid journalism, going to the source of gossip itself -- okay, hearsay, or the quickly deteriorating minds of aging witnesses -- with genuine moments of hard-work research (and there always is some of that in BM Productions books) to come up with their titles. The central author of most Blood Moon books is Darwin Porter, a long time veteran of what I used to call the "literary K-Y circuit"; here he is joined by Danforth Prince, a younger journalist and now Blood Moon executive.

Full disclosure: I have been a friend and follower of Blood Moon Productions tomes for years, and always marveled at the amount of information in their books -- it's staggering. The index alone to Pink Triangles runs to 21 pages -- and the scale of names in it runs like a Who's Who of American social, cultural and political life through much of the 20th century.

This in itself is the real story of Pink Triangles and why you might want to get the book. The three gay writers at the center of the book were not by any means at the center of American literary life during their period, which was basically from the end of World War II until the advent of Ronald Reagan, who basically brought on the cultural and economic idiocy we're living in, making the world safe for stupid people. But they were fixed posts around which a huge amount of our change in cultural, sexual and media information flowed. They were also very much a part of that era in which writers were still big media and cultural stars.

That is, high school kids could easily identify authors like Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Norman Mailer, Carson McCullers, the afore-mentioned queer trio, and maybe throw in Allen Ginsberg for good measure, by their photographs. This is something that does not happen anymore. Nowadays, no one knows what most authors look like. The written word is not dead. It just can't possibly compete with the effluvia of pop figures like Lady Gaga or Jay Z.

The period traveled by Pink Triangles also describes the last gasp of a white, often Anglo-Saxon-identified, Europe-centric public culture that ruled American social life and mores. It was also a time when people actually spoke in person to each other -- i.e., gossiped about film stars, and other public figures -- because there was so much that was being kept away from them by the mainstream media (although often pricked at, like a scabby wound, by the stealth drones at Confidential magazine). A lot of activities were, of course, regarded as strictly forbidden which meant that there was a vast below-sea-level iceberg of what we'd now call "down low" stuff happening. In other words, a great deal of "perverted sex" was going on, performed by all of the sexes. (I'm not sure if I can use the word "cocksucking" here, but you definitely can get my drift.)

Several things are fascinating about this trio of writers -- two of whom, Capote and Williams were definitely gifted; the third, Vidal, was a star witness and political canary-in-the-coal-mine of his time -- he was already writing about the Corporate state forty years ago. Item one is that they totally believed in the necessity and august role of great writing. It was something you plunged your entire being into, and it was very much a blood sport. The level of competition was intense and unforgiving. Item two: You didn't need an MFA to do it. In fact, the whole idea of today's university "creative writing industry" either infuriated or befuddled them. Two of them never went to college; Capote and Vidal started writing professionally right after prep school. Williams had only a sketchy bachelor of arts in English from the University of Iowa, meaning that today he'd have a difficult game getting into academia.

Vidal was famous for loathing academics, who he felt kept him out of the "lit'rary" canon, especially since most were closet queens anyway; Vidal made his great splash and success d' scandal with The City and Pillar, an amazing coming out book from 1948, which sold 2 million copies and ended up blacklisting him from big-ticket New York publishing for a decade.

Still, the three thrived in a very elitist Ivy League-ish environment -- and their circles swirl and lap around the Hyannisport-Palm Beach Kennedys, the Merrills (as in James Merrill, poet-heir to the Merrill-Lynch fortune), Diana Vreeland's nosebleed high style, Hugh Auchincloss's fox-hunting crowd (Auchincloss, Vidal's once stepfather, who divorced Nina in order to marry Janet Bouvier, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis's mother), to name only a few. These guys understood that to stay alive, you had to be where the money and power lived, and there weren't a lot of alternatives to that.

Vidal ended up leaving his entire, fairly considerable fortune to Harvard, even though he never went there and often bad-mouthed the place. But there was something about the cachet of big-money, big-power Harvard he could not shake off.

The third fascinating thing is how wonderfully human they were -- bitchy, scalding as they could be; still very fragile. They all had terrible drinking and drug problems, the result I'm sure from the constant personal affronts thrown at them. Tennessee Williams was frequently attacked by critics like the New York Times's Howard Taubman, as one of the "sick elements" in American theatre; Capote's agent, the revolting Swifty Lazar, openly referred to him as a "fruit"; Vidal who had politics in his blood through his famous senator-from-Tennessee grandfather, tried to play with the big boys in a high profile election for Congress, and was pilloried for it.

This brings me to one of my most favorite Williams anecdotes which unfortunately is not in Pink Triangles: his awful snub from poet W. H. Auden. Auden was about a decade older than Williams, and already a world famous poet when Williams finally made his great success with The Glass Menagerie. He wanted to meet the poet so much, and so had a friend of his who knew Auden bring him over to Auden's apartment on St. Mark's Place in the East Village. Auden had already made up his mind that Williams was just a bit too "minty" for him; that is, he was too flagrantly queer, and his work was too questionable. Auden was a High Church Episcopalian who believed that queerness was not altogether unnormal, but was definitely "wicked." He had been tipped off by this mutual friend that Williams was coming, and when the doorbell rang, he pretended not to hear it. Then he made sure that no one else in his household, like his partner Chester Kallman, did.

Williams decided to try again on another day. He sent out "feelers" through the queer grapevine that he very much wanted to meet the great poet and held him in the highest regard. Auden was unmoved. He would have nothing to do with Tennessee Williams. The anecdote about W. H. Auden's snubbing of Williams is included in Auden in Love, The Intimate Story of a Life Long Lover Affair (Simon and Schuster, 1984), by Dorothy Farnan, an Erasmus Hall High School English teacher who married Chester Kallman's father, Edward, after originally falling for Chester.

Auden's snubbing of Williams reminds me in some ways of the critical reaction to Blood Moon's books. They can be salacious, but they're never stupid, and the amount of real information in them is impressive. But, like Rodney Dangerfield, they still get no respect. A perfect examples of this came when BM published, in 2004, Katherine the Great: Secrets of a Lifetime Revealed, about the very private life of Katherine Hepburn. Talk about being pilloried! The book was damned from one shore to the next, because it came out, finally, with the news that Hepburn's most intense, satisfying relationships were with other women, and that her relationship with Spencer Tracy, considered one of the great romantic trysts of the twentieth century, was basically platonic: Tracy was also a secret bisexual. Therefore the reason why the two never married was not because Tracy was Catholic and didn't want to divorce his wife; it was that neither Hepburn nor Tracy ever intended to marry one another.

This information was held as totally spurious gossip, until, in 2007, William J. Mann published, through Macmillan in New York, a full length bio of Hepburn, Kate, revealing exactly the same thing. Mann's book was reviewed nicely in the New York Times, and he and the book were promoted to all get-up nationally. No one blinked hard at it.

Another example was in 2012, when Scotty Bowers's tell-all book from Grove Press Full Service: My Adventures in Hollywood and the Secret Sex Lives of the Stars was released. Bowers, 88 at the time, and a once-flourishing call boy and procurer, told many of the same stories Darwin Porter has been telling all along. Bowers's book got a full page write up in the Times, and review in the Times Sunday book section. Life I realize is not fair, but it's time for Blood Moon Productions to get the respect they fully deserve. These books answer a simple but sometimes slippery question: when does "dirt" stop being "filth," and become simply something that people who care have a right to know?

Answers to quiz questions:

A) All of these men frequented the Everard Baths, in Manhattan, a once notorious bathhouse famous for its gay cavorting.

B) All of these men succumbed to the charms of Gore Vidal, or at least he reported so.

C) All of these people were sexually gratified by "Rhett Butler" -- oh, sorry, Clark Gable.

D) All sexually pleasured by Tennessee Williams (according to Williams!).

--

Perry Brass is the author of 16 books. His latest is 'King of Angels, A Novel About the Genesis of Identity and Belief', a finalist for a Ferro-Grumley Award for Gay and Lesbian Fiction, awarded a Bronze Ippy for Best Young Adult Novel, 2012. His previous book was 'The Manly Art of Seduction'; both books are available as Ebooks and in print. He is currently working on a book about the power of desire, and can be reached through his website.