UCLA made a big mistake returning $425,000 donated by Donald Sterling for kidney research and canceling an agreement that would have brought Sterling's gift to $3 million over seven years.

UCLA's action on Tuesday came soon after the NBA announced that it had banned Sterling from owning an NBA team or associating with the NBA for the rest of his life after the Clippers' owners' racist rants were leaked (apparently by his mistress) to the media.

The Los Angeles Times quoted a UCLA spokewoman, who explained: "Mr. Sterling's divisive and hurtful comments demonstrate that he does not share UCLA's core values as a public university that fosters diversity, inclusion and respect. For those reasons, UCLA has decided to return Mr. Sterling's initial payment of $425,000 and reject the remainder of a $3-million pledge he recently made to support basic kidney research by the UCLA Division of Nephrology."

UCLA should have been more strategic. It should have taken the money, but stipulated that it would not name a building, research center, or anything else after Sterling, nor give him an honorary degree or any other award.

By doing so, UCLA would have put the ball in the Clippers owner's court. If Sterling accepted those terms, his money might contribute to research that could save lives. But if he rejected those terms, it would expose the kind of phony philanthropist he really is -- donating the money only to wash his dirty reputation and burnish his ego.

The great Jewish thinker Maimonides observed that an anonymous gift is "a commandment fulfilled for its own sake," rather than done in order to obtain honor.

If Sterling was familiar with Maimonides' words, he didn't take them to heart.

Sterling is well known in Los Angeles for placing expensive full-page and half-page self-congratulatory ads in the Los Angeles Times extolling his own generosity. A photo of Sterling inevitably adorns these ads, along with photos of the heads of dozens of nonprofit groups in the Los Angeles area who receive Sterling's largesse. Many of these organizations, in turn, bestow awards on Sterling for his allegedly humanitarian gestures, which Sterling promotes in these ads. The ads are always in the same format and have an amateurish quality that have led many Times readers to wonder why someone as wealthy as Sterling (his estimated worth is $1.9 billion) can't hire a better PR flak to design more attractive ads.

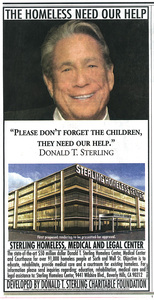

In 2006, Sterling paid for a newspaper ad announcing that the Donald T. Sterling Charitable Foundation would develop a "state-of-the-art $50 million dollar" project for "over 91,000 homeless people" in LA's Skid Row neighborhood. The ad included a photo of a smiling Sterling above the quote: "Please don't forget the children. They need our help." At the time, many homeless advocates criticized the plan for being more like a mega-warehouse than a social service agency. But they need not have worried. Although Sterling spent millions of dollars to buy properties in the area, he never carried through on the homeless project. And now that the Skid Row neighborhood has gentrified -- pushing many low-income people out of the area -- Sterling is sitting on valuable property.

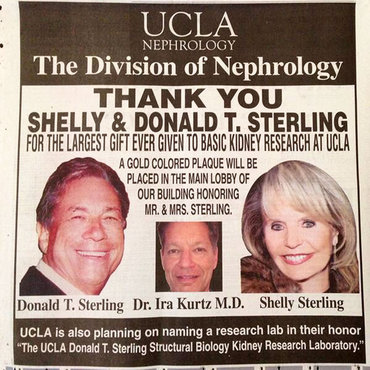

Sterling made sure that the world knew about his gift to UCLA, even before the university had announced it. In March, Sterling took out an ad in the Los Angeles Times to boast about his good deed. The ad, which was made to look like it was put there by UCLA, said that the university planned to name a kidney lab after Sterling and his wife and that a "gold-colored plaque" honoring them would be placed in the lobby of a campus building.

On Tuesday, UCLA denied that it was going to name a lab after Sterling and his wife or even to install the plaque that Sterling's ad boasted about.

So if there were really no strings attached to Sterling's gift to UCLA -- no Sterling lab, no Sterling building, no Sterling "man of the year" award, not even a Sterling plaque -- it makes no sense for the university to return the money.

Yes, Sterling has a repugnant history of racism, as I noted in my article on Sunday about his long track record of blatant discrimination against Blacks and Latinos in his rental properties. But UCLA, and almost every other university and college, hospital, museum, and other nonprofit organization in Los Angeles and the around the country, has taken lots of money from disreputable people and corporations who hope that acts of charity will cleanse their reputations or perhaps smooth their path to heaven when its time for their children to examine the will.

In the early 1900s, Robber Barons created philanthropic foundations to help them wash their dirty reputations with charity. John D. Rockefeller began his philanthropic foundation to try to divert public attention from his reputation as a vicious robber baron, particularly after his private army killed striking workers, women and children at the Ludlow Massacre in Colorado. Rockefeller endowed the University of Chicago (my alma mater) which went on to become a great institution, but fortunately isn't named after his initial benefactor. (Rockefeller University in New York has that dubious distinction). Not many people know that Leland Stanford was a notorious railroad tycoon, but everyone's heard of Stanford University.

When I taught at Tufts in the 1970s, the university bestowed an honorary degree on Philippines First Lady Imelda Marcos -- for "humanitarianism" no less! -- in exchange for a multi-million grant from the Marcos Foundation to create a Marcos Chair at the university's Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, at a time when her husband, president Ferdinand Marcos, was being criticized by human rights groups. The obvious goal of Marcos' philanthropy was to cleanse his reputation as a brutal dictator. When Imelda visited the Tufts campus in 1977, over 1,000 protesters disrupted her visit. Newspapers were filled with articles about the protests, which only heightened public awareness of the dictatorship's brutal regime. Having failed to gain the positive publicity he was hoping for, Marcos eventually withdrew the gift to Tufts. As a result, the university got stuck with a double-whammy -- it sold its soul to a dictator and, in the end, didn't get his money!

In the past decade, the wealth of the upper tier of the 1 percent has grown dramatically while living standards of 90% of the American people have stagnated or declined. Public opinion polls show that Americans are increasing angered by this concentration of wealth and the resulting concentration of political power. In response, many big corporations, Wall Street banks, and billionaire businesspeople have expanded their charitable giving to help divert attention away from their rapacious business practices. Walmart and the Walton family, the Koch brothers, the tobacco companies, and many others would prefer to be known as "philanthropists" rather than modern-day Robber Barons.

Not all philanthropy is self-serving and ego-centered. There are many people who make anonymous donations to worthy causes for the best of altruistic and humane reasons. There are organizations like the Liberty Hill Foundation in Los Angeles and its counterparts in other cities that take donations from wealthy individuals and direct the money to grassroots organizations that mobilize people to change the very system of privilege and power that helped the donors amass their fortunes. They are following Martin Luther King's adage: "Philanthropy is commendable, but it must not cause the philanthropist to overlook the circumstances of economic injustice which make philanthropy necessary."

So the question for non-profit organizations -- a university, a hospital, a homeless shelter, an environmental organization, or a civil rights group (like the NAACP, which honored Sterling with a Lifetime Achievement Award five years ago and was about to do it again in two weeks before the current controversy forced it to withdraw the honor) -- is what standards should they have for bestowing honors on their donors. When is a donor such a disreputable person (or corporation) that its donation -- and the strings attached to it -- soils the reputation and moral standing of the nonprofit group, despite its many good deeds?

So if UCLA could have persuaded Donald Sterling to donate to its kidney research program without any strings attached -- perhaps even insisting that he not promote his philanthropy in newspaper ads or billboards -- I see no harm in the university taking his money and using it to pay for much-needed medical research. I doubt Sterling would have accepted those terms, but it would have been interesting to find out. But by canceling its agreement with Sterling, UCLA pre-empted the slim possibility that Sterling would take Maimonides' advice.

Peter Dreier teaches Politics and chairs the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. His latest book is The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame (Nation Books, 2012).