Should this blog provide consumers guidance or post-facto commentary? I'd like to think it could do both, but timelines and deadlines and laugh lines and Nazca lines and whatever lines I can hand you have a way of diverging, leaving me enthusing or fuming over an all-too-precipitously expired show or event. The Los Angeles County Museum's two major spring exhibits, for instance, have just faded from the radar, and although they are traveling shows, they seem to have finished their tours by the banks of the Pacific (although no such banks sponsored either show). Should I then simply shrug them off? I saw 'em, you missed 'em, end of story? No, seeable or post-seeable, both shows are worthy of contemplation, bringing up issues larger than themselves - as it seems they were designed to do.

"American Stories: Paintings of Everyday Life, 1765-1915" expanded on our country's social history through pictures, while expanding equally on the nature - the manner(s), the style(s) - of that picture-making. In other words, it is about visual culture and art. Organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "American Stories" looked at American Life as American Life emerged. "American Stories" compiled many of our masterpieces - our singular images, the pictures that popped up in our social studies books and/or that stopped us in our tracks when we meandered through the Met or Art Institute of Chicago or even LACMA - into an overarching narrative, a look at us looking at us. We're supposed to mistrust such "master" narratives, but this one played its hand so transparently that it made us delightedly complicit in its presumptions. And it was hard to argue with its premises, or to reject its informative and clearly written wall labels, labels that exposed the iconography of just about every picture on the wall. This is what happens when art historians take visual culture seriously - and visual-culture historians take art seriously.

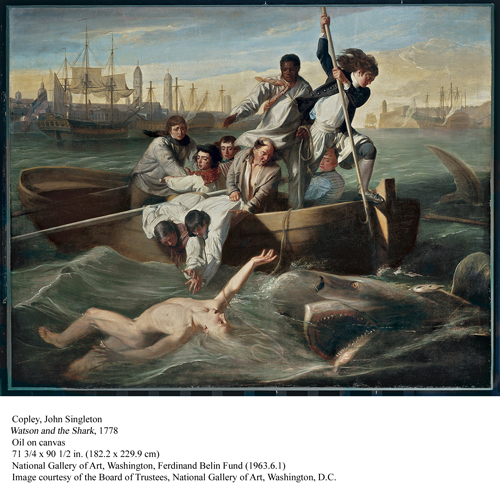

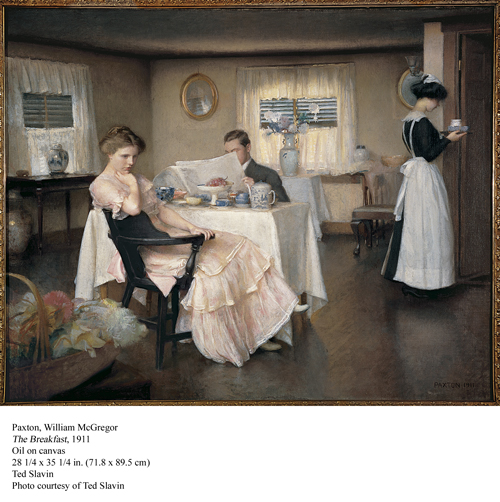

"American Stories" divided its century and a half into five thirty-year groups, exposing the shared purposes, and the shared and diverging methods, of the artists in each period. The rural focus and moralizing emphasis of painters before the Civil War, for instance, contrasted markedly with the more urban and more directly reportorial viewpoint of "gilded age" painters - whose adoption of impressionist techniques also differed from the almost self-effacing naturalism of their forebears. Certain artists such as Winslow Homer transcended these differences, but the show was able to place even Homer's expansive contribution in context - that is, in several contexts. Beautifully but not obtrusively installed at LACMA, "American Stories" was gratifyingly full of paintings you wanted to look at as paintings; but it made it not only okay, but necessary, to look at them as illustrations, propositions, ideas, moments of theater. Whether it's an image of a man saved from a shark or of a husband and wife sharing a meal, these painters put you in the picture. And the light! The detail! Light is one thing painters as diverse as John Singleton Copley, Thomas Eakins, and Mary Cassatt knew how to shape and focus; detail, whether handled by George Caleb Bingham, John Singer Sargent, or William Glackens, is also directed toward the projection of a vivid narrative experience. You get the feeling that "American Stories" ends in 1915 chiefly because that's when painting was relieved of its job of storytelling - that most American of impulses - by motion pictures.

The first room of "American Stories" was the single one not organized chronologically. Instead, it arrayed two groups of paintings opposite one another. One group's three paintings (including John Singleton Copley's Watson and the Shark and Homer's The Gulf Stream) shared a common sub-theme, the presence of African Americans. The other group's four paintings (including Copley's portrait of Paul Revere and John Sloan's Chinese Restaurant) shared a very different thread: the presence of tea. I suspect the curators were finding premonitions an early 21st century narrative in our artistic history, positing our first African American leadership against a Tea Party - and acknowledging that both phenomena are as American as, well, apple pie, rebellion, racism, and liberty.

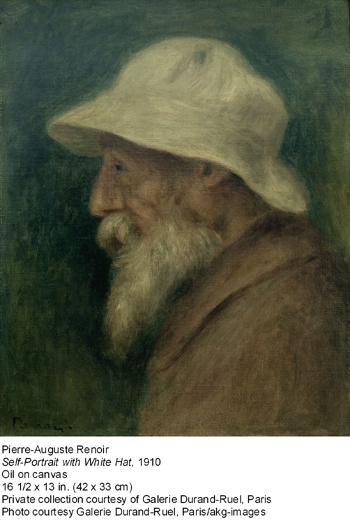

If I regret selling too late an endlessly informative, engrossing show like "American Stories," I'm just as happy discussing "Renoir in the 20th Century" (organized by LACMA and the Musée d'Orsay in collaboration with the Philadelphia Museum of Art ) in hindsight. If Pierre-Auguste Renoir may be your favorite impressionist, the works he painted in the latter part of his career are very likely deal-breakers for you. His rich, glowing palette has for the most part been reduced to wispy tonalities; his complex compositions and his embrace of everyday life have dissolved. Instead, the work Renoir did after breaking with impressionism and turning toward a more classicized view of the world is filled with oranges and light browns, still lifes and solitary figures, and a self-consciousness about Art and Picture-making that nagged at you from room to room. The only thing left from the Renoir of downstairs-bathroom posters is the light, nervous brushstroke, more feathery than ever. A few small landscapes break out some of the rich color and bravado brushstroke of old, and, by contrast, the several self portraits look mournfully but pitilessly at the geezer Renoir had become; these were, however, the only gripping pictures in "Renoir in the 20th Century."

Still and all, the exhibition made a decent argument for taking the old guy seriously. Although only his paintings of men treat them like humans - his renditions of women and children, even his own kids, all have the same puffy, simpering non-face - you got a sense of Renoir looking for something in the human condition; the figures may be pleasant, but they are not drab. In particular, his portrayals - including in bronze - of several female models glow with a gentle erotic charm (which in our neo-prudish era, of course, freights them with a dirty-old-man subtext). What finally made the argument for the late Renoir, though, was the inclusion of works by Bonnard, Matisse, Maillol, and even Picasso that clearly evince the influence he had over these later modernists even - especially - in his dotage. Renoir's harlequins and huntsmen and harem girls may have been tired motifs even when he painted them a hundred years ago, but they signaled a renewed appreciation of traditional themes which the younger artists turned into a rallying cry. Who knew that the neo-classicism of the jazz age began in the luxe, calme et volupté of an arthritic ex-impressionist's retirement plan?