Brion Gysin did indeed let the mice in (as one of his books proclaims in its title). Known now mostly as cohort to William S. Burroughs, Gysin was the one who introduced Burroughs to the cut-up method. He was also a writer, a painter, a poet, a "sound poet," a musician, an electronic artist practically avant la lettre, and an inspiration not only for Burroughs, but for legions of younger artists working in all disciplines, from Patti Smith to Keith Haring. Gysin's reputation as a postwar decadent precedes him (he was a restaurateur in Tangier and a Beat Hotel denizen in Paris, and contributed to Alice B. Toklas' much-touted cookbook), but his oeuvre, in its many forms, has been all too little appraised, much less appreciated, as art. The retrospective at New York's New Museum, ending Sunday (Oct. 3, but going on to Paris), takes care of that omission once and for all. It exposes Gysin as a restless experimenter with a consistent vision, an inconsistent style, and an enduring commitment to several art forms, not least hybrid, intermedial practices such as visual poetry and performance art.

BRION GYSIN, Multi-screen projection of scratched 35-mm slides, 1961/1978-81, Photograph: NKubota

The inconsistencies in Gysin's style, in fact, allowed him to swing among, and fuse, various media even as he swung between calligraphic gesture and the rigors of typography, detailed drawing and expansive experiment with light, sound, film and video. Gysin's jack-of-all-tradesmanship bothered those in his day who would publish him, exhibit him, or sponsor him; but, as this retrospective emphasizes, he was relatively adept at everything he did -- and, more important, restless not only in his means but in his goals, to the point of almost continuous innovation.

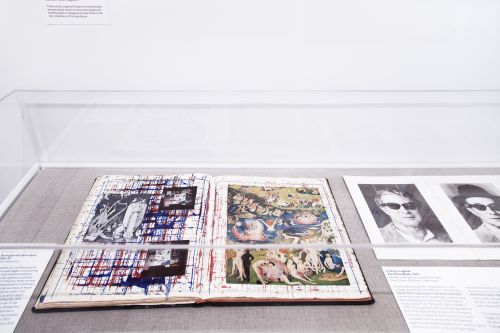

BRION GYSIN and WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS, pages from The Third Mind, 1965, ink and type on paper, 12 x 9 inches, and FRANCOIS LAGARDE, The Three Minds, 1978, Gelatin-silver prints mounted on card, 9 1/2 x 21 3/4 inches overall, courtesy William S. Burroughs Trust, Lawrence, Kansas, Photograph: NKubota

Besides his introduction of Cut-up composition (in fact a renewal of the Dada method), Gysin's prime contributions to the Beat discourse were his abstract calligraphic writings -- spontaneously generated illegible texts that resulted from his early association with surrealism and his mastery of both Japanese and Arabic -- and his supposedly mind-bending Dreamachine. That device gives the survey its subtitle, but as a centerpiece it proves rather anticlimactic. Peculiar and apparently very effective in its day, the whirling light show in a darkened room seems now as dated as -- well, as a whirling light show in a darkened room. The Dreamachine comes to us as an historic artifact; everything else around it, from the myriad pages Gysin pasted up with and without Burroughs (among other collaborators) to the ritualistic sound-gesture performances captured on film, proves far more fascinating and far more aesthetically durable. There is almost a funhouse feel to the show as you move from vitrine to headphones to wall-length painting to projected image, and you get a contact high without even diving into the dark.

BRION GYSIN, Dreamachine, 1961, Perforated metal, electronic motor, lamp, 46 1/2 x 11 3/4 inches (height x diameter), Musee de l'Art Moderne de la ville de Paris, Photograph: NKubota

BRION GYSIN, Calligraffiti of Fire, 1985, Oil on canvas, 51 1/8 x 645 5/8 inches, Collection Academy of Everything is Possible, Courtesy October Gallery, London, Photograph: NKubota

In the book accompanying the exhibition, curator Laura Hoptman calls Gysin a "psychonaut," emphasizing not just his practical reliance on psychoactive drugs, but his artistic ideology of "derangement," his belief that "by erasing the artificial distinctions between words and images, and disentangling the two from their determined meanings, new meanings -- those that had been hidden or suppressed -- would arise, opening the way to new psychic vistas, even a new consciousness." In this, Gysin was a bridge -- a crucial one, as the show demonstrates -- between the perceptual revolution of surrealism and the revolution in consciousness that permeated the 1960s.

BRION GYSIN: DREAM MACHINE, exhibition view, Photograph: NKubota

The book, published jointly by the New Museum and the very hip art press Merrell, is no simple accompaniment-cum-souvenir to the exhibition. Even more than most exhibition catalogues these days (and there have been some very good ones produced of late, to the point where I'm thinking it's a "silver age" of museum publications), Brion Gysin: Dream Machine is a must-have for scholars and fans, literati and arterati, the converted and the curious alike. Its several eminently readable essays treat Gysin neither as saint nor madman, and certainly not as the mere itinerant so many of his contemporaries considered him, but as a modernist thinker and seeker, at once hungry and doubtful, spiritual and profane, a soul unmoored from physical address and perceptual fixity but tethered passionately to images and objects, words and sounds. The book adds to a growing bibliography on Gysin, but it is the first in English to treat him first and foremost as a visual artist, considering his writing, soundmaking, performing, and interstitial spelunking as entirely of a piece. Here, Brion Gysin the intermedialist finally emerges, not simply sporting several hats at once, but wearing a whole polyvalent outfit of his own design -- a king, genial and quirky but masterful nonetheless, of many interfacing trades.