Yesterday's hot items are today's history, obviously enough, but today's history is also today's hot item. I marvel continually at the rediscovery of painters who made a splash three to four decades ago and then eased their way to the margins to allow younger folk the limelight. Sure, there is a wholesale revival of "mid-century modern" going on at the moment, giving new currency to hard-edge painting, pop art, and even abstract expressionism; but even those who had nothing to do with those movements, or whose success came in succession, are getting a new day in court. Not everything old looks new again, but if it's the right age, we can give it a second wind.

The artists being brought back out of the shadows have by and large not stopped working for a second; their new work's out-of-left-fieldness can be refreshing, and their old work looks startlingly hot, at once familiar and unanticipated. There's a certain market strategy in all this, of course, allowing the piled-up inventories of galleries, studios, and estates finally to move the stuff -- and the reputations -- that didn't move the first time; but the work hasn't been overexposed, at least not for decades, and its durability and continued freshness dispels cynicism. Ars longa, indeed.

One thing you notice about this work from back when and/or by artists from back then: it's honest. It may evince formal and intellectual calculation, but what drives it is the need to exist, the need to embody the artist's process of exploration, the need to communicate a struggle with concepts. This is art, not product. Sure, there's plenty of such noble art being produced, and shown, nowadays as well. But is it still the norm? A third of a century ago, it's what we expected to see when we walked into a gallery; now, it's a treat to see it.

It was a treat to see the recent work of two veteran New York painters in Los Angeles recently, buffered by a microspective of a third, very different, much older and deader painter. Even back in her day the latter artist was knocking us on our butts with the rawness of her manner and her approach; but it has been hardly less exhilarating to see her junior seniors keep on keeping on, refining the methods and mindsets that had gained them attention and respect as young turks.

ALICE NEEL, Linus and Helen Ava Pauling, 1969, Oil on canvas, 48 x 42 inches

Photo: Malcolm Varon, Copyright the Estate of Alice Neel, Courtesy L.A. Louver

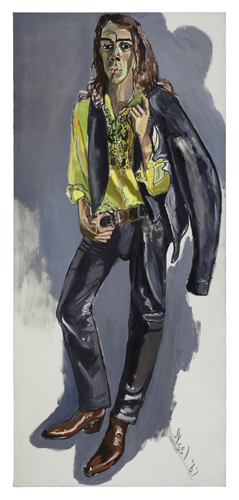

Alice Neel's retrospective is making its way around Europe (having just left Houston, its only American venue) and not coming to Los Angeles, so we made do with a clutch of representative paintings at Venice's LA Louver Gallery, all portraits (as was Neel's wont) dating from the 1940s through '70s. The selection was hardly comprehensive, but it was typical: the sitters all seemed as if they were well known to the painter, and she treated them at once as intimates, as vital human beings, and as great subjects -- things as much as personas -- to paint. To "capture" her subjects Neel employed a virtuosic blend of bravado and niggling detail whose lines never stop moving and whose colors (even early on, when she employed a palette of mostly earthy, almost edible browns) glow with mid-wattage electricity. This is the happiest expressionism you'll ever see; you always feel as if Neel was in a better mood than her sitters, and what changes from picture to picture is whether they wind up infected by her sunny demeanor or hold on to their dyspepsia like good New Yorkers. Finally, though, Neel wanted them to be themselves, and even if she got them smiling she dug into their personalities, sometimes embellishing their images with background clues, but more often opening them up to us by finding and exaggerating their body language and even the subtlest facial contortions. Also, Neel saw them all - all, irrespective of age ¬- as sexual beings, potentially desirable and clearly desiring, "hankering, gross, mystical, nude," as Walt Whitman put it. You can imagine why, when Alice asked me to sit for her, I balked even as I thrilled to the idea; by time I got up the gumption to say yes, she was on to other things - er, people.

ALICE NEEL, Joey Scaggs, 1967, Oil on canvas, 80 1/8 x 35 7/8 inches Photo: Malcolm Varon, Copyright the Estate of Alice Neel, Courtesy L.A. Louver

ALICE NEEL, Abe's Grandchildren, 1964, Oil on canvas, 40 1/8 x 30 inches Photo: Malcolm Varon, Copyright the Estate of Alice Neel, Courtesy L.A. Louver

Alice and her paintings were fixtures on the New York scene in the halcyon days, even when painting fell out of fashion. Or did it? The 1970s -- when Neel truly began to emerge from her "painter's painter" confine -- also saw an explosion in painterly experiment. Perhaps it came about because, after hard-edge, pop, and color-field, painting was eclipsed by minimalist sculpture, earthworks, conceptual art, performance, video, and all sorts of "new media." This allowed painters the freedom to wail away in their studios and at one another's ideas. This was the heady, homey mix in and among which John Seery and Robert Rahway Zakanitch (then spelled "Zakanych") emerged and rose to prominence. Seery's elusively but luminously colored, eccentrically composed canvases and Zakanitch's florid but rhythmic painted patterns were among the most celebrated of their ilk. But when Lyrical Abstraction waned and Pattern Painting petered out, Seery and Zakanitch continued to explore the manners and motifs that had initially motivated them, only released from the expectations of the art world (most especially, and perhaps dauntingly, their peers).

JOHN SEERY, Amazonia, 2009, Oil on canvas, 111 x 80 inches

Fine, but what have they done for us recently? Zakanitch has continued to exhibit with some regularity, while Seery has been more reticent (although more active in Europe than here). But neither has let his meat loaf, certainly not to judge by the recent works each showed. At the Garboushian Gallery in Beverly Hills Seery showed several large new canvases (that seemed larger due to the gallery's own compressed size) in which recur the saturated color, numinous composition, and graceful but urgent gesturality that drove his earlier work. This time, though, Seery's paintings admit more brushstrokes amid the blots and flows, and the color has taken on a translucency that proposes a remarkable visual depth. The canvases glow like stained glass windows,, or at least can when approached from the right angles. Seery no longer allows himself any painting for effect - not that he ever emphasized that, but it used to be an arrow in his quiver, and now, instead, he paints for energy.

JOHN SEERY, Untitled #5, 2008, Oil on canvas, 88 x 75 inches

This is expressive painting, not least in its total lack of self-consciousness. It may be full of thinking, but it is free of cleverness, and its coarse painterly tumult is designed to cohere slowly, to appear offhand and ruminative at first and then to pull together into a clearly un-accidental force field.

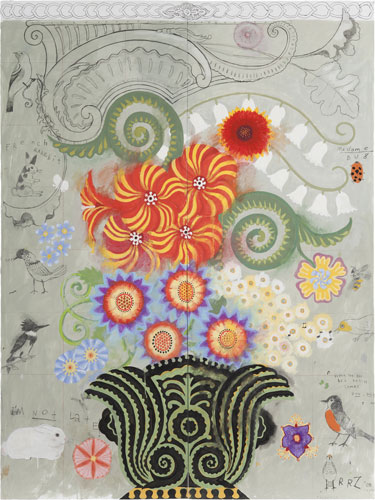

ROBERT RAHWAY ZAKANITCH, Rococo Revisited, 2008, Gouache on paper, 96 x 72 inches Photo: Eric Vigil

This guileless conception and deftly laborious execution marks Zakanitch's latest paintings and works on paper (shown at the Samuel Freeman Galley in Santa Monica's Bergamot Station) no less, especially given the humor and exuberance they radiate. Whether in the acrylic flower forms he has burgeoning off small panels or the vast, almost drapery-like gouaches on paper he has bedecked with yet more stylized floral, and animal, forms, Zakanitch celebrates nature - plants, birds, other wild beings - in a way that determines a fine line between the naïve and the elegant, the dopey and the exquisitely limned, the hermetic and the expository. Written legends festoon the drawings, seeming to embody the critters' thoughts but also driving home the quality, even identity, of these large, crowded artworks as narratives, anthropomorphic stories - or at least stories that attribute human reasoning to "lower" species - set in edenic gardens. Still stressing decorous elaboration, Zakanitch wants to draw our attention first and foremost to what's natural, not what's artistic. But In his hands art doesn't so much imitate life as adopt and contemplate its shapes and habits. This isn't mere pattern painting, it's pattern recognition painting, and the pattern being recognized is life itself.

ROBERT RAHWAY ZAKANITCH, June Burst, 2009-10, Acrylic on panel, 14 x 14 x 3 inches

Photo: Eric Vigil