ALFRED SISLEY, The Barge During the Flood, Port-Marly, 1876, Oil on canvas, 19 7/8 x 24 inches

Impressionism is art's easiest sell, at least nowadays. What once was taken as an affront to propriety is now regarded as the most natural and pleasing of artistic practices, a way of painting that reassures the middle class of its grasp on reality and reassures would-be painters that the act of painting is not that exacting a process. "Birth of Impressionism: Masterpieces from the Musée d'Orsay," recently closed at San Francisco's De Young Museum, seemed to be pitched to that comfortable view. It was a blockbuster show - right down to the dread term "Masterpieces" in its subtitle - one whose attendance records are doubtless being trumpeted even as I write this.

CLAUDE MONET, The Tuileries, 1875, Oil on panel, 19 5/8 x 29 5/8 inches

But "Birth of Impressionism" turned out to be a more subversive undertaking than it let on. Its organizers clearly love and respect the artists and their works even more than the rest of us do, because they strove mightily to put them in context, both with their times and with one another. Sure, there was plenty of what could be dismissed as eye candy on hand; but even the most reproduced or most (apparently) saccharine objects fell, finally, into place, the intents of their makers now as clear as their skills.

FREDERIC BAZILLE, Bazille's Studio, 1870, Oil on canvas, 38 5/8 x 50 5/8 inches

In fact, the show emphasized "Birth" over "Impressionism" or even "Masterpieces." The works were selected not (at least primarily) to seduce the eye once more, but to alert the brain to a dynamic and elaborate artistic development and to the social and political conditions that brought it about. Between the selection of objects and the wealth of extremely informative wall texts, "Birth of Impressionism" illumined a moment - well, string of moments - in French, and European, history whose implications we still feel. Nationalism, imperialism, relations between state and polity, the emergence of workers' movements, the recovery of a city and a nation from catastrophe, all these dramas of modern western civilization played themselves out on the streets of Paris and impacted the thinking of the men (and occasional women) who would similarly impact where art went.

EDOUARD MANET, Stephane Mallarme, 1876, Oil on canvas, 10 7/8 x 14 1/8 inches

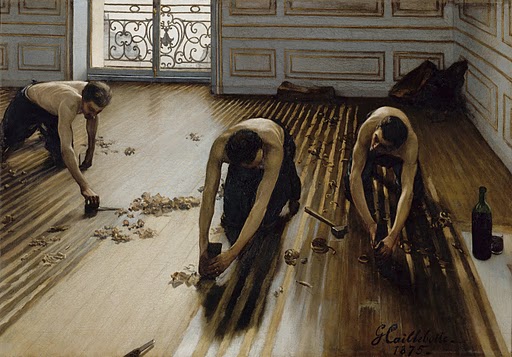

GUSTAVE CAILLEBOTTE, The Floor Scrapers, 1875, Oil on canvas, 40 1/8 x 57 5/8 inches

Impressionism, as constructed by this survey, evolved out of realism, the first direct challenge to the stylistic and subjective dictates of the Académie. Interestingly, the French government looked more favorably on at least some of these realists more than did the Academicians themselves, setting up a public dynamic that allowed "outsiders" such as Courbet and, especially, Manet to be received with at least some official approval. All bets were off the table, however, with the upheaval of the 1870 war between France and Germany, a conflict that led to the fall of Louis Napoleon's empire and the pitched class conflict in the streets of a ruined Paris. In the wake of this devastation - which the show documented with artworks in various styles, from academic heroics to the symbolist fabulations of Moreau and Puvis de Chavannes - Impressionism emerged as an art of the quotidian, a painting that did not reassert eternal verities but documented the changes and variations that comprise ordinary life.

PIERRE PUVIS DE CHAVANNES, Young Girls at the Seashore, ca. 1879, Oil on canvas, 24 x 18 1/2 inches

Whether painting snow in a backyard or spring light in a field, a family gathering in the suburbs or an artists' gathering in a café, the steam and bustle of a train station or the choreographies of people in the street, artists such as Degas and Caillebotte, Bazille and Fantin-Latour, Pissarro and Sisley, Renoir and Monet devoted themselves to the actual moment, not the artificially momentous. No wonder that their first exhibition was held in the studio of the photographer Nadar; their pictorial ideals were shaped by the still-new medium of photography.

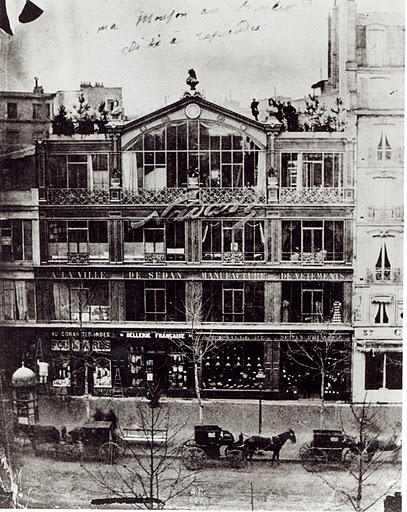

NADAR'S STUDIO

HENRI DE TOULOUSE-LAUTREC, The Photographer Sescau, 1896, Color lithograph poster with brush, crayon, and spatter, 24 x 31 1/2 inches, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts

Photography dominates the exhibition, still on view (through September 26), that the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco mounted to accompany "Birth of Impressionism." If anything, "Impressionist Paris: City of Light" is an even more fascinating, and hardly less visually rewarding, show than "Birth" was. Devoid of broadly popular artworks (beyond a few choice Toulouse-Lautrec posters), "Paris" documents the physical, visual, and social milieu in which Impressionism emerged. Featuring everything from photographs to posters to illustrated newspapers to lithographs to broadsides and even a few paintings - and labeled with wall texts even more informative than those in "Birth" - the show describes the vitality of a city in transition, a city we think of as the cultural capital of the 19th century but which is here revealed, through its art and its intellectual life, as a center that nearly died in order to be renewed.

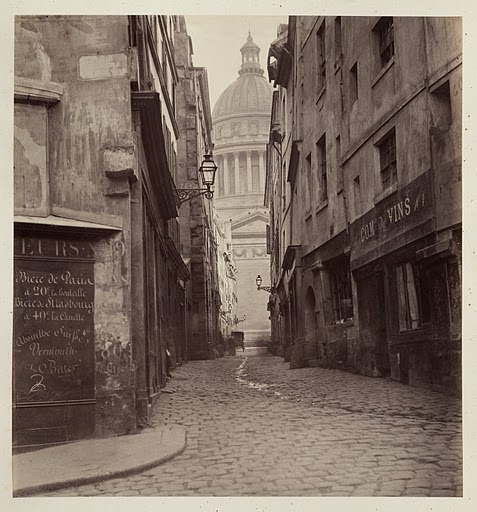

CHARLES MARVILLE, Rue des Sept-Voies de la rue St. Hilaire, ca. 1865, Albumen silver print from wet-collodion-on-glass negative, 11 5/16 x 10 1/2 inches, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Lent by the Troob Family Foundation

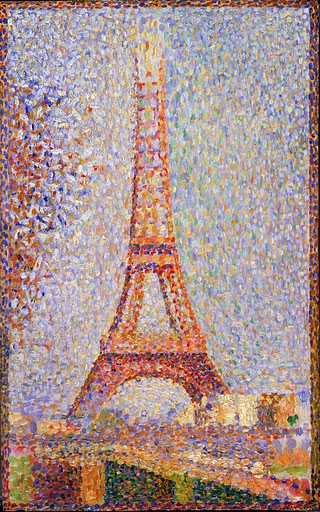

The old Paris was literally decadent, a crumbling city grown larger than but not beyond its Medieval heart. After the War and the Commune, Baron Haussmann's ambitious plan reconfigured the town into the City of Light we know today. Change never came easily; Haussmann had carte blanche, but when Gustave Eiffel proposed an iron tower for the 1889 Exposition, as many artists protested the "insult" to the city's skyline as reveled in the modern statement it made. "Impressionist Paris" goes right up to, and through, 1900, but treats the last decade of the 19th century and the first of the 20th as more the aftermath of the Impressionist era than as the Gay 90s of myth. Here again, the curation plays bait and switch with popular cliché, bringing in the masses with promises of the Usual Suspects but delivering instead a much more surprising and substantial trip through still-recent history.

GEORGES SEURAT, Eiffel Tower, ca. 1889, Oil on panel, 9 1/2 x 6 inches, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, William H. Noble Bequest Fund

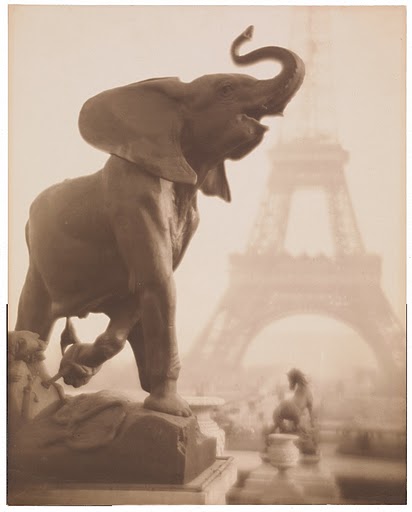

PIERRE DEBREUIL, Eléphantaisie, 1908, Gelatin silver print, 247 x 195 mm (9 3/4 x 7 11/16 in.), Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Prints and Drawings Art Trust Fund

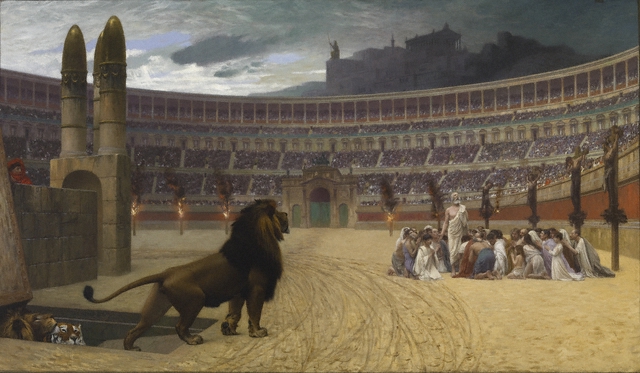

JEAN-LEON GEROME, The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayers, 1863-1883, Oil on canvas, 34 5/8 x 59 1/8 inches, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

A l'autre point de Californie, "The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme" proposed a similarly fuller, and thus revisionist, look at one of the Impressionists' most prominent contemporaries. Although Gérôme was hardly an ally, he, too, ran afoul of the academy before becoming one of its lions. The Getty Museum's survey - which hangs this fall, appropriately enough, in the Musée d'Orsay - rightly presents Gérôme's art as "spectacular;" from the first, the clearly gifted painter was at once a provocateur and a crowd-pleaser, a revolutionary and a reactionary, a guy who could paint anything he wanted, and wanted to paint what would most thrill the public. Gérôme emerged as an Ingres-like portrait painter and, more importantly, as the most prominent among the "Néo-Grecs," rendering subjects, elegant and decadent, that harked back to an imagined, slyly modernized ancient Greece (much as artists across the Channel were painting "Victorians in togas"). From there, the painter's subjects became more luridly anachronistic, vacillating between Roman scenes full of sex and violence (the gladiator scenes crawl almost obscenely with detail) and contemporary figure-landscape scenes in places like Russia and northern Africa.

JEAN-LEON GEROME, Pollice Verso, 1872, Oil on canvas, 38 x 58 3/4 inches, Phoenix Art Museum

JEAN-LEON GEROME, The Serpent Charmer, 1880, Oil on canvas, 33 x 48 1/8 inches, The Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown MA

The allure of the latter location(s) brought Gérôme into his most famous - perhaps infamous - body of work, capitalizing on Orientalisme, the French taste for the "exoticism" of the Middle East and the Maghreb. A century later, Gérôme's depictions of Arab and other eastern and southern Mediterranean peoples would energe from obscurity - and get roundly deconstructed by cultural critics for their depictions of non-Europeans (and colonial subjects) as colorfully dangerous and corrupt. To judge from the selection in "Spectacular Art," Gérôme could be plenty steamy, but was at least as often relatively reportorial, certainly compared with more occasional but more licentious "orientalists" such as Delacroix.

JEAN-LEON GEROME, The Muezzin (Call to Prayer), 1866, Oil on canvas, 39 3/8 x 33 inches, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha

"The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme" was (and I'm sure will remain) a great diversion, silly and fascinating by turns, its pictures gripping you despite yourself and your fits of giggles. Visiting it was like going to a movie (not surprisingly, given Gérôme's profound influence on early cineastes). It did not quite rehabilitate the artist's slick, pandering modality, but the show explained it to the point of acceptability and even delight. As guilty pleasures go, Gérôme is even more high-cholesterol than Impressionism at its most banal. But after the San Francisco shows, Impressionism is that much less guilty a pleasure.