Yesterday's centers are today's outliers. But today's outliers are tomorrow's centers. Who would have thought - from the vantage, at least, of Euro-American superiority - that northern India and various South American cities were vital artistic loci once upon a time? That concept has finally re-entered our thick skulls. Of late we have to consider South Asian art markets and international biennials mounted in Brazil as integral to our present-day artistic discourse (and commerce). So we can certainly grasp the concept of a late-Mughal capital serving as a melting pot of styles and cultures, or the idea of a supposedly peripheral continent producing its own modernist modes and attitudes. Apt, too, that the exhibitions serving to historicize these outlying centers originated in Los Angeles, another once-outlying center preparing (with the Getty's looming "PST") to delve into its own art history.

There was, of course, no overlap between "India's Fabled City: The Art of Courtly Lucknow" at LACMA and MOCA's "Suprasensorial: Experiments in Light, Color, and Space" (both just ended). The kind of art offered in the latter was unimaginable to the artists and patrons populating the former. But the two shows did share one... how to put it? Flavor. The art in both thinks big - not physically big, necessarily, but gesturally big. Color, form, and even function serve to heighten sensation - in very different ways (not to mention contexts), to be sure, and for very different reasons, but to parallel artistic ends. An aesthetic of spectacle pervaded both the late 18th-early 19th century Lucknow court and the mid-20th century South American continent. (The sense of spectacle continues into the handsome, hefty, info-rich catalogues accompanying both shows -- right down to the red and green plastic filters that allow one to read either Spanish or English otherwise illegibly superimposed on each other in the "Suprasensorial" book.)

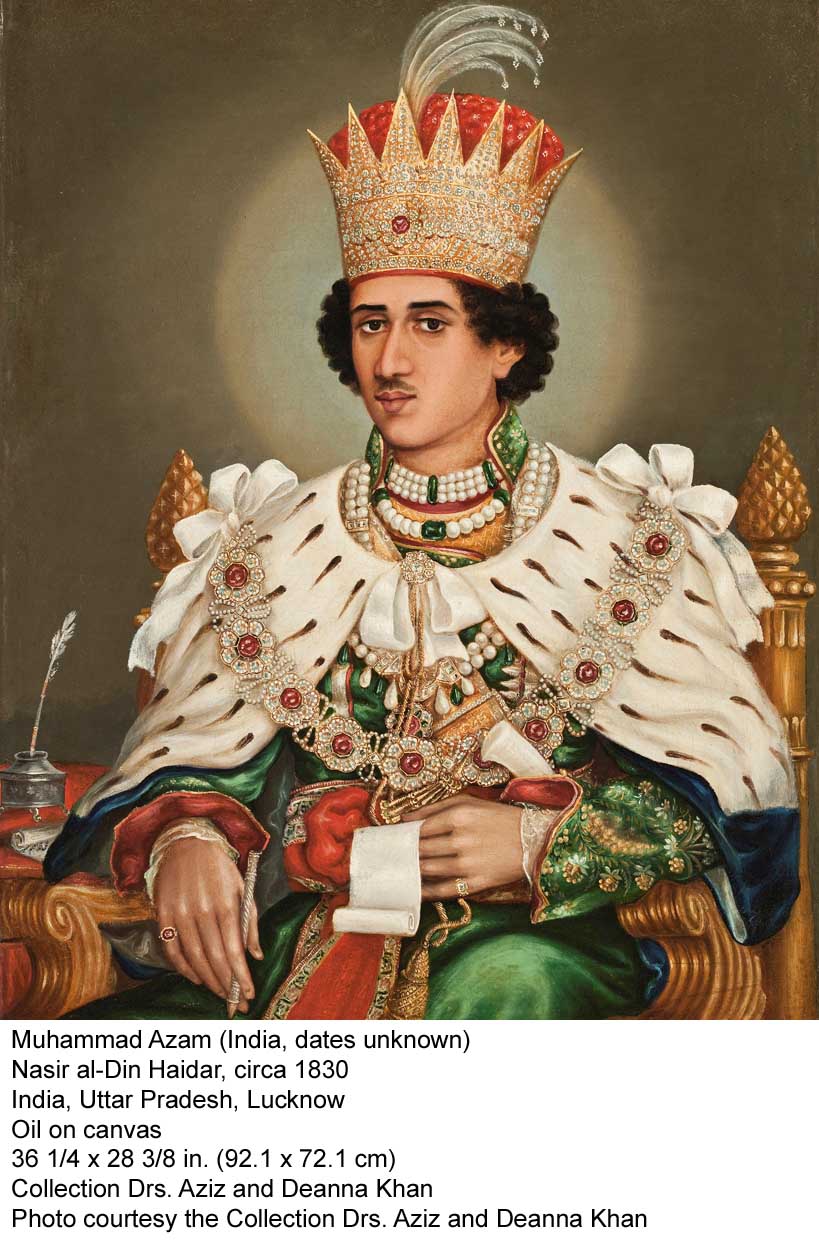

In the case of Lucknow, it was a matter of all sorts of people, from all sorts of places with all sorts of agendas, trying to impress one another into social and political deference, or at least alliance. Lucknow was in fact a provincial Mughal court; but by playing their cards right at a time of unstable politics, the nawabs managed to arrogate a notable degree of independence for their fiefdom. Mughal India was a crossroads of cultures at this time, and in Lucknow the presence of Persians, Indians, and Europeans led not merely to mutual tolerance but to friendly competition, mutual curiosity, and even intermarriage among courtiers, merchants, and the state itself. The art and craft produced for this polyglot, but uniformly wealthy, society of administrators, military men, indigo traders, and other powerful personae - nabobs among the nawabs - was itself highly miscegenated, and "India's Fabled City" brimmed with examples of mutual influence.

The exhibition effervesced with delectable items, and these paintings and manuscripts and tableware and adornment and even photography (documenting life and architecture in the city up to its partial destruction at the hands of the English in the 1850s) can enchant even the most jaded trawlers of museological Asiatica. But what gives this stuff its extra frisson, what puts it over the top, is its hybrid nature, and the broad evidence of influence jumping across civilizations. The Persian-style miniatures, for instance, glowed in this context not only with the typical stylizations we could compare to Western manuscript illumination, but with the intricacies of European naturalism. Conversely, the nawabs' portraits, painted in oils, and the pictorial documents of Lucknow life painted and drawn by European artists, architects, colonial officials, and itinerant visitors, all take on the flatness, clarity, and ceremony native to both Persian and Indian practice. The artifacture featured in the show similarly marries Eastern and Western decorative practice, and the architecture conflates Persian, Indian, and neo-classical characteristics.

Irishmen and Frenchmen were among the most prominent patrons of even Lucknow's most traditional artists, and the Shi'a court was happy to employ the skills of Hindus and Christians. But the center, its own power dependent on the weakness of the later Mughal court, could not hold, and the city ultimately disappeared into British colonial rule. It didn't go without a fight, however - an 1857 "rebellion" that the Queen's Army put down forcefully, raining destruction upon Lucknow's glory. Interestingly, much of the photographic documentation we have of that glory came in the wake of that siege, so we know the place as rubble as much as regal. But Lucknow was real once, a meeting and mixing place of social and cultural practice.

South America, with its rich, if fraught, history of imperialist settlement and subsequent immigration, has been another such meeting and mixing place, a continent whose indigenous peoples all but disappeared into the greed and zeal and pretense of the civilizations that invaded it, and which was for all intents and purposes a cultural outpost of Europe until a good century after political independence. Sound familiar, doesn't it. We won't go into the extra layer of, er, cultural imperialism we blithely imposed on our southern neighbors in the 20th century, but the Second World War gave places like Montevideo and São Paulo a chance to reason artistically for themselves, and to start taking Euro-American modernism and doing their own thing(s) with it. The Latin Americans infused modernist orthodoxy with a spirited, quasi-populist expansiveness (first articulated in Brazil's 1922 "Tropicalismo" manifesto) that sought to embody local customs and styles and natural surroundings. Sounds even more familiar, at least to us Californians.

LUCIO FONTANA, Struttura al neon per la IX Triennale di Milano, 1951 (re-fabricated 2010), Neon, 90 5/8 x 325 5/8 x 263 13/16 inches, Collection Contemporary Art Fundacion "la Caixa," Barcelona, (c) Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milan, Photos: Iwan Baan

And that was the point of "Suprasensorial," which identified a Light & Space movement among artists working in Caracas and Rio and Buenos Aires as early as mid-century - that is, a good decade (or two) before LA's own. The earliest work in the show in fact dates back to 1951. It also was created by an Italian artist for an Italian art exhibition; but Lucio Fontana had been born into the Italian community in Argentina, and his engagement with modernist thought and practice happened on both sides of the Atlantic. With the piece on view Fontana established himself as one of the European avant garde's leading lights - literally: Struttura al neon per la IX Triennale di Milano was the first internationally displayed artwork made of neon. (Czech artists experimented with neon in the 1930s, but their accomplishments weren't seen outside Prague.) And if you're thinking Dan Flavin, think again; Struttura is a drawing in space, a huge, extravagant arabesque looping and coiling above our heads. Originally conceived for an enclosed, darkened room, it got a little lost in MOCA's Geffen hangar, but it still exhilarates - and opened up the room, somatically as well as historically, for the other works in the show.

JULIO LE PARC, Lumiere en mouvement-installation, 1962 (re-fabricated 2010), Painted drywall, mirrors, stainless steel, nylon thread, two spotlights, 509 x 202 x 192 inches, Collection of the artist, Photos: Iwan Baan

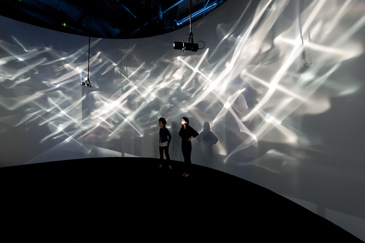

"Suprasensorial" was a sequence of five spaces (all but one re-constructed for this show), two of which were fully enclosed. Being partly open to the Geffen's cold expanse also compromised the impact of the other Argentine piece, Julio Le Parc's Lumière en mouvement-installation, but, also, not fatally. Realized a decade after Fontana's Struttura, Le Parc's brittle, dancing play of reflected light, realized and exhibited in Paris also planted the experimentalist thinking of a young continent in the soil of an old one. So did Venezuelan Carlos Cruz-Diez's Cromosaturación, from around the same time, a grid of rooms each painted in a single color, like a walk-in Mondrian (if Mondrian had permitted himself green), and illuminated with soft fluorescence.

CARLOS CRUZ-DIEZ, Cromosaturacion, 1965 (re-fabricated 2010), Painted drywall, fluorescent lights, colored plastic, 156 x 604 x 291 5/16 inches, Collection of the artist, Paris, Photos: Iwan Baan

Le Parc and Cruz-Diez were doing radical things with light, space, and optics, but only by working outside of home, by importing their space-age "tropicalismo" to the Old World, would they make their mark. And they did - driving home even then the fact that South America was an important breeding ground for the Kinetic and Op Art movements. Cruz Diez's compatriot Jesús Rafael Soto likewise bounced back and forth between Caracas and Paris; he was represented in "Suprasensorial" by Penétrable BBL bleu, a 1999 forest of blue string-like tubing - delightful to lose yourself in and among - that nevertheless represents Soto's experiments with visual interference going back to the '50s.

JESUS RAFAEL SOTO, Penetrable BBL bleu, 1999, PVC tubes and painted metal, 143 4/5 x 157 1/2 x 551 1/5 inches, Collection Helene Soto, Paris, (c) Artists Rights Society, New York and ADAGP, Paris, Photos: Iwan Baan

The one work here originally realized in its home continent dates from the early '70s and plays a whole different game. A conceptual quasi-performance that engaged audience participation even more actively than the other works, Cosmococa - Programa in Progress, CC4 Nocagions , by Rio de Janeiro's Hélio Oiticica (coiner of the term "Suprasensorial") and Neville D'Almeida, invites viewers not simply to walk through but to jump in. And get wet. MOCA presented Cosmococa in all its funky glory, a 20-foot-long swimming pool - replete with lifeguard and changing room - in a darkened space. While you swim (or not), slides project on the walls - this time not abstracted light, but images of John Cage's book Notations (a compendium of composers' scores), often enhanced with lines of cocaine arrayed on the pages. Very early '70s - more potent if considered in light of the oppressive political situation in Brazil at the time. Cosmococa was (thus) the work in "Suprasensorial" that has aged the least well. But how cool is it to do a museum in your bathing suit? How Rio? And how LA, avant la lettre?