Just to catch you up. If you haven't been following the previous installments in this series here goes:

I was singing and talking too much and I got a hemorrhagic lesion on my right vocal cord (just like Adele and Sam Smith). I then had a surgery, which by the end of this ordeal will have left me totally silent, like a Monk (or a tortoise) for five weeks straight. These pieces are my ongoing reflections of the experience.

There's an adage among writers, an admonishment really, that goes like this: "Tell a dream, lose a reader." But not being one to care too much about what "they" say, I'm going to tell a dream anyway.

The months after my dad died, in the fall of 1983, I had these horrible recurring dreams. He'd been struggling for almost five years with stage four lymphoma and the doctors had tried every trick in the book to keep him alive. In the dreams, someone would tell our family about a new treatment that had been discovered and then they'd disinter my father's body and start injecting him with drugs or cut out some different one of his organs. Ghastly stuff, but that's what you get for listening to dreams. This dream though, was only the set-up to the one I really wanted to tell.

Around that time I had a different kind of dream, a dream that was actually one of my happiest moments. When I say that, I mean exactly that. It was one of the happiest moments of my life, including all my waking ones. The dream is so simple I can tell it in one sentence:

I was riding my bike in some western desert, heading toward the ocean.

That's it. The beauty of it however, lies in what I was feeling on that bike, and I dare say, I can recall the feeling perfectly almost anytime I care to.

I was alive then. I was not encumbered by contingencies, nor was I burdened with guilt, or need, or desire. After the cessation of that most painful chapter of my young life, I was suddenly given what I consider to be a clue as to how everything could be better. It was a key to an inner utopia, a hint about how I might choose to live my entire life.

'Drop everything,' the dream said. 'Endeavor to awaken to the miracle of the moment. Be astounded at the ball of fire in an azure sky that's casting light and heat on your face as you move through space. Be cognizant that you are moving through the effort of your own limbs. Limbs fueled by food, which comes from dirt, which is created from disintegrated pieces of mineral, vegetable, and animal matter; food which is brought to your muscles through the vehicle of this mystery called blood. There are white things we call clouds drifting across the sky and they are great and beautiful repositories of water. It's all genius; it's the most beautiful dream imaginable. And now, Peter Himmelman you are free, (as you've always been, but perhaps haven't quite remembered) free to exert your will, free to engage with other people and free to share what you can.'

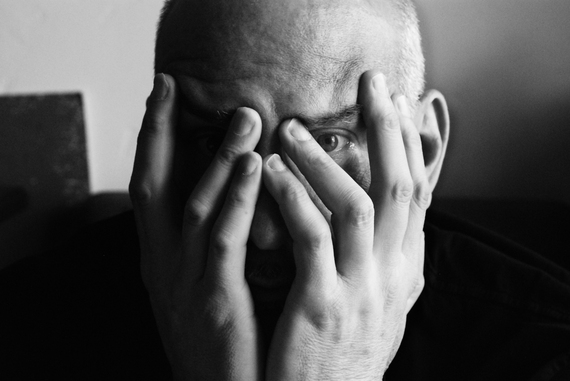

Unfortunately, since it was only a dream, I often make the mistake of thinking that the way I normally feel, the way I typically go through a day, (which is much the opposite of the way I felt in my dream) is what's real and that the dream was, well... that it was just a dream.

But now, in my protracted silence, and in the spaces it has afforded me, I've begun to question that mode of thinking. As I walked down to the bluffs today and saw a row of palm trees, eighty feet tall, and then, the largest body of water in any place known to mankind, and after that, a woman throwing a ball to a brown dog in a dusty vacant lot, I wondered if my constant reverse-alchemy of changing the astonishing into the prosaic is something I wish to continue. In fact, I do not.

Like any tremendously difficult skill, this one takes diligence and an extreme willingness to go against the grain, not only against a culture that insists upon exalting the banal, but in creating a resistance to act against our own primitive drives, (as I mentioned in my last installment) drives which if they had complete sway over us, would tether us to our most base selves.

All one needs is a glimmer of this idea to use as a touchstone. All we need is one experience of it. Perhaps it's when a child of ours is born, or when something profound is taken from us. Perhaps it's when we've returned home after a long absence, or heard a song that brings us to tears.

That being able to see the miraculous in the mundane will never be more than a fleeting notion is obvious. But it should in no way stop us from trying.