The DNA revolution has extended proof of the "traditional" family back to about 4,600 years ago, hundreds of years before Abraham's non-traditional family. New research from a burial site in central Europe confirms that a man, woman, and two young children buried together were a nuclear family -- the boys were the sons of the adults.

The nuclear family discovery is not surprising, since we already had good reason to believe that some people in the Later Stone Age lived in this arrangement. Still, the nuclear family angle drove news reports of the discovery to headline status. The lead researcher was quoted as declaring, "We have established the presence of the classic nuclear family in a prehistoric context."

But it also shows family diversity and respect for a variety of non-biological family relationships. The nuclear-family angle is just one angle of the story.

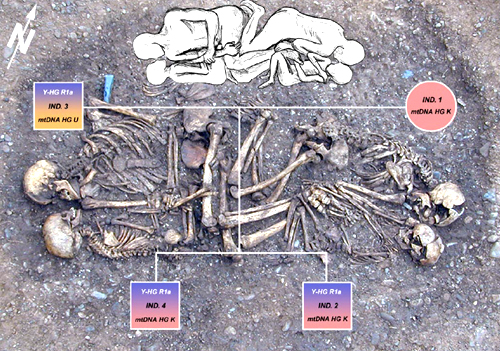

The family is depicted in what is at once a gruesome clinical image and a deeply touching expression of family and community intimacy. The dead family consisted of older adults and younger children, victims of a raid that killed at least 13 people, as the bodies showed signs of violent death despite a desperate struggle to survive. The prime-aged community members apparently returned to find the old and young dead, and buried them according to their familial relations. The mother and father are lying face-to-face with their sons, with their hands intertwined. Digging deeper, so to speak, we find the tender offerings sent off with the dead: stone axes, flint tools, and butchered meat.

Image used with permission of National Academy of Sciences, PNAS.

But instead of just reinforcing our collective sense of the naturalness of the nuclear family -- conveniently including exactly two children (there may have been older children that survived) -- the research tells us a different story about family life, if we let it. That is the story of family diversity. The other graves contained adults and children who were not conclusively their biological offspring -- presumably step-parents, aunts or uncles -- but who were nevertheless buried as families (two with a man and two children; one with a woman and three children; one with a woman with one child).

The burials showed recognition of the different relationships, with only the biological children buried facing their parents. But all the relationships were honored with collective burials. That includes the adult women, who - analysis of bone composition shows -- grew up outside the immediate area, suggesting the practice of exogamy (marrying outside the group) and patrilocality (women moving to their husbands' families).

Those women -- especially the women buried without men -- are what haunt me about the story. It takes a little imagination, but why not think of their life stories as heroic? They "married in" to the community (although the marriage certificates must have decomposed), and cared for their adopted children. They died defending those children, and were lovingly sent off to eternity in graves with those children by their sides.

As long as there have been people, there have been what we now see as families. There are facts to be learned in the study of those families, and the scientific breakthroughs here are truly remarkable. But we tell family stories from our own perspectives. And those of us who respect families as well as family diversity have a good story to tell on this one.