The news is out that Emily has been displaced as the #1 American girl's name. The new top name is Emma, according to the Social Security Administration's database of names for newborn children. Parents interested in the happening names consult this list, along with many others available in the supermarket checkout, online, and so on, to help find just the right name. (Personally, I favor a name that is not that popular -- somewhere between 100 and 400, but shows increasing popularity. That way your kid will be one of the older ones in a growing group of kids with the same name that look up to her -- and you will look like a trendsetter.)

But the reason I follow the name list is what it shows about individual identity. Two centuries ago, the vast majority of European Americans were not looking for a unique name, or a name that was coming into vogue, or a name that matched a popular cultural figure -- or trying to avoid a name that had jumped the shark. They almost always named children after their parents. Besides the sad fact that many children died at young ages -- and that there were too many children to keep track of (the average White woman had 7 children in 1800) -- it just didn't occur to people that children were priceless individuals. And naming wasn't a way to make a statement about character and identity, it was just a family brand.

Under the prevailing Christian wisdom of the 18th century, incidentally, children were born guilty by virtue of original sin, and the main task of parenting was to break their evil spirits and harness their wicked urges. Over the 19th century, as women increasingly were tasked with homemaking and men left home for work, children gradually came to be seen as starting out pure and good, to be nurtured and cared for instead of broken and controlled.

And eventually, in the 20th century, most Americans started to think of each child as unique (and they only had about two per family). Not only was difference valued, but individuality emerged as a project -- starting with naming -- of creating an identity. That doesn't mean everyone wants a unique name (though, unlike in the past, some people do try for that). It means that naming is a statement of the kind of person kids are. So people are influenced by a TV show (Emma was Ross and Rachel's kid), or a political figure (Martin, Malcolm, Barack).

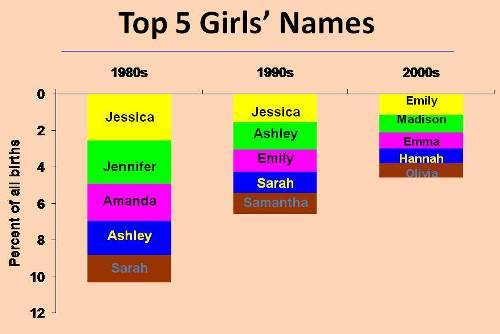

It's not that people aren't conformists anymore, it's that people actively choose their niches, and as a result they have become smaller. Consider the top five names for girls in each of the last five decades. In the 1980s the top five made up more than 10% of all names. Now they are less than 5%. That means there is much less name dominance than there was even two decades ago.

Source: My calculations from the SSA database.

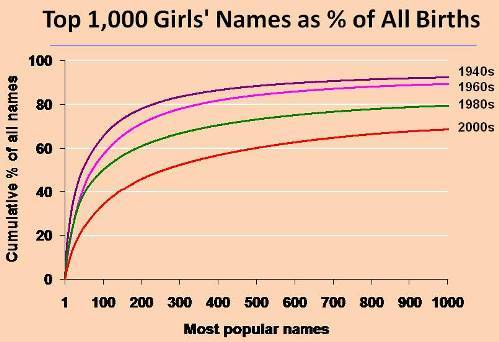

Or look at it over the longer term. In the 1940s, the top 100 names for girls made up almost two-thirds of all names. Now the top 100 account are only about one-third, and you have to add up all the names down to 1,000 before you get to two-thirds. (Note: This is not just about immigration and ethnic diversity: Immigrants were a larger share of the population in 1900 than they are today.)

Source: My calculations from the SSA database.

Mary was the #1 name for 76 years: from 1880 (1st year recorded) to 1946, and 1953-1961 (broken up only by 6 years of Linda). Since then no name has been #1 more than 15 years (Jennifer, 1970-1984). Emily had a chance, from 1996-2007, but her reign ended in time to conform to my theory of increasing diversity over the 20th century.

Another element of this diversity is that lack of staying power for top names. Consider the crash of Hannah, which although still #4 for the 2000s overall, has already fallen down to 17 in 2008. How little loyalty we show. And now a new milestone is approaching, as Mary falls out of the top 100 - she's at 97 for 2008, falling fast from 47 just eight years ago.