Concern and activism over "work-family balance" increasingly focuses on the policy and political bottlenecks that prevent people from successfully caring for themselves and their family members while satisfying their career needs and ambitions. This is an improvement over the self-oriented focus on individual achievement that still drives too much of the discussion on "balance."

The recent book by economist Robert W. Drago, Striking a Balance: Work, Family, Life, provides a crucial focus on inequalities in the care system: between those who receive adequate care and those who do not; between successful professional women who hire careworkers and the poor women who work for them; and between the rich and poor generally. Drago boils down the core work-family policy issues to these four points.

1. Paid family leave

Our inadequate system of family leave serves to widen both gender and race/ethnic inequalities, as recent research shows White women are the most likely to benefit from current leave policies. Unfortunately, parental leaves usually are taken by women, and associating women with carework weakens their negotiating power within families. So leave policy has to be coupled with policies that promote gender equality or it may make matters worse in other ways.

2. Early childhood education and childcare financing

The U.S. childcare situation is depressingly stagnant. Census Bureau data comparing 2005 with 1985 shows fathers' contribution as primary care providers is virtually unchanged. In fact, grandparents now surpass fathers as primary care providers.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau data.

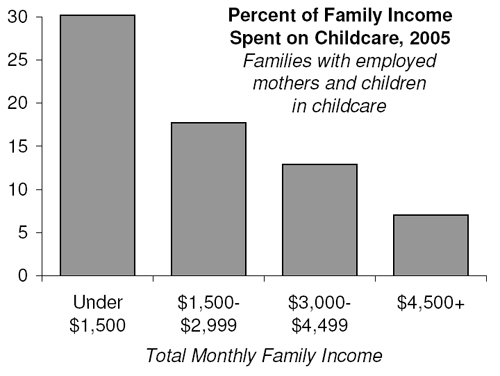

Clearly, the lack of reliable, affordable childcare widens inequality for families, as poor families with employed mothers spend more than a quarter of their income on childcare. Further, a recent study finds that almost one-third of urban mothers of young children see their childcare arrangement fall through in a given month. Almost half of those women miss work as a result, and half of those miss work repeatedly in the search for reliable affordable childcare. As hard as it is for everyone to find the right childcare arrangement, the consequences of our inadequate system for poor families severely threaten their health, well-being and development, not just their mothers' sense of family balance.

3. Guaranteed health insurance

We now know that welfare reform - moving millions of mothers "from welfare to work" (or at least "from welfare") - has resulted in many poor families losing their health insurance. Employer-based insurance, SCHIP, and Medicaid have not kept up with the loss of insurance that families experienced when they were booted from the welfare system. Overall, about one-quarter to one-half of former welfare recipients are without health insurance. A recent study in Oregon, which has one of the most generous programs of providing health insurance to the poor, found that about 11 percent had no health insurance half a year after leaving welfare.

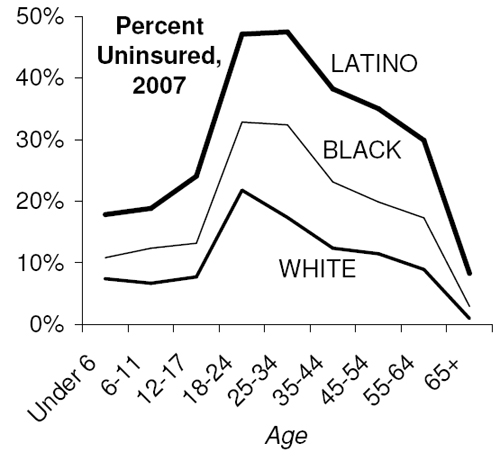

The Oregon study found a disproportionate share of Latino families without health insurance after leaving welfare. This fits with the most recent national Census data (see figure), which shows huge racial/ethnic gaps in the proportions of people uninsured. Latinos are twice as likely as Whites to be uninsured, and Blacks are in between. Children are more likely to be covered (because of government health plans) than young adults, but even among children Latinos are more than twice as likely as Whites to be without insurance.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau data.

4. A minimum wage that lifts people out of poverty

When paid work doesn't cover the costs of living, people are forced to make impossible tradeoffs between working for too little to pay for care and working for nothing to provide care. Drago argues that a living-wage minimum wage (indexed to inflation to prevent political gridlock over raises), will increase the capacity of poor workers to care for their families by allowing them to work fewer hours. We need this unpaid work, since the market doesn't provide the care we need at an affordable cost.

This new research reminds us that "work-family balance" is critical because so much of our care comes from our families. The market-based system of seeking and providing care means that those with less market power shoulder the burdens of carework - low-paid and unpaid - that make all work possible. People may struggle for their own work-family balance, but without a comparable balance in government policies the supports for success in that struggle will not stand.