This past weekend I sat immersed in Rabbi Avi Weiss' newest book, "Open Up The Iron Door: Memoirs of a Soviet Jewry Activist." This memoir (to be published March 2015, Toby Press) sheds a tremendous light on the formation of this both humble servant and ferocious defender of his people. A person who I have been blessed to call my teacher and mentor for the past decade. As you read this book you are transported back to the epic struggle to free the three million Russian Jews locked behind the Iron Curtain of the Soviet Union. As you journey through the almost unbelievable stories of resilience and courage you come to ask yourself some fundamental questions about Rabbi Weiss:

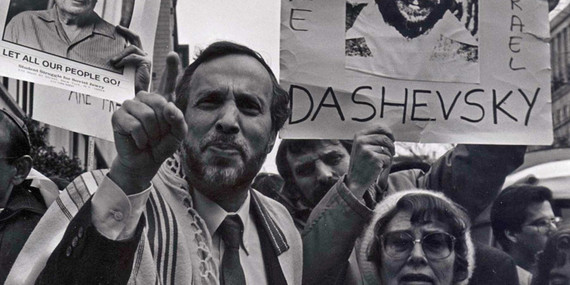

How did a Yeshiva University rabbinical student and a pulpit rabbi first in St. Louis then in Monsey, New York and finally in the Bronx neighborhood of Riverdale end up having a career in social action that would cause him to be arrested in acts of civil disobedience more than 50 times? What led this young rabbi to stage a sit in protest in the office of the US Ambassador to the UN, George H.W. Bush? To take over the office of Aeroflot offering to pay for the flights of the millions of Jews locked behind the Soviet Iron Curtain? How did he navigate both acting outside the establishment American Jewish institutions and agitating those same organizations to become more involved and to take a stand?

Most powerfully, what would lead a group of young rabbis and students locked in solidarity with oppressed inmates in Soviet prisons and work camps to believe that they could topple the will of the Soviet Union? That their demonstrations, acts of civil disobedience and their voices shouting "1-2-3-4 Open Up The Iron Door!" would be heard in the upper echelons of the Kremlin and change the fate of three million Russian Jews only a few short decades after the Holocaust?

To gain a glimpse of the answers to those questions is to gain depth in what is needed nowadays in the field of Jewish social justice and activism. Rabbi Weiss quotes the pivotal early Zionist thinker Ahad HaAm's well known line, "more than the Jews have kept the Sabbath, the Sabbath has kept the Jews" and offers the thought that more than American Jews impacted Soviet Jewry, Soviet Jews impacted American Jewry. The struggle to liberate the millions of Jews denied their identity in the Soviet Union gave the American Jewish community a connection to the collective family of Israel. If, for example, Boris Kuchubiyevsky living in the Soviet Union facing the prospect of years of hard labor or worse could say the following quote publicly what about the attachment of Jews living in the United States in freedom and comfort to their people and to their destiny:

"As long as I live, as long as I am capable of feeling, I will do all I can to leave for Israel. And if you find it possible to sentence me for it, all the same. If I live till my release, I will be prepared to go to the homeland of my ancestors, even if it means going on foot."

The determination of Russian Jews to stand up for what they believed against all odds, to face the harshest and most brutal punishments and to still have the courage to defy the mighty Soviet machine, was like a bolt of energy to an American Jewish community that was increasingly becoming unmoored from its sense of collective responsibility.

The most profound outcome of cultivating this reservoir of attachment to one's community and to the narrative of one's people is that instead of becoming increasingly inward focused, that sense of justice can extend to the wider world. To say one has love for the entire world is meaningless until one can genuinely say they have love first for themselves and then growing out to their family, their community, their nation and then all humanity. This was a lesson taught to me by Rabbi Weiss while I was still a rabbinical student. It comes from a lifetime of activism based on the premise that when one begins from the inner circles of relationship and works their way out their activism is rooted and impactful.

The field of Jewish social justice in this country and elsewhere is thankfully large and diverse. Jews of all ages and backgrounds are drawn to either work professionally or volunteer for social justice causes. Many large American cities have their own Jewish social justice organizations that are joined by national organizations working on a myriad of issues; immigration, gun violence prevention, economic injustice, worker rights and more. In 2015 it is possible to graduate college and begin a career in Jewish social justice and feel secure in that professional choice.

This memoir should be mandatory reading for every person entering the field. This memoir should be mandatory reading for every Jew, young and old, who decides to dedicate time either professionally or as a volunteer to working on issues of justice. A comprehensive curriculum should be created based on this book in order to impress upon each and every person in the Jewish social justice arena in the 21st century that not only is it possible to work towards making the world a better place from a deep attachment to the Jewish people and to Jewish tradition but it is the ideal way to do so. Unfortunately, what we see today all too often is that in the quest to be ever more open to work with all sorts of allies and partners and to be ever more inclusive of all sorts of support, Jewish social justice organizations put topics like "Israel," "anti-Semitism" or "Jewish peoplehood" in folders tucked deeply in the file cabinet not to be opened for fear of offending someone.

At the end of the memoir Rabbi Weiss makes us focus on the fact that there is still "ample amounts of injustice for our children and grandchildren to take on, both within our communities and around the world. As we are reminded in that rabbinic book of wisdom, Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers), it is not our obligation to complete the task, but neither are we free to desist from beginning the effort; we must do everything in our power to perfect the world in the brief time we are allotted on this earth."

It is clear that Rabbi Weiss continues to do everything in his power to perfect the world emanating from a deep particularistic love for his people and through that particularism a love for the entire world. May we strive to emulate that model.