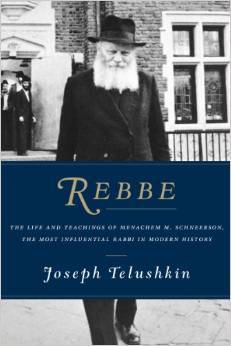

Rabbi Joseph Telushkin is one of the great Jewish thinkers of our time. In addition to being a prolific author -- the Rabbi has published over 15 books running the gamut on Jewish topics, from history to ethics -- and a dynamic speaker, Rabbi Telushkin is a thoughtful scholar. I was thrilled and intrigued to see that his newest work would take on the important topic of the life of Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe. While the project could have easily succumbed to the realm of hagiography, thankfully Rabbi Telushkin's work goes beyond the usual biographical form and delivers a rich tapestry of a dynamic and complex man. And like a tapestry, there are many threads in this book, all of which lend themselves to a story worth telling.

At over five hundred pages in length, Rebbe (Harper Wave, an imprint of Harper Collins) is filled with important stories. With this work, Telushkin has altered the paradigm of the of rabbinic biography. While historical accounts of long-forgotten or obscure Jewish sages can often come off as dry and without meaning, while rabbinic accounts tend to exaggerate virtue for the sake of obedience, offering only censored and incomplete accounts, I found myself deeply trusting in Telushkin's charitable yet honest account of Rabbi Schneerson. In Telushkin's hands, "the Rebbe" emerges not as an abstract figure from yesteryear, but rather as someone whose influence still remains relevant two decades after his passing.

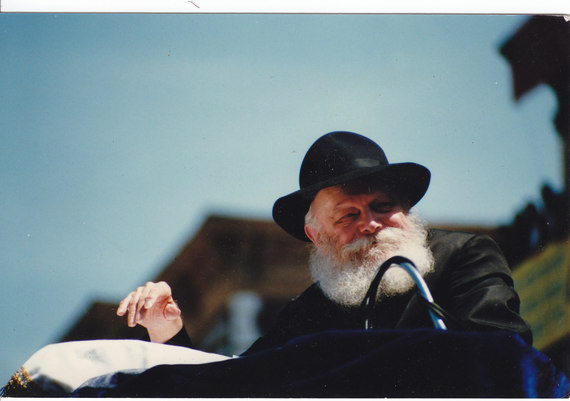

Rabbi Schneerson reverently referred to as "the Rebbe" both inside and outside Chabad-Lubavitch circles, was one of the most influential Jewish leaders of the twentieth century (Telushkin unabashedly suggests that he was the "most influential rabbi in modern history" in his subtitle for the book). Rabbi Schneerson defined and modeled pious Jewish living for decades, going to so far as to have influence on the non-Jewish American consciousness. Newsweek even went so far as to label the Rebbe "the most influential Jew in the world." Although he never sought the position of Rebbe (even going so far as to protest the international campaign for his candidacy) and was initially known to be an introvert, Schneerson quickly became a global ambassador for Judaism when he expanded an obscure group of Hasidic Jews to an international powerhouse of outreach and education. Fast forward several decades and the Chabad-Lubavitch global influence reaches far beyond that of any other Jewish institution in history.

How did this happen? Through his clear and unambiguous prose cultivated from many sources, Telushkin recounts how the Rebbe fundamentally transformed notions of human potential, as he believed individuals were capable of much more than we imagine for ourselves. The dynamic narrative is time-bound yet not chronological. Indeed, if one were to pick up this book without knowing a single thing about Rabbi Schneerson, he/she would first be introduced to a man who was consulted by members of Congress, was honored by presidents, all the while engaging in his clerical duties. The amount of time he spent on and with others is staggering. Personally, I am baffled at how he could sleep so little, literally almost not at all, yet still have the energy and stamina to dedicate so much time to others throughout the day and night. It was in this milieu where his work has had lasting impact. Perhaps the Rebbe's greatest legacy, if one could define it succinctly, was his eagerness to embrace all Jews regardless of their religious commitment, something many Jewish sects did not do, indeed continue to ignore at their loss.

What Telushkin conveys best is how generous the Rebbe was with his time, In addition to building (or rebuilding, depending on one's point of view) a sustainable movement, teaching, writing, supervising, and in engaging in voluminous correspondence, the Rebbe spent countless hours in compassionate one-on-one personal consultations (called yechidus) that would go on throughout the night. From his modest office came the pronouncements of a new way of Jewish life in America. The Rebbe was an intellectual, a spiritual giant, who literally took the world upon his shoulders from his humble compound at 770 Eastern Parkway in Crown Heights, Brooklyn.

The fruit of these labors are still being cultivated. As a matter of course, the Rebbe would send emissaries to work in places where Jewish communities were struggling or non-existent. (There are many instances within the book of how many people chosen to be emissaries, called shlichim, were reluctant to embark on their assignments.) Today there are Chabad houses in forty-eight states and in eighty countries run by over four thousand tireless Chabad couples and their families. Like many people, I first experienced Chabad as a freshman in college, which it made it all the more interesting to learn that the Rebbe, a graduate of esteemed European universities, was opposed to his followers going into higher education. Now, it seems almost counterintuitive that a Rabbi would be against modes of learning, but the entry point for many young people's first Jewish experience comes through Chabad campuses at colleges all across the country. Indeed, I joined learning sessions, Shabbat meals with niggunim (wordless melodies), and fabrengens (celebratory soulful learning sessions with much imbibing and good cheer) with dozens of these emissaries around the globe, and their generosity is unmatched.

The Rebbe's outreach did not stop with young people; no one was off his radar. The Aleph Institute, a Chabad-affiliated organization, reaches out to the thousands of Jews in prison and helps these individuals maintain observance and tradition, thus carrying out the Rebbe's belief that the movement should reach every Jew in the world, free and not free.

Telushkin quotes Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, the former Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom, who writes:

Among the very greatest Jewish leaders of the past, there were some who transformed communities. There were others who raised up many disciples; there were yet others who left us codes and commentaries which will be studied for all time. But there have been few in the entire history of one of the oldest peoples in the world who in one lifetime made their influence felt throughout the entire Jewish world...the Rebbe was one of the immortals.

Telushkin's book is, like his previous works, remarkably well researched and historically grounded. He focuses mostly on the leadership and teachings of the Rebbe, as well as his interaction with multitudes of people from all walks of life, thereby making most of the Rebbe's core values tangible to readers. In taking this approach, Telushkin decisively reconfirms Rabbi Sacks' belief.

Reading this book has made me a better person, just as it made the author better. Telushkin relates in the introduction: "I am a happier and more spiritual person as a result of writing this book -- and I would like to believe more generous and less judgmental of others." While Telushkin is an Orthodox rabbi, he is not a member of Chabad. This lends to the gravity of this biography. It makes his chosen subtitle all the more relevant and this alternate perspective adds depth and flavor:

I entered into writing this book with a high regard for the Rebbe... and I came out with an even higher one. Along the way, I learned that one can have great admiration for a person with whom one has profound disagreements.

Indeed, the Rebbe's life and work remains consequential to contemporary Jews, both observant and not; even non-Jews should feel welcome in learning about the Rebbe's teachings. The concepts rooted in the Rebbe's educational philosophies are deeply intertwined with his life experiences and the book makes this apparent very early within its biographical framework. Although his teachings are manifold, after reading the book I came away with new perspectives about how the Rebbe operated and how he organized his epistemological views of human interaction with the world:

•Now is the time -- This stems from the Rebbe's insistence that good actions should not be delayed but be done immediately. The Rebbe tirelessly focused on optimism (on simcha shel mitzvah, the joy of serving and not dwelling on sacrifice and loss) and optimistic language (Consider that he would not use the phrase beit cholim for hospital since he did not believe it was uplifting or generative to be called a house of the sick. So instead he replaced it with beit refuah [house of healing]. Further, Telushkin found that "a perusal of forty years of the Rebbe's lectures reveals that he did not criticize people by name."). Some other examples of the Rebbe's optimism can be seen in his usage of the Yiddish phrases, "Tracht gut un vet zein gut" (think good and it will be good) and his replacement of S'iz shver tzu zein a Yid (it's hard to be a Jew) with S'iz gut tzu zein a Yid (it's good to be a Jew).

•Respect for Others -- The Rebbe inherently believed that there is no such thing as kiruv rechokim (bringing an unaffiliated Jew closer to God). He once said, "We cannot label anyone as being 'far.' Who are we to determine who is far and who is near? They are all close to God." We should not judge another but love and embrace them unconditionally.

•Empowerment -- Rabbi Sacks wrote: "I had been told that the Rebbe was a man with thousands of followers. After I met him, I understand the opposite was the case. A good leader creates followers. A great leader creates leaders. More than the Rebbe was a leader, he created leadership in others." Telushkin's biography captures countless examples of how the Rebbe empowered so many people around the world, from all walk of life. No matter if the person was a chess prodigy or a shoemaker, the Rebbe would treat everyone with respect and dignity. This is the most effective means to engage and learn from others.

Telushkin intimately captures the Rebbe's faith, the way he lived his Judaism with pride, not fear, and inspired others to do the same all while remaining exceedingly humble, Through his deeds, the Rebbe's life exemplified ultimate humility. He nullified his own wishes and ego to completely serve God, but in doing so, he placed his temporal faith in people. The Rebbe once said, "Without love of Torah and love of one's fellow Jew, the love of God...will not endure."

Although the Rebbe's wife, Chaya Mushka, is mentioned throughout the book, it is mostly in sketches. This is probably deliberate though, because she was an extraordinary woman who requires an entire book to herself. Some of the Rebbe's greatest lessons stemmed from his belief in existing in the moment. When a Jew does a mitzvah, a commandment, he/she is like the holiest person in the world, regardless of what they did right before or what they will do right after; Telushkin conveys this plainly mainly places throughout this work. Leadership is about going where no one else is already serving. To take charge in the places unknown is have spiritual courage (not incidentally, one of my highest ideals). Further, the Rebbe urged us to take responsibility. Schneerson once said: "Before you go asking others (what to do), first listen to what you have to say about it - sometimes your own advice is the best advice."

Just as I grew in my own development as a Jew from what Chabad offers so brilliantly and warmly, many others who may disagree with certain ideologies have also benefited greatly. Among leading Jewish voices today who were taught and nurtured in the Chabad system and went on to their own personal platforms are Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, Rabbi Shmuley Boteach (and by extension Senator Cory Booker of New Jersey,), Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach (of blessed memory), Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, and Matisyahu.

Because it could not be avoided, Rabbi Telushkin goes to great lengths to redeem the movement that many have written off as extreme and dangerous, oftentimes due to the belief of some that the Rebbe was the Messiah. While he shows that this is a minority camp, Telushkin also demonstrates textually how there are two different types of Messiah (the actual and a potential). A "presumed Messiah" ("chezkat moshiach") strengthens the Jewish people so significantly that they represent, while still alive, the potential for redemption. Only time will tell if God will choose an individual, during their lifetime, for the ultimate redemption. If one believes in a personal messiah, one would have been hard pressed to find a more capable and possible candidate as a Rebbe during his lifetime.

As much as I admire Rabbi Schneerson, there is also much room to have profound disagreements with him. As a Modern Orthodox Rabbi, a religious pluralist, and a social justice activist, there were times during the book where issues came up where I could not reconcile them to my own view of Jewish beliefs. These aren't petty issues either: the role of public Jewish activism, separation of religion-state, centrality of messianism, adoption, conversion, Israeli politics, etc.

Yet, while there are issues that I personally disagree strongly with the Rebbe's ideology I felt such a deep love and admiration for this great man who did so much for the Jewish people. The Rebbe's impact will be felt for centuries and for good reason. Even Jews with the slightest interest in Chasidic theology should enjoy this book. What Telushkin has done is remarkable. On the twentieth anniversary of his passing, Rabbi Schneerson's leadership, commitment to loving and helping others, and very public demonstration of Jewish values and ideals should be honored. Rabbi Telushkin's work does just that, a testament to a life fully lived. Let us hope that all those who read Rebbe embrace at least a small part of the values and principles that Rabbi Schneerson espoused. This is a much welcome addition to the Telushkin canon and one that will be a staple of rabbinic biography for years come.

_____________

Rabbi Dr. Shmuly Yanklowitz is the Executive Director of the Valley Beit Midrash, the Founder & President of Uri L'Tzedek, the Founder and CEO of The Shamayim V'Aretz Institute and the author of five books on Jewish ethics. Newsweek named Rav Shmuly one of the top 50 rabbis in America."