Last Tuesday, amidst the drone of a taxiing airplane and the cacophony of half a dozen squealing infants, I tucked into my free copy of The Economist. Air Canada Flight 856 westbound from my former home, London, was delivering me to Toronto after an epicurean week's worth of art delectation. I felt some kind of latent nationalistic need to read one of Britain's most respected publications when I selected the magazine and it turned out to be an auspicious and informative choice.

Much to my delight, sandwiched between articles on former first lady Hillary Clinton's actions as Obama's secretary of state and Apple's stock value in plebeian terms was "un petit mot" on Damien Hirst's forthcoming Tate Modern blockbuster exhibit. I was rather disappointed to miss Hirst's show by a mere eight days and wondered if Tate Director Nick Serota's selection of work could have ameliorated my opinion of Britain's po' boy-turned-global brand. More insistent, however, was my anticipation of how London's more serious art critics would react to the show and the conclusions they would ultimately draw.

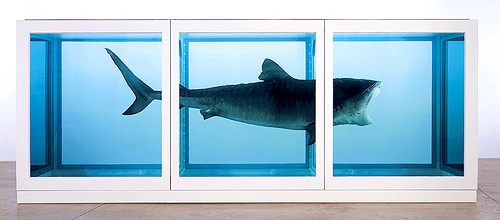

The Economist article's headline, "Is nothing sacred?", is an apt sentiment with which to begin considering Mr. Hirst's sanctimonious position within today's art market. Described recently by Observer art critic Sean O'Hagan as a "mouthy, working-class lad from Leeds, with hooligan tendencies," (1) much of the artist's audience regards him as a phenom who successfully exfoliated his humble skin to reveal a diamond underneath. Or at least a man with many diamonds' worth in his pockets. Is the value of art within its 21st-century constitution contingent on auction hammer price or meaningful cultural currency? Put simply, it continues to be questionable whether net worth is equivalent to critical and artistic worth. As the anonymous Economist writer points out, wealth notwithstanding, Hirst has not, until now, been offered a solo retrospective at a modern art museum.

A toss in the face of Hirst-dom is the fact that of the 67 artworks borrowed for his spring retrospective (the Tate partially owns six pieces), only three have come from public institutions. Dismissal from the public sector signifies doubt in the longevity of an artist's relevance to me. The bulk of the show has been loaned by private collectors the likes of Miuccia Prada, Bernard Arnault, and Steve Cohen. Aren't they glad that their property has been "anointed" by the Tate, raising the resale value exponentially? Smart move, Miuccia. Hirst's art is nearly exclusively discussed within the context of money and secondary market value, a trend to which The Economist article adheres. The fact that every visually analytical talking point is undermined by a comment on the asking price or ownership of that specific piece of art makes Hirst's conceptual and artistic worth rather dubious. Heck, the artist himself lent "A Thousand Years" (1999) to the Tate after buying it back from art business mogul Charles Saatchi in 2003. When an artist re-collects his own work, is he successfully inflating his market value or reclaiming something he deems meaningful?

The critic's agenda begins to turn opaque with the proclamation of "Mr. Hirst's ability to transform dry conceptual art into witty, emotionally engaging work." (2) The implication here seems to be that the 73 works on display will convince visitors of the artist's progression from tedious, immature assemblages to poised, intellectually thoughtful artwork. Having attended Mr. Hirst's recent exhibitions at the Wallace Collection (No Love Lost) and White Cube (Nothing Matters) in addition to this year's foray of dots splattered across canvas at Britannia Street's Gagosian Gallery, I can't conjure which body of work might have precipitated such a celebratory reaction from a critic. Let the reader be pre-warned that there are no figurative paintings included in the Tate exhibition. Could it be because Hirst received vehement criticism for his insulting appropriation of British darling Francis Bacon's style, themes, and subject? The omission of any material from the two above-mentioned London shows is surely indicative that Hirst's recent practice is anything BUT witty or emotionally engaging.

For those who are unfamiliar with the Tate Modern, the slanted descent into the gallery's Turbine Hall finds you questioning whether you are on the ominous path to Hades or are being granted access to some covert, sanctified crypt. The Hall has been host to artists of a startling calibre: Doris Salcedo and Ai Weiwei, among others. It is in this vacuous, "post-industrial cathedral for art" that Hirst's "For the Love of God" (2007), will be spot-lit in a dark room. The skull-shaped sculpture of real human teeth and millions of dollars worth of diamonds is, apparently, a comment on what the Economist calls "belief system of capitalism." Its dramatic spot-lit installation smacks less of a dialogue with today's socio-economic state, however, than it attempts equation with the Crown Jewels in the Tower of London. When compared to Turbine Hall's inaugural installation -- Louise Bourgeois' poignant and breathtakingly majestic steel spider, "Maman" (1999),"For the Love of God" is crass and sacrilegious. It is nearly impossible to engage emotionally with a £50m sculpture that failed to sell.

Stepping off the plane into Toronto's frigid air, I came to the same conclusion I always do after reading about or seeing Damien Hirst's artwork: I am astonished that our fickle art world has allowed him gracious passage for over 20 years. Hirst's ability to transform himself into a branded personality is not novel, nor are his indulgent means of artistic creation. Finally, the fact that his retrospective is unable to travel to Los Angeles' Museum of Contemporary Art as intended because transportation and installation would exceed the museum's entire annual exhibition budget is absurd and maddening. Hirst should not be remembered for dissolving the border between the sacred and the profane, as The Economist critic has asserted. He should be scolded for flooding the current art market with overpriced, meaningless works of art that will inevitably be a permanent thorn in the wing of art's history.

Damien Hirst's mid-career retrospective runs from 4 April - 9 September at the Tate Modern, London.

(1) Sean O'Hagan, "Damien Hirst: 'I still believe art is more powerful than money'", The Observer, (Sunday 11 March 2012): 10

(2) "Damien Hirst Retrospective: Is Nothing Sacred?", Books and Arts, The Economist, (March 24-30, 2012): 92

Image credits in order of appearance:

Damien Hirst's "The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living" (1991), Courtesy of Tate Gallery, London

Damien Hirst's "For the Love of God" (2007), Courtesy Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Louise Bourgeois' "Maman" (1999), Courtesy of Tate Gallery, London