Photographer Jeff Brouws, whose book, Approaching Nowhere, has been a touchstone for photographers and those interested in the New Topographics Movement, has been photographing and studying the plight of America's inner cities for the past 15 years. Brouws' inner-city images acutely document the economic, social and environmental transition that has taken place in the years that have passed since America's manufacturing peak.

What we now seem to have in many of our inner cities is a largely forgotten population of people, attempting to eke out an existence in a neglected environment. Addressing this issue, Brouws states:

Many urban areas were red-lined; no bank would loan money to buy businesses or homes, and no insurance company would insure the property. Because of these discriminatory practices it was harder for African-Americans to get mortgages or borrow capital to start businesses. This negative impact of redlining affected upkeep -- absentee landlords who saw real estate values plummet due to red-lining wouldn't bother to maintain their properties. So began the long, slow decline of inner-city America, a location filled with minority residents who lived in substandard dwellings, endured declining employment opportunities and faced severe housing shortages.

Discarded Landscape # 35, Detroit, Michigan

Discarded Landscape #1, Ravenswood neighborhood, Detroit, Michigan

The sad thing is that "poverty" and "the impoverished" are not sexy buzz terms this election season, nor have they been in the last few presidential contests. The modus operandi seems to now be out-of-sight-out-of-mind for much of this struggling inner city-based population. Our government's reaction to this? Poorly thought out sloganeering that may sound fine to some, but is a bitter pill to swallow in the context of the Jeff Brouws photograph below. Brouws spoke about this very thing in relation to his photos:

Here's a neighborhood scene in Detroit that represents the disparity of how tax dollars are spent in cities and suburbs. By the way, suburbs usually get the lion's share of federal subsidy. You'll also recall Bush's infamous Leave No Child Behind program, public policy reduced to a slogan. Revenue for education is directly derived from local tax bases. In the inner city with its low-income population, depressed property values and little to almost non-existent manufacturing or commercial activity there isn't much of a tax base.

Leave No Child Behind, Chene and Canfield Streets, Detroit, Michigan

Over the past few decades, our urban centers' solutions to inner-city housing have been problematic. Many cities erected low-income housing, such the Robert Taylor Homes shown in the Jeff Brouws photo below. Equivalents in cities like Pittsburgh and Baltimore became crime- and drug-infested hellholes that, finally, after years of deterioration, were imploded or ripped down.

Robert Taylor Homes (since demolished), Chicago, Illinois

Brouws provided this insight into this low-income public housing issue:

One of the solutions to the inner-city housing problem, or so thought the government, was to erect public housing, like the Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago. This was low-income public housing based on Le Corbusier's Radiant City concepts. These concepts, when interpreted by city planners in the 1940s and '50s to house the urban poor, produced results that were the opposite of his intentions: the high rises were horrible and dangerous places to live.

Social engineering factored into freeway construction in metropolitan areas during the 1950s also. The freeway, by its mere creation, became a barrier to cordon off one part of the city from the other. Freeways also played a key role in urban renewal: Many slum areas in cities (usually housing the urban poor) were systematically chosen as the pathways for the new interstate system. This in turn also fueled inner-city housing shortages, which further enhanced white flight to new homes in suburbia.

All of these things have helped make our inner-city denizens something akin to a disappeared population, whose voice is rarely heard and whose concerns are rarely recognized. There are pockets of hope in these areas, with people doing there best with what's left: sustainable garden areas and green zones; art displays; and even inner-city farming are some of the activities we are now seeing in these once forlorn vacant lots and neglected stretches. But it's nearly a new frontier sprouting from the old in these city neighborhoods, and the positive factors are still outnumbered by the negative. The new ideas being implemented will need help to truly become game-changers, but first the problems, as well as the solutions, must be recognized by a larger contingent and then fostered.

As it stands now, the condition shown and described in the Jeff Brouws photo below remains too commonplace.

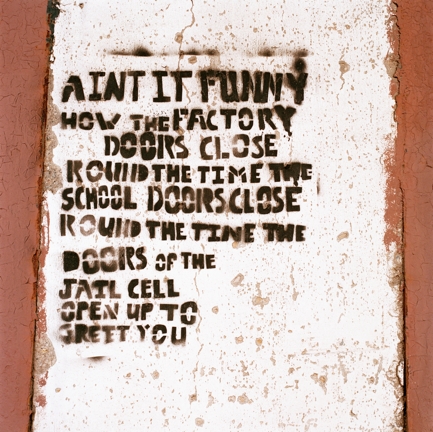

Ain't It Funny, Detroit, Michigan

Sometimes inner city environments are the only places in America where you see political expression. The language in this image expresses a societal denial; these landscapes of chronic poverty and racial segregation are places that don't register in the consciousness of most Americans as I said earlier. Inner city inhabitants feel invisible and forgotten. Foreigners are often shocked to learn that the USA -- a country filled with so much abundance -- has 15% of its population living below the poverty line; that number is 20% in Washington DC.

This graffiti concisely expresses the social realities of inner-city life its inhabitants know only too well:

Ain't it funny

how the factory

doors close

round the time the

school doors close

round the time the

doors of the

jail cell

open up to

greet you

More of Jeff Brouws' work and a full interview I conducted with him can be found at American Elegy. Additional information about Jeff Brouws can be found at his website.

Randy Fox is the creator and administrator of American Elegy. A selection of his Rust Belt photography can be found here.