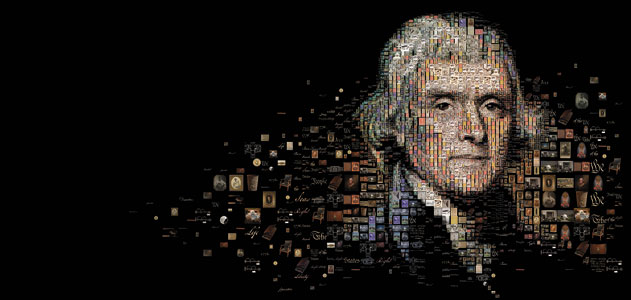

*Image by Charis Tsevis, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2012

Thomas Jefferson is known as a true innovator in American history. He authored the Declaration of Independence, brokered the Louisiana Purchase, and was a principal advocate for religious freedom in the early days of our republic. However, the magnitude of Jefferson's political accomplishments often overshadow another important aspect of Jefferson's legacy. The sheer range and depth of Jefferson's intellectual pursuits also distinguish him as one of America's most accomplished innovators. How did Jefferson innovate, and what can today's leaders do to apply his brand of ingenuity in the Information Age? Deconstructing Jefferson's life reveals an intriguing mosaic of science, the arts, and cultural understanding, all of which contributed to a unique brand of statecraft that was unparalleled in his time.

Thomas Jefferson and Science

Of all the intellectual disciplines available to him, Thomas Jefferson held science in the highest regard. Jefferson cultivated his capacity for scientific reasoning at an early age. As an enlightenment thinker, Jefferson believed that the physical world was defined by natural laws, and that a systematic form of reasoning could be applied to understand these laws. He regularly studied the works of individuals like John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton, enlightenment thinkers who dedicated their lives to balancing the intellectual faculties of reason, science, and philosophy.

Naturally, being the son of a pioneer and surveyor endowed him with a predisposition for understanding the science of measurement. Jefferson had a genuine love for scientific instruments, and regularly collected mathematical and astronomical devices.

*Orrery similar to the one owned by Jefferson. An orrery is a device used for modeling orbital orientation of the planets (from monticello.org collection)

Jefferson was also among the first in the American colonies to conduct study in the discipline of meteorology (1). He began making records of weather patterns while studying law at the College of William and Mary, and encouraged his colleagues to measure and record weather patterns with him. Thomas Jefferson's passion for meticulous measurement armed him with the ability to validate his theories with strict scientific reasoning.

Jefferson and the Arts

While Jefferson considered himself a scientist first, it was his affinity for the arts that fueled his creative imagination. Jefferson was captivated by music at an early age, so much so that in 1778 he declared music "the passion of my soul"(2). He enjoyed playing the violin while growing up, and often accompanied his sister when she sang (3). Understanding the value of music, Jefferson eventually integrated the arts into the daily regimen and education of his children. Jefferson believed that the arts were an important aspect in the development of the American Republic, primarily because it promoted a sense of freedom and independence in the citizenry. Jefferson's posting as Minister to France in 1785 cultivated his views on the subject, and allowed him to draw a visible connection between the elegance of French artistic expression and the growing uneasiness with aristocracy in France; ultimately leading to revolution in 1789.

Jefferson and Culture

Thomas Jefferson also maintained a profound capacity for cultural understanding. Jefferson was captivated by Greek and Roman culture at an early age (4). He studied Greek and Latin at the age of nine, and took to learning the languages easily (5).

One of Jefferson's most well-known cultural innovations was the Virginia Statute on Religious Freedom, declaring that the government had no right to dictate beliefs to the general populous, particularly in the case of a minority class(6). It was his cultural appreciation for the reasoning of the enlightenment thinkers that led him down this path. In a letter to Peter Carr in 1787, Jefferson wrote, "Your own reason is the only oracle given you by heaven"(7).

At the same time, several dark cultural themes reveal a life that was not free from paradox. Despite evidence that he was against the concept of slavery, Jefferson himself was a slave owner. Scholars have devoted significant research toward understanding the implications of this controversy [a controversy that extends beyond the scope of this work]. Nevertheless, historical evidence supports the claim that Jefferson had an affair with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings, and fathered several children with her.

Jefferson's Secret: Blending Science, the Arts and Culture

As an enlightenment thinker, Jefferson embraced the notion that exploring the nexus between science, the arts, and culture would bring innovative ideas to the New World. Jefferson often blended two or more disciplines into a given innovation, and was constantly mixing and matching various disciplines in order to generate new ideas. At the same time, he viewed freedom as the catalyst for blending science, the arts and culture. Jefferson believed a sense of personal freedom empowered citizens to explore new ideas without fear of persecution or intolerance. Jefferson utilized three of his favorite enlightenment thinkers to shape his views on freedom and innovation. In 1789 Jefferson wrote the following of Bacon, Locke and Newton:

"I consider them the greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and has having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have raised the Physical and Moral sciences, I would wish to form them into a knot on the same canvas"(8).

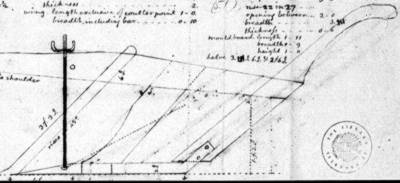

Regardless of the field in which he was working in, Jefferson sought to blend dissimilar areas onto the "same canvas," and applied this approach regularly. His interdisciplinary abilities were particularly noteworthy in the area of Agriculture, a field that Jefferson believed would be foundational to the new American economy(9). Jefferson wrote, "Agriculture is the first in utility, and ought to be first in respect"(10). His scientific abilities, combined with his artistic skill enabled him to design a moldboard plow tailored to the American landscape. His efforts ultimately resulted in the formation of agricultural societies that eventually led to the establishment of the Department of Agriculture.

*Jefferson's Moldboard Plow Design (from Monticello.org)

Jefferson's patented approach is also visible in the Declaration of Independence. Jefferson's use of the term "self-evident" finds its origins in his love for Euclidean Mathematics(11). Euclid's first common notion is that "it is self-evident that things that are equal to the same thing are equal to each other." Jefferson weaved Euclid's definition of the term "self-evident" into the Declaration of Independence. Furthermore, Jefferson's use of the term "equality" can also be traced to his regard for Newton's laws of motion, in which mathematical equivalency governed basic physical principles. Jefferson's application of natural laws in the formulation of an American ethos had a significant impact on the guiding principles of a new American culture. At the same time, his use of the word "happiness" as an inalienable right stemmed from his desire to blend Aristotle's definition of "practical wisdom" into the Declaration(12).

Jefferson's Legacy: A Lesson for Innovators

As a great thinker, Jefferson's passion for blending science, the arts, and cultural understanding was unparalleled -- a mosaic of dissimilar fields that in today's specialized world often remain in their respective corners. Ironically, Jefferson did advocate for specialized study when forming curricula for the University of Virginia in the 1820s. However, it was Jefferson's interdisciplinary approach to problem solving that served as his engine for innovative thinking. It gave him the ability to view problems from a unique lens, and cultivated an innate ability to break new ground by allowing frameworks from a given field to fuel creativity in another.

Leaders in the Information Age should apply the Jeffersonian model of innovation, and cultivate talent by building the capacity for innovative thinking in dissimilar fields. While the proposition of locking scientists and artists into the same room might be considered an uncomfortable undertaking in today's world, the creative investment may result in breakthroughs well beyond the comprehension of a single community.

Ravi Chaudhary is an Air Force Officer and Doctor of Liberal Studies Candidate at Georgetown University. The author wishes to acknowledge the works of Silvio Bedini, R.B. Bernstein, and Merrill Peterson as primary references for this article. Special thanks and acknowledgement to Dr. James Hershman, Georgetown University, for content review.

References

1. Silvio Bedini, "Jefferson and Science," (Thomas Jefferson Foundation, University of North Carolina Press, North Carolina 2002), 29.

2. R.B. Bernstein, "Thomas Jefferson," (Oxford University Press, New York 2003), 359.

3. Ibid., 3.

4. Ibid., 64.

5. Ibid., 3.

6 Ibid., 42.

7. Merrill Peterson, "The Portable Thomas Jefferson," (Penguin Books, New York 1975), 427.

8 Ibid., 435.

9. Bedini, 95.

10. Ibid., 92

11. Bernard Cohen, "Science and the Founding Fathers," (As summarized by Grand Valley Review, Volume 15, Issue One, Grand Valley State University), 102.

12. Richard, McKeon, "Introduction to Aristotle." (McGraw Hill-Random House, New York, 1947), 428.

13. Dr. James Hershman, Georgetown Univ., 2013 discussion.