The recent censorship by the Smithsonian Institution of a controversial video clip by the late gay artist David Wojnarowicz - which contained images of ants crawling on a crucifix - has ignited an uproar in the art world. This incident calls to mind other controversial works of art involving images of the crucified Christ, including Andres Serrano's Piss Christ, Cosimo Cavallaro's My Sweet Lord, and Elisabeth Ohlson Wallin's Ecce Homo.

As an openly-gay ordained minister, theologian, and seminary professor at the Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, I can understand how these works of art might be viewed as being deeply offensive to many Christians. However, I also believe that one of the redeeming functions of these works, theologically speaking, is to remind us of the deeply scandalous and offensive nature of the crucifixion - a perspective that has been all but lost as our culture has become desensitized to the horrors of the cross.

In late November, the Smithsonian Institution ordered the removal of a four-minute video clip from an exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery about same-sex love. The video contained, among other things, images of ants crawling on a crucifix. The video was taken from the film A Fire in My Belly, which was created in 1987 by the late gay artist David Wojnarowicz as a tribute to his fellow artist and lover who had died of HIV/AIDS. The film also expressed Wojnarowicz's anger at his own HIV/AIDS diagnosis, which at that time -- nearly a decade before the availability of life-prolonging antiretroviral cocktail medications -- was tantamount to a death sentence.

In late November, the Smithsonian Institution ordered the removal of a four-minute video clip from an exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery about same-sex love. The video contained, among other things, images of ants crawling on a crucifix. The video was taken from the film A Fire in My Belly, which was created in 1987 by the late gay artist David Wojnarowicz as a tribute to his fellow artist and lover who had died of HIV/AIDS. The film also expressed Wojnarowicz's anger at his own HIV/AIDS diagnosis, which at that time -- nearly a decade before the availability of life-prolonging antiretroviral cocktail medications -- was tantamount to a death sentence.

Over the last month, the art world has been in an uproar over this act of censorship by the Smithsonian Institution. The removal of the Wojnarowicz video occurred after complaints by the Catholic League that the video of the crucifix and ants constituted anti-Christian hate speech. A number of members of Congress had also complained about the clip, which undoubtedly hastened the demise of the video exhibit.

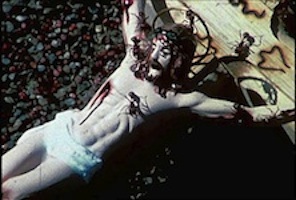

This is not the first time that controversial images of Jesus and the cross have resulted in public outcry and censorship. In 1987, the artist Andres Serrano created a work called Piss Christ, which was a photograph of a crucifix submerged in the artist's own urine. In 1997, the Roman Catholic archbishop of Melbourne unsuccessfully filed suit to prevent the display of the photograph in Australia at the National Gallery of Victoria. Shortly thereafter, several people physically attacked and tried to remove the photograph, which led to the cancellation of the show.

This is not the first time that controversial images of Jesus and the cross have resulted in public outcry and censorship. In 1987, the artist Andres Serrano created a work called Piss Christ, which was a photograph of a crucifix submerged in the artist's own urine. In 1997, the Roman Catholic archbishop of Melbourne unsuccessfully filed suit to prevent the display of the photograph in Australia at the National Gallery of Victoria. Shortly thereafter, several people physically attacked and tried to remove the photograph, which led to the cancellation of the show.

More recently, an exhibit of a six-foot tall chocolate statute of a nude crucified Jesus Christ by Cosimo Cavallaro was cancelled after outcries by the Catholic League (which described it as "one of the worst assaults on Christianity sensibilities ever") and other religious groups. The anatomically-correct exhibit, called My Sweet Lord, was scheduled to be shown in a New York City art gallery during Holy Week of 2007.

More recently, an exhibit of a six-foot tall chocolate statute of a nude crucified Jesus Christ by Cosimo Cavallaro was cancelled after outcries by the Catholic League (which described it as "one of the worst assaults on Christianity sensibilities ever") and other religious groups. The anatomically-correct exhibit, called My Sweet Lord, was scheduled to be shown in a New York City art gallery during Holy Week of 2007.

Even religious allies have paid the price for their support of controversial art. In 1998, the Swedish lesbian photographer Elisabeth Ohlson Wallin exhibited Ecce Homo, which was a series of photographs that depicted Jesus in various lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) contexts. One of the photographs in the exhibit was a modern-day pieta, with a hospital nurse holding in her lap an emaciated and nearly-naked patient who had died of HIV/AIDS. This scene recalls almost perfectly Michelangelo's famous sculpture of a grieving Mary holding Jesus in her lap after his crucifixion.

Despite the public outcry about Ecce Homo, Archbishop Karl Gustav Hammar, who was the primate and head of the Lutheran Church of Sweden at the time, gave his support to the controversial exhibition. Specifically, he allowed the exhibition to be shown in Uppsala Cathedral as part of an annual culture night event. The Vatican was so upset about this support that it cancelled a previously-scheduled ecumenical meeting between Hammar and the Pope.

Despite the public outcry about Ecce Homo, Archbishop Karl Gustav Hammar, who was the primate and head of the Lutheran Church of Sweden at the time, gave his support to the controversial exhibition. Specifically, he allowed the exhibition to be shown in Uppsala Cathedral as part of an annual culture night event. The Vatican was so upset about this support that it cancelled a previously-scheduled ecumenical meeting between Hammar and the Pope.

How should we react, as persons of faith, to these admittedly controversial - and in some cases, offensive - works of art? In my view, one of the redeeming functions of these works, theologically speaking, is to remind us of the deeply scandalous and offensive nature of the crucifixion. As St. Paul writes in his First Letter to the Corinthians, see 1 Cor. 1:23, the cross is a "stumbling block," or skandalon in the Greek, to non-Christians. In other words, who in their right mind would ever believe that the Messiah, the savior of the world, would be tortured, executed, and die a shameful death as a common criminal?

As Christians, we have been desensitized to the horrors of the cross. Instead of understanding the cross as a state-sponsored instrument of execution, the cross has been turned into sentimental jewelry and pious artwork. Instead of seeing the cross as a reminder of God-with-us in the flesh-and-blood sufferings of the world - a theologia crucis - the cross has been turned into a sanitized symbol of victory and ecclesial triumphalism - a theologia gloriae.

God is perfectly capable of redeeming the horrors of cross; that's what the Resurrection and Easter Sunday is all about. Unfortunately, the well-intentioned but misguided belief that we Christians are the exclusive "owners" of the cross - and thus are required to protect it from profanation at all costs - is what often results in incredibly cruel and horrific persecutions such as the Crusades and the Inquisition.

God doesn't need those of us who are Christians to act as intellectual property watchdogs. Rather, God calls us to remember - through the cross - all those in the world who continue to suffer in the flesh and blood, whether through hunger, poverty, disease, sexual violence, hate crimes, or state-sponsored torture and executions.

An earlier version of this essay appeared in 99 Brattle, the blog of the Episcopal Divinity School.