With the story today of Hendrik Coetzee's death by crocodile while attempting to make a first kayak descent down the upper reaches of the White Nile, it brought back memories of my own first descent in Africa with a group of friends, and how lucky we were to have survived.

We were heading out to navigate the Omo River, in southeastern Ethiopia, from its source in the highlands to its mouth at Lake Turkana in Kenya. Nobody had ever run this river before, and as I researched the dangers I was offered many warnings, from tropical diseases to rogue hippos to poisonous snakes to wild cats and violent locals.

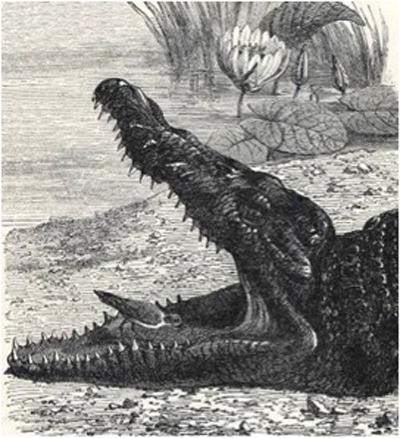

But the one peril repeated over and over, in print and voice, underlined and accented, was the risk of death by crocodile attack. The ancient Greeks called it kroko-drilo, "pebble-worm" -- a scaly thing that shuffled and lurked in low places. The most deadly existing reptile, the man-eating Nile crocodile has always been on the "Man's worst enemies" list. It evolved 170 million years ago from the primordial soup as an efficient killing machine. More people are killed and eaten by crocodiles each year in Africa than by all other animals combined. Their instinct is predation, to kill any meat that floats their way, be it fish, hippo, antelope or human.

To crocs, we were just part of the food chain. Crocodile hunters, upon cutting open stomachs of their prey, often discovered bracelets and bits of jewelry and human remains. Huge, ravening predators, armed with massive, teeth-studded jaws, strong, unrestrainable, indestructible and destructive, crocodiles, if given the chance, eat people. It's their nature. The river is their turf, and we would be trespassing. I found myself in cold sweat nightmares imagining the yellow chisel-sharp teeth of a giant croc ripping my skin apart. This would be the most awful way to die. But I thought about the alternative...law or graduate school leading to a real job... and facing crocodiles seemed the delightful evil of two lessors.

I read as much as I could find about crocodiles before departure, though I quickly discovered not many people had ever navigated whitewater in Africa, and of the few who had, and survived, less than a handful left reliable accounts of their experiences with crocs. I discovered there were two major schools of thought about how to cope while floating a crocodile infested river: 1) Be as noisy as possible when passing through a crocodile pool to scare them off. 2) Be as silent as possible when passing through a croc-infested area so as not to attract attention. The rationale for the latter method was that since crocodiles have fixed-focused eyesight -- meaning they can only see things clearly at one specific distance -- a noiseless boat floating past at the proper distance could probably go unnoticed. One expert at the National Zoo even warned not to laugh in a certain manner, as it resembled the sound of an infant croc in trouble, and the noise would alert all larger crocs with hearing distance to rush to rescue. He demonstrated the laugh, and it sounded eerily like the high-pitched nervous laugh of my partner, John Yost, so I silently vowed to keep topics serious if sharing a raft with John.

Another account was graphically presented in the book, Eyelids of Morning, the mingled destinies of crocodiles and men, by Alistair Graham, and photographed by Peter Beard. It told of a Peace Corps volunteer, Bill Olsen, 25, a recent graduate of Cornell, who decided to take a swim on Ethiopia's Baro River, the next river basin over from the Omo. He swam to a sandbar on the far side of the muddy river, and sat there his feet on a submerged rock. He was leaning into the current to keep his balance, a rippled vee of water trailing behind him, his arms folded across his chest as he was staring ahead lost in thought. A few minutes later his friends saw that Bill had vanished without trace or sound. A few more minutes later a big croc surfaced with a large, white, partially submerged object in its jaws, whose identity was in no doubt. The next morning a hunter on safari, a Colonel Dow, sneaked up on the croc, shot it, and then dragged the carcass to the beach. He cut it open, and inside found Bill Olsen's legs, intact from the knees down, still joined together at the pelvis. His head, crushed into small chunks, was a barely recognizable mass of hair and flesh. A black and white photo of Bill's twisted, bloody legs dumped in a torn cardboard box drilled into my paraconsciousness, and for days I would shut my eyes and shiver at the image.

In the end, I was not comforted by what I learned in my research--if anything, I was a good deal more afraid.

At last we pushed our inflatable rafts into the currents of the Omo River, and swirled into the unknown. It was a stunning passage, and the first part of our exploration went without major incident.

Then about half way down the river, below the Soddu Bridge, the crocodile population increased to frightful numbers, but they generally proved elusive and difficult to photograph. Sometimes we'd catch a blur as one scrambled down a bank, its long jaw slightly agape as it vanished into the water. Usually we spotted them floating in the brown waters, pairs of turreted eyes and long nubened noses, armored backs showing, looking like harmless water-logged pieces of driftwood. Most were leery of our little flotilla, and as soon as they'd sense our presence they would dive underwater, where they could hold breaths for up to an hour. Some bolder ones would resurface for a second glimpse, checking out dinner possibilities, and of course, these gourmands were the biggest, with the beadiest eyes and the yellowest teeth. Their diet consisted mainly of catfish and Nile perch, but they loved the occasional antelope or bird, and a human was special treat. Since most their catches occurred at the eddy line below rapids, they hung out there in big numbers, making the incentive to stay in the raft during a rapid all that much greater. Often when we spilled into the eddy below a rapid a croc or two would charge the boat with motorboat speed. To deter the charging crocs we used the modern method tried and tested by the British Army who made an attempt to run the Blue Nile back in 1968: we shouted obscenities and threw rocks at the approaching heads.

On day 15 we were feeling pretty seasoned, accustomed to sharing the river with the crocodiles. There was a subtlety in the predators that defied description and eluded cameras, a capacity to move without exciting attention, a wraithlike quality of unobtrusiveness. Most crocs dove as soon as we'd make a peep, and as we wanted to get some photo documentation of the crocs, we decided to withhold shouts and croc rocks until the last second so we could get some movie footage.

George was our cinematographer with his video camera, and he was grinding happily away as a 15-foot croc slipped off the bank, and started steaming towards George's hippo-gray raft. Water skimmed off his snout like spray off the bow of a speedboat. George desperately tried to focus. Twenty feet. George steadied himself in the raft, tightened the grip on his camera. Ten feet. George could see the beady eyes and the acid-yellow teeth. Five feet.

George saw the fleshy yellow lining of a crocodile's throat filling the entire viewfinder. WHAM! George came back to reality to find the 36 sharp teeth on each jaw wrapping around the deflating tube of his boat. Cursing, George jumped to the oars and started rowing downstream fast he could to prevent a half-ton of carnivorous vengeance from climbing on board.

My friend Lew Greenwald and I were upstream, and turned when we heard George shouting. I started rowing as hard I could to catch up, but George was practically hydroplaning, dragging the leviathan like a water-skier, and I couldn't make any headway. Over my shoulder I watched as Diane Fuller, George's wife, leapt to the bow of the boat and started beating the bewildered croc on the head with a metal bailing bucket. Crocodiles have unidirectional jaws; they can slam their jaws shut like an iron trap, but almost any pressure can prevent their opening them. The croc's teeth were stuck in the fabric of the boat, so it couldn't release, and it began shaking the raft back and forth like a dog with a rag. George rowed faster, and even though he was dragging several hundred pounds of crocodile, I believe he set a new world-rowing-speed record, and left me in his wake. After a seeming eternity, perhaps ten long minutes, the Nile dragon finally broke free and disappeared into the river's depths, still hungry, and shedding perhaps crocodile tears. The front section of George's boat was reduced to a shriveled blob. When Lew and I caught up, George was still cursing. Not because of the close call, or the punctured raft. George was livid because he missed the shot.