This is the second installment in a two-part series. Read part one here.

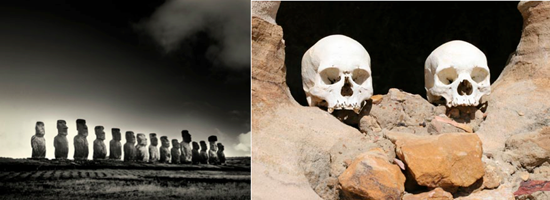

I continue up the barren coast a short distance, and stop at a bluff to watch the sea fling veils of water a hundred feet into the air. At this meeting of rock, sea and sky -- mass, energy, and light -- I am sufficiently sated to turn inland, and stitch towards higher ground. My horse, inaptly named Pegasus, brings me to the base of Ahu Tepeu, a magnificent beetle-browed statue crowned with a red stone headdress weighing eleven tons. The achievement of donning this fellow's hat must be compared with putting a man on the moon today. The best of origin theories notwithstanding, the erectors likely had little wood at their disposal, and limited manpower; but the statue stands, proud in his haberdashery, lips peculiarly pursed, eyes blind, mouth in solemn silence, yet somehow alive in the deadness of stone.

Ahu Tepeu faces inland, as do almost all the statues. A popular theory is that the statues were created to represent important people who had died. The power of the deceased was thought to be transmitted to descendants through the eyes of moai. Thus, all the statues originally faced the center of the island, toward villages. As I guide Pegasus behind the statue while gaping at the huge hat, he suddenly rears and whinnies, almost tossing me to the dirt. Looking up, I see the source of his fright -- from this vantage it appears the statue is toppling over towards us, an illusion that matches the spooky nature of the place.

For the next few hours the ride yields nothing, save stark vistas, a rough pitch-stone terrain, and wild horses. The island is entirely volcanic, with three major cones forming the points of a triangle. As I zigzagg northwards I find myself ascending the talus slopes of the island's highest peak, the extinct Volcan Aroi, 1400 feet above the sea. Halfway up an incongruous grove of banana trees circumscribes a rock outcropping. I dismount to investigate.

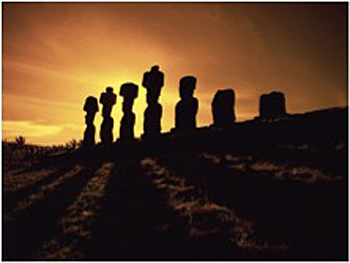

There is a cave beneath the wide leaves. I poke my head inside, and wait for eyes to adjust. There appears to be a skull with horns, perhaps of a ram, not far within.

A boulder blocks the entrance, but with my back into it I am able to roll it aside. A shaft of light strikes the horned skull, and sends a shiver through me.

I lower myself into the grotto feet first, kicking aside a latticework of spider webs. Inside, I squirm to my knees, and crawl through the damp, black velvet of darkness to the skull, which is lit by a pinpoint of sunlight. Next to it, in the half light, I can make our two more skulls. I reach to pull one closer, then coil back like a snake-bitten dog.

They are two human skulls. I bring them to the surface to photograph, and see that each has a pen-sized holed in one side of the head, and a jagged, gaping grapefruit-sized hole on the other. Forensics is hardly my forte, but the marks look like bullet holes to me. What chilling stories would these heads tell if they could speak? Murder? Accident? Cannibalism? Double suicide? How old were they? One year, one hundred? Did they know the riddles of the islands?

Later, back in Hanga Roa, I speak with Claudio Cristino, an archeologist from the University of Chile, who spent years studying and mapping the island's thousands of archeological sites.

"Those caves are sepulchers, burial chambers for the victims of smallpox back in the mid-1800s," he tells me.

Claudio agrees with Professors Flenley and King that Easter Island at its height supported 15,000 people, a bustling South Pacific station. When Captain Cook arrived he found only 600 men and fewer than 30 women eking out existences on an island with only stunted mulberries and tiny mimosas for trees. "On the entire surface of the island, there is not a tree that merits being called that," wrote naturalist George Forster, who accompanied Captain Cook. If the ecological devastation theory holds, most of the population loss was the result of forest obliteration more than 600 years before Cooks' landing. But things got worse. In the early 19th century Peruvian expeditioneers, looking for cheap labor, abducted Easter Islanders as slaves, and introduced smallpox (which had been earlier gifted to South America by the Spanish Conquistadors), consumption, and venereal diseases to those remaining. By the mid-19th century the island's population was decimated. At its ebb, in the 1870s, there were just 111 inhabitants. Today the population is around 5,000, and the place still seems underpopulated.

After my skullduggery at the cave I spur Pegasus onward and upwards. I come to a simple farmhouse, an island of life on the desolate volcanic slope, where a dark, disheveled figure steps out to meet me. As he steps from the shadow of the mountain I can see that that left side of the farmer's face is contorted in bizarre lines, with lip and eye drooping like melted butter. He is a leper, one of about 30 on Easter Island, and his disease had paralyzed and disfigured his face. Now he lives in isolation on the world's most isolated isle.

When Chilean navigator Captain Policarpo Toro negotiated to transfer Easter Island to Chilean sovereignty in 1888, he brought with him several islanders who had been living in Tahiti. Missionary records indicate that one passenger was visibly ill with leprosy, already showing some limb paralysis. He was the first.

The disease spread quickly, and a decade later a leper colony was built not far from this farmhouse to isolate the sufferers. By the 1940s, forty islanders had the disease. Then, with the island-wide vaccinations in the 60s and 70s, the disease was at last officially eradicated. Now the last of the lepers have staked out homesteads in the far corners of the islands, such as the one here on the side of the volcano.

We nod and try to exchange salutations, but are hampered by the impenetrability of a native dialect I don't understand. He smiles, and waves me towards his home, so I slip off Pegasus and follow him inside. There he pulls a black pot off the stove, and serves up a cup of steaming, delicious real bean coffee. It is an unexpected treat, and when I ask in my best sign-language what I might give him in return, he shakes his head. I insist, and finally, after some thought, I pull off my Hanes T-shirt and hand it to my host.

After bidding goodbye I continue the ride up the fallow grade, reaching the summit mid-afternoon. A shallow crater, lush with rain-nourished grass (the island is devoid of running water) forms an imperfect crown. Some of this grass is papyrus, known as totora, like that found along the shores of Lake Titicaca, and the stuff Thor Heyerdahl believed made up ancient ocean crafts.

Pegasus picks up speed and fire descending the eastern scree slope. After an hour's hard ride I crest an empty ridge and look down upon Easter Island's most resplendent sight -- Ahu Akivi, or "The Seven Monkeys," as the islanders have nicknamed them. Since restoration by Chilean archeologist Dr. Gonzalo Figueroa and Professor William Mulloy, former head of the Department of Archeology at the University of Wyoming, the seven monkeys have become the most renowned and most photographed residents of the island. They stand not like apes, but rather soldiers guarding a wasteland, fixed in scorn, forever watching a vacant landscape and the watery azimuth beyond. Their graven images serve as tongue-tied testimony to a past about we can only surmise and quarrel.

Minutes later my once-glue-factory-candidate is galloping back Preakness-style, a cat that looks like me clinging to its back. Minus my right stirrup I screech into Hanga Roa, pull into the first tavern, wrap the reins around a hitching post, and mosey inside for a brew. I order a Brazilian import called Xingu, and walk outside to pull the fleece saddle off Pegasus's sweaty back. A gust of wind spins down the lane and pitches dust into my eyes. A chill runs through me. I still have no shirt, having left mine with the leper on the hill, but this breeze seems ghost-like, something from sculptors past perhaps, makers of great art, but failed stewards of land, resources and culture. Are we any better? Is there a message in the stony stares of the island sentries?

I take a long draw from my Xingu, drink in the glazed Pacific horizon, and the splendidly lonely landscapes of the island. I can hear the sea murmuring something, but it is indecipherable to me. The sun is setting, but I imagine I see a slight, sly smile on the lips of the statue on the ridge.