Matthew Fisher was Born in Boston, grew up in Three Rivers, Michigan, and lives and works in Brooklyn, New York. He received a BFA from Columbus College of Art and Design, and an MFA from VCU. He was a recipient of the NYFA Fellowship, and a resident at Yaddo, the Millay Colony, and the Vermont Studio Center. He recently had a solo show at Mulherin+Pollard Projects, NY, and his current show at Ampersand Gallery, Portland, Oregon will run through March 23rd.

Please visit Ampersand Gallery for more info on his current show.

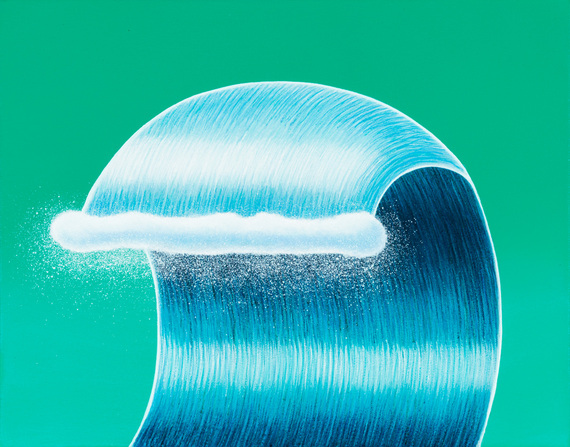

Wave (for J.D.), 2014, Acrylic on canvas, 15 x 19 in, courtesy of the artist and Ampersand Gallery, Portland, OR

RH: You seem to always play with the idea of genre. You've dealt with history painting, portraiture, still life, and landscape -- but your involvement is fresh, and very much your own.

MF: Painting things has always been a part of my thought process. It seemed like every young painter in school wants to have the brash of Robert Motherwell or the skills to paint like a photograph. I quickly learned I was neither. I found myself fussing over a brushstroke I had just made, trying to improve it. To start a painting, there had to be something, a representation, for me. I love abstraction -- I just can't paint like that. I love the idea of an image being nothing and everything at the same time, but I just don't think that way. While these new works come closer to abstraction than I have previously ventured, they remain grounded in our world. Our knowledge of what nature is, helps us complete the images.

RH: Landscape was always a major character in your work, even as a setting, and now it is the focal point. How did that shift come about?

MF: After my first solo show at RARE in 2009, I wanted to try to make paintings without using figures. For the next two years I made symbolic still life paintings that hinted at a presence without actually showing a figure. After my second show, I hit a wall. I saw my process of painting as piling objects and animals together, creating a forced narrative out of associations of proximity, and that was it. After months of trying to paint something, I walked into the studio and told myself to make a drawing of nothing. Nothing is never just nothing; but, I saw the horizon line, where water meets sky, as being both empty and full. The openness of looking out over an endless sea was the nothing I was looking for.

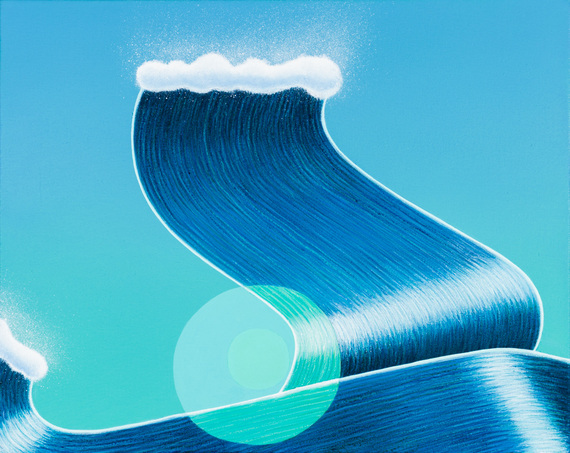

Dead Can Dance, 2014, Acrylic on canvas, 16 x 20 in, courtesy of the artist and Ampersand Gallery, Portland, OR

RH: The waves in the newest paintings feel alive, yet they are composed primarily of geometric shapes. There is a tension in their simplicity. You can feel this very strict containment of the water, which gives them a power. At the same time, they are painted in softer, pretty colors that make them playful and Pop.

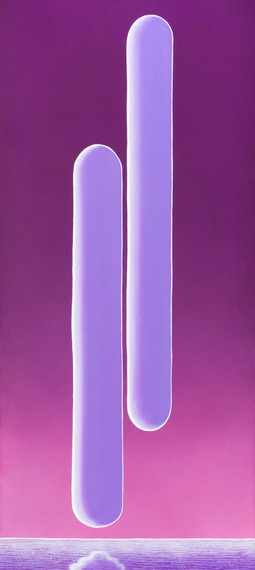

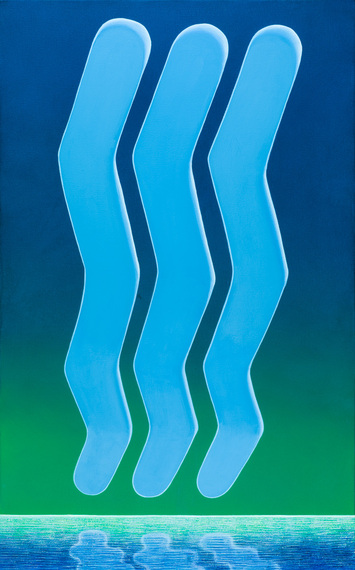

MF: The new work exists in an interesting limbo between natural and artificial, of showing action and stillness, depicting an image that is universal, but also personal. Being both, while simultaneously being neither, gives the generic images I use (a wave, cloud or sunset), a new edge. The colors come out my use of acrylic paint. Their saturated colors help complicate one's expectation of what is natural and real. The same goes for the use of geometric shapes. How else are you going to paint these images?

RH: They also play with the formal language of painting. There is a wonderful sense of design. Do you focus primarily on those aspects of an image or is there a narrative involved as well?

MF: The beauty of painting is that there is this formal language, a deep history of what has been done. The materials haven't changed, it's always been pigment rubbed onto cloth that is stretched over wooden sticks. By continuing to work within the material limitations, I am more able to play with the elements of design, color and image. I first got into art through photography, and the act of looking through a SLR camera lens trained my eye and brain to think inside rectangular shapes. Jack Beal taught me to respect the edges of compositions by allowing objects or actions to go right up to the edges, but never over them. Often objects only leave the bottom edge of my paintings. Lately, I have found my best ideas come to me when I have no ideas. I force myself to play with and push out what ever comes to my mind in that moment of clarity. This creates the most interesting images for me. Another strategy is to do the opposite of whatever I was doing before. By challenging my color or composition choices, I better understand how they work by seeing them in a new way.

Royal Onement, 2014, Acrylic on canvas, 40 x 18 in, courtesy of the artist and Ampersand Gallery, Portland, OR

RH: Your work balances highly rendered areas, highly un-rendered areas, and painterly effects. Do you see this as giving the paintings a type of tension?

MF: My painting process has always started from the furthest point back. By painting the sky first, I can use the larger brushes and many layers of transparency to create atmosphere and gradations that cannot be made with my smaller brushes. Still, before I begin working on the foreground, the background has to contain something that excites me. This can result in up to ten layers or more of paint to create a color fade before I begin to add the rest of the painting. Despite the clean edges in the final painting, my painting process is very messy.

RH: Funny to see the sparkle foam as painterly magic.

MF: The sparkle and spray is, in fact, a mini splatter. The force and energy of the crashing wave is perfectly frozen by this painterly action. The spray looks real, because it is real. Still, it doubles as a stand in for what real spray looks like. Again, I am playing with this notion of being both real and fake, of stillness and motion. For me, the beauty of painting is that it can be so simple that it becomes deep.

RH: There are nods to numerous painters (Lissitzky, Arp, Léger, and countless Americans). Are these references at the forefront of your thoughts or a more integrated part of your process?

MF: Art History is always on my mind. About three or fours years ago, I stopped looking at as much art as I had been previously. This choice was not out of ignorance, but rather an attempt to keep my mind clear. After years of working in galleries, framers, and art moving companies in New York, I have constantly been exposed to all kinds and periods of art. I am not completely interested in referencing other painters' work, of making art about art. That type of inside joke bores me. I want to be able to take and use whatever I wish, in order to make the painting work. This kind of arrogance requires a knowledge and understanding of art. After two decades of looking and studying art, I feel comfortable to pull away, or at least walk on the other side of the street, when I make my art. The images I make aren't completely new; no artist today could hold themselves up to that standard. Rather, my paintings play with my own visual assumptions of reality, history, and knowledge. What you know isn't always what you see. And what you see isn't always what you know.

Green the Night Turned, 2014, Acrylic on canvas, 40 x 25 in, courtesy of the artist and Ampersand Gallery, Portland, OR

RH: Your work has always merged a kind of realism, with Pop cartoonishness. I know you like a lot of the Chicago imagists. Did they influence your thinking early on?

MF: Roger Brown was my idol in art school, and still is. His language of representation and abstraction, of playing with space and scale is so good. He also opened my eyes to other ways of making and showing space within a painting. Why must American art obey western perspective or photographic space? If Giorgio de Chirico tore up the perspective handbook, Roger Brown put it back together, but in a different order. The Chicago Imagists also looked toward the untrained artists to help them understand what it means to make an image. Attending art school in Columbus, Ohio, I was exposed at an early age to two of America's greatest 20th century folk artists: William Hawkins and Elijah Pierce. Their freshness and strangeness was the answer to so many art school questions posed to me. Like Roger Brown and Ray Yoshida, Hawkins and Pierce taught me the importance of imagery, narrative, and gave me permission to play with depicted space.

RH: I think you introduced me to Rockwell Kent in about 2002. These new paintings seem to have a lot of Kent in them. Is he still on your radar?

MF: Rockwell Kent is one of American's great painters. Kent's paintings contain an energy and sensibility that only come through observation. Although he's not the influence on me that he was before, his truthfulness in details give his work the reality that my work plays against. As specific as his work is, in terms of actual location, mine is universal. The Vulcan proverb "Only Nixon could go to China" is never far from my mind. I can only make these paintings because I live right now.

Half Moon Bay, 2013, Acrylic on canvas, 14.5 x 12 in, courtesy of the artist and Ampersand Gallery, Portland, OR

RH: Thinking back, though your work can have a kind of sadness or even dark psychology, the paintings always feel celebratory in a way. There is a joy in the 'event' of your paintings, even in their restraint. Do you see the work as emotional or joyous?

MF: That's an interesting question. When asked if the works are depictions of sunrises or sunsets, I have to answer that I have seen more sunsets than sunrises in my life. There is a practical side to these images, a bewilderment of nature. Waves have been crashing and clouds floating for as long as time itself. Nature always does its thing; we're just in the way. The fun thought is that there is a world of life hidden just below the surface. These exact truths don't fuel my work, but I just love the idea that a single line, horizontal to the bottom of canvas, automatically sets up a here and there, us and them, land and sea, lost and found. It's as old as time.