Do homeowners who are underwater on their mortgages deserve to lose their homes? That's what finance commentator Barry Ritholtz says, in a post called "More Foreclosures, Please." Ritholtz must have been channeling his inner Rick Santelli when he wrote that "the boom and bust saw irresponsible and reckless behavior by lenders and home buyers alike," adding that mortgage relief programs for homeowners reward those who were "reckless, speculative, and foolish" while punishing those who are not.

It's not reasonable to put Barry Ritholtz in the same category as Santelli, of course. Ritholtz is a highly informative, widely quoted writer on economic issues. Santelli's the frat-boy trader turned CNBC host whose rant about "rewarding the losers" got a cheer out of some morons on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (and started the Tea Party movement). But Ritholtz puts financially beleaguered homeowners in the same "moral hazard" dumping ground as the banks who wrote their mortgages, suggesting that both of them "overused leverage, disregarded risk, (and) ignored history." Is that really fair?

After all, what kind of information was available to the average home buyer during the last decade? How would the average reasonable person have decided whether to buy a home or what kind of mortgage to use -- in, say, 2004?

They probably read articles like the one published in February of 2004 in USA Today ("America's newspaper") with the headline "Greenspan says ARMs might be better deal." "Overall, the household sector seems to be in good shape," said Greenspan, who added that adjustable-rate mortgages might be the right choice for many homeowners. Greenspan enthusiastically promoted the new-style mortgages that later played a big role in the meltdown: "American consumers might benefit if lenders provided greater mortgage product alternatives to the traditional fixed-rate mortgage," he said.

Greenspan wasn't just Chairman of the Federal Reserve at the time. He was the man the press kept touting as a genius, the one they called "Maestro." Were homeowners guilty of a "moral hazard" for listening to him? Should they face foreclosure because they weren't reading Nouriel Roubini or Paul Krugman or Joseph Stieglitz?

Ignorance of the law is no defense, but ignorance of contrarian economic thought circa 2005 should be. If Greenspan and Geithner and Paulson and all the talking heads on CNBC and the other networks couldn't see the bubble, how could the average home buyer?

The truth is, most people buy homes because they need a place to live -- and because for generations they've been told that buying a home is preferable to renting. Our tax code is structured to encourage home ownership, and the ownership message is reinforced in everything from news reporting to popular culture. (Think Miracle on 34th Street.)

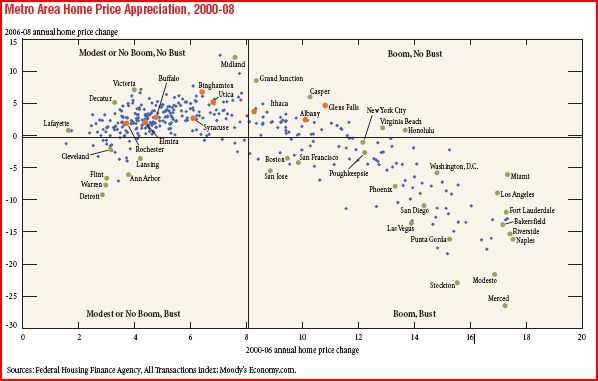

And generalizations about irresponsible, speculative borrowing overlook the fact that the nation's housing problems vary widely by geography. Some areas aren't having a housing bust:

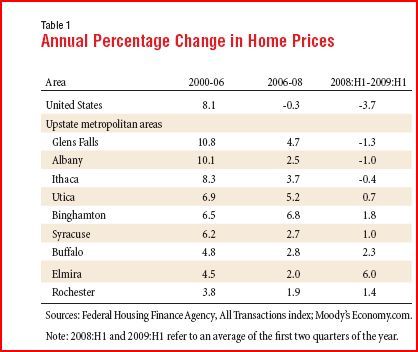

Is a homeowner in Glens Falls, NY any more "reckless, speculative, and foolish" than one a couple of hours down the road in Poughkeepsie? Poughkeepsie experienced a boom in prices followed by a bust, while high-performing Glens Falls experienced a boom with no bust. West of Glens Falls, my home town of Utica did pretty well too, as this chart illustrates:

It probably helps that Utica experienced its financial collapse a long time ago, so housing prices were already unusually low.

Here's something interesting: The areas with stable housing prices had a much lower percentage of nonprime loans than the country as a whole. As the report's authors mention, the explanation for that probably "runs in both directions--an increase in nonprime lending led to more significant home price appreciation, and more rapid home price appreciation led to a rise in nonprime lending."

In other words, it was a cycle: Risky loans drove housing prices up, and climbing housing prices led to greater availability (and selling) of risky loans. That's not a borrower problem -- it's a pattern of lender behavior. It's a sign of banks driving a speculative frenzy as a "get rich quick" scheme, then leaving the borrowers with the wreckage.

Ritholtz makes some excellent points about the weakness of HAMP (the Home Affordable Modification Program), and its tendency to reward banks for their very real "moral hazard." The biggest problem with the revised HAMP program isn't that it's too generous to troubled homeowners. It's that it's a "pretty please" program that only requires lenders to consider lowering the principal on home loans (or, in the Orwellian language of the program's Fact Sheet, "servicers will be required to consider an alternative Modification approach" - "required to consider" being one of those self-contradicting phrases George Carlin used to rattle off, like "jumbo shrimp.")

But the idea of principal reduction -- whether it comes from HAMP or individual lenders like Bank of America -- is a reasonable one. Most reductions in principal will still leave homeowners owing more than their house is worth, which should give them their just portion of punishment for any "moral hazard."

"More foreclosures, please" is exactly what we don't want. Ritholtz is understandably concerned about the unfairness of "rewarding" homeowners who got in trouble in a way that keeps prices higher for those who behaved responsibly. But he paints an overly rosy scenario of bad actors being driven from their homes like poltergeists, so that new and vibrant families can move in -- families that can afford the mortgage and have money left over to spend in the local economy. The real solution is going to look less like a ghost story and more like Tim Burton's Beetlejuice, where the ghosts and the living learn to live together happily.

The millions of homeowners who got in over their heads have already suffered a lot. Let's get them some help. And let's keep the focus on the people who caused this problem: The bankers who got rich off these schemes, and the politicians and regulators who let them do it.

___________________

Richard (RJ) Eskow, a consultant and writer, is a Senior Fellow with the Campaign for America's Future. This post was produced as part of the Curbing Wall Street project. Richard blogs at:

Website: Eskow and Associates