I co-authored this piece with Stephen Beban, a research intern working at FairVote this summer.

FairVote appreciates the data-driven journalism of Nate Silver's FiveThirtyEight. We read with interest Eitan Hersh's June 21st article, "With Trump in the Race, The Battleground Is Everywhere," outlining Hersh and Bernard Fraga's analysis on competition in US elections. Our own research reveals troubling trends about the scope of meaningfully contested elections, but Hersh and Fraga dispute our concerns. FairVote intern Stephen Beban and executive director Rob Richie have written two posts in response. The first one focuses on presidential elections; the second post will focus on Congress.

Professors Hersh and Fraga's analysis of electoral competition makes the case that "the picture is much rosier" than FairVote characterizes in calling one of our reports "dubious democracy." But we stand firmly by our position. This month we will release the latest edition of our Monopoly Politics report on congressional elections, and will follow up to this post with a preview of its findings. In this first post we examine the presidential elections and show that that levels of electoral competition in states are far from healthy. Without rose-tinted glasses, this conclusion is inescapable.

Accurately Measuring Competition

In looking at elections for president, governor, U.S. Senate, U.S. House and state legislature over the 2006-2012 period, Hersh and Fraga judge there to be "robust competition" based on two facts: that "the typical voter in this period saw a competitive race for one in four contests for which he/she could vote," and that, as a result, "about 90 percent of Americans saw at least one close election between a Democrat and a Republican." However, this is not nearly as positive as it sounds, when put in context.

Let's first consider Hersh and Fraga's generous measure of "competition," which they define as races won by less than ten percentage points. Looking at the national popular vote, every presidential election since 1984 has been competitive by that definition, erroneously including George Bush's comfortable win over Michael Dukakis in 1988 and Bill Clinton's re-election against Bob Dole in 1996.

But of course presidential elections are contested state by state, with important implications for the number of voters that experience a competitive election even in a close Presidential race. We can further demonstrate that the measure of competitive is too broad by highlighting several states won by less than 10 percentage points that were not treated by either campaign or the media as competitive. To make our point, we'll focus on results from 2000 to 2012.

During this period, 19 of 50 states were won by the same party in all four of these elections by margins of at least 10 points. The fact that the remaining 31 states were all won by less than 10 percentage points at least once might seem to confirm the conclusion that many voters experience a "competitive election" over time, but that conclusion is easily rebutted by looking at a few examples from those 4 elections:

- Democrats won California, Delaware, and New Jersey by an average of more than 15%. In 2004, however, John Kerry won these three states by less than 10%: California by 9.9%, Delaware by 7.6% and New Jersey by 6.7%; yet none were considered battlegrounds that year - indeed, out of nearly 250,000 presidential TV ads in the peak season of the campaign, not a single one aired in any of those states.

- Georgia, North Dakota, South Carolina, and South Dakota were all won all by Republicans by an average margin of more than 10%, but in 2008, McCain won them by less than 10%. Once again, neither campaign treated them as battlegrounds, so those states' voters did not experience a "competitive" election.

Underscoring this point, FairVote has created what it calls the Presidential "Attention Index," which looks at the share of campaign events and television ads a state received in the post-convention period. A score of 1.0 would mean a state received attention in proportion to its population size. In 2012, 37 states had an Index of less than 0.01, which means they received less than one percent of the attention we would expect it to receive based on state population alone. Of those 37, 34 were also comparably ignored in both 2004 and 2008 and are not considered potential battlegrounds in 2016-- in other words, a large majority of states are recognized as fundamentally uncompetitive. And even competitive states are not created equal. Those closer to being the tipping point state in the battle for 270 Electoral Votes receive disproportionate attention from the campaigns.

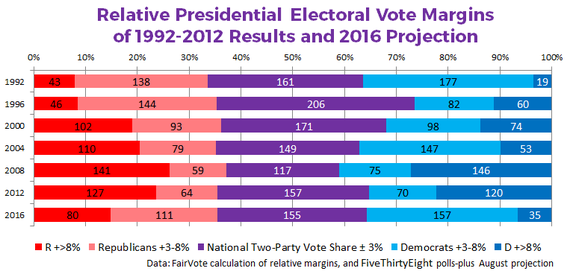

Adopting a more reasonable definition of competitiveness (one more in line with the perceptions of candidates, voters, and forecasters), presents a far more limited scope of competition. Over the last six elections, the outcome in a clear majority of the Electoral College has been predictable- after all, winning a state 51-49% has the same consequence as winning 99-1%. Consistently, only about a third of the map in each election has been truly in doubt, with the rest of the country playing spectator.

Variation Over Time (or Lack Thereof)

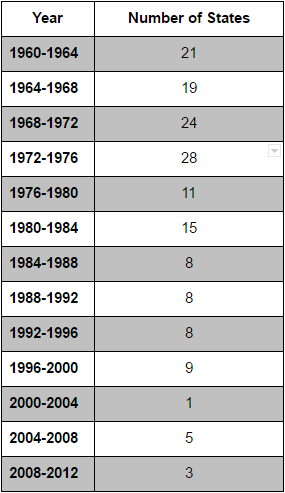

Perhaps Hersh and Fraga's argument might still be somewhat justified if enough states that made up the list of battlegrounds changed cycle-to-cycle - so that voters would have an opportunity for their state to be contested and gain the attention of the candidates over time. But this is not the case; in fact, it's remarkable how static our elections have become. In a 2013 Presidential Studies Quarterly article by FairVote staff, we explain in detail how most states are becoming less competitive and how little states now tend to change in partisanship elections. Consider this excerpt and an associated table:

In 2012, just three states shifted their partisanship by more than 3.9%, all of which were small and ignored by the campaigns: Alaska, which became more Democratic without its governor on the Republican ticket; Utah, with a strong Republicans shift influenced by Mitt Romney being a Mormon who had coordinated the state's 2002 Winter Olympics; and West Virginia. Only five states in 2008 had outcomes that deviated at least 3% from their 2004 partisanship: two states moved sharply towards Democrats (Hawaii, where Barack Obama grew up, and Indiana, where Obama benefited from his 2004 Senate campaign in neighboring Illinois and from building a campaign operation in a fiercely contested presidential primary) and three Southern states that moved sharply toward Republicans (Louisiana, Tennessee and Arkansas).

Table: Number of States Shifting Partisanship 5% or more in Consecutive Elections

2016: A Continuation of the Trends

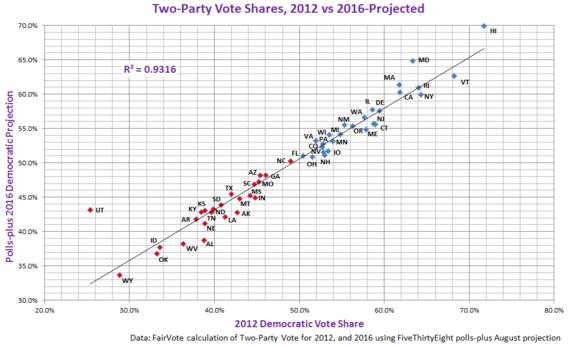

2016 gives no indication of reversing these trends. FiveThirtyEight's polls-plus model consistently shows that two-thirds of voters live in states that are likely to be uncompetitive in November, similar to historical results, with a clear minority whose votes will be decisive (even if, as in Florida 2000, they may not be representative of the overall result). So the playing field still features few competitive states.

And the cast remains fairly static, as demonstrated by the strong correlation between the 2012 results and 2016 polling (as others, such as Alan Abramowitz, have pointed out too). A good illustration of this is the similar cast of states that FiveThirtyEight has identified as likely tipping points in 2016: Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Michigan Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Wisconsin. If these states sound familiar, note that they are the same states that were closest to the national median in 2012 and 2008, with the exception of Indiana in 2008. They are the only states where the major party tickets held campaign rallies after Labor Day in 2012, and this year have been the subject of more than 80% of the campaign rallies to date by the major party candidates since the California primary on June 7th.

Despite the drama of the 2016 campaign and Donald Trump's allegedly volatile impact, the battleground is emphatically not everywhere - and the states that matter are overwhelmingly familiar and predictable.

Finally, we want to emphasize that it truly does matter that some states count and others don't to the campaigns. Don't expect candidates to waste a second's thought or a dime of spending trying to influence the views of more than half the nation that lives in the uncompetitive spectator states - and, as a result, voters in these states will turn out to vote at lower rates. And it's not just what happens in elections. A growing body of scholarly analysis - most notably, John Hudak's Presidential Pork - shows that swing states are showered with more federal dollars that are directed by the executive branch.

In Part Two, we'll turn to House races, and two statutory changes that would allow us to remove the well-deserved adjective "dubious" from our state of democracy.