"Do you know my grandson: Doctor Accordino?" That was my grandmother's go-to question to any apparent medical professional who entered her hospital room -- doctors, nurses, chaplains, social workers, janitors. When someone acknowledged they knew me -- perhaps a doctor who had taught me in medical school, perhaps someone who was merely being polite -- my grandmother beamed.

To many she was "Mildred Kadish." To me she was "Gram." And when she fell in the dining room of her assisted living facility (the result of her commitment to high heels long after her peers had acquiesced to walkers), she became, in an indirect sense, my first patient. My family and I found ourselves her hospital advocates, and I, as the only doctor in the family, became her chief overseer. She happened to be hospitalized at the medical center from which I received my medical degree, and even when she was most confused -- clinically delirious -- she knew I had just graduated from medical school and remembered to ask all who entered her room if they knew me.

Gram was an extraordinary person who happened to be hospitalized for a fractured hip, not the other way around. As a doctor-in-training in the hospital with her, I experienced firsthand a powerful conflict between medical staff and patients and their families. Specifically, the emotionally intense demands of dealing with acutely ill people can drive medical personnel to objectify a patient at the moments when a patient and her family most vulnerably yearn for personalization and humanity.

That hospitalized people are vulnerable is a trope of modern medical care, and it was an unavoidable truth as my family and I shepherded Gram through the medical system. There are the stories of patients who die because of a misdiagnosis by doctors do not ask the right questions. Those are the stories that at their worst ascend into the queue of media coverage. But for each of those stories, there are thousands of quotidian moments that similarly complicate medical care. Once, for example, a nurse gave Gram a sleep-inducing narcotic because Gram had nodded when asked whether she was in pain. In fact, Gram had been feeling fine and hadn't understood the question. Her hearing aid had been turned off. Gram was at one of the country's major medical centers, home to the best resources and finest practitioners in the world. I am deeply grateful for the training I received as a student there and the treatment my grandmother received. But even on Mount Olympus of medical care, every day we encountered flaws in Gram's treatment and were constantly reminded how important it was to advocate for her.

If the immediately preceding sentence was our most important lesson, one of our applied learnings was that there were many ways we could partner with her medical team. Consider a simple example: Acknowledging that her delirium was a waxing and waning clinical condition that occurs in as many as 50 percent of hospitalized elderly patients and is usually worst at night. Solutions devised: We got her a bed by a window so that she would know the time of day. Nurses visited frequently to orient her. Her medical team also minimized the number of tether lines -- intravenous and foley catheters -- restraints which can trigger frightening delusions when a person loses their locational bearings in the middle of the night in a hospital. And we decorated her room. We filled it with familiar books, mementos, and photographs of her life ("These tchotchkes! Why so many tchotchkes," she would mutter). These jogged her memory, anchoring her mind when she woke every four hours in an unfamiliar room, stirred by a nurse who had come to take her vital signs. Another thing these tchotchkes did, we hoped, was humanize her to those caring for her. At her bedside, we took every opportunity to tell her care providers a quick vignette about Gram's amazing life and strong will. We knew her medical team would never feel our depth of affection, but we hoped that by conveying some piece of her, we would impact her care. To know her was to love her.

Gram's will and comic timing never waned. Complications were inevitable for someone her age, which at Gram's request I'm not at liberty to disclose. The complications extended her hospital stay from days to weeks. But she was always "wonderful!" even when she wasn't. We called that spirit her show-must-go-on attitude. It descended from her performing arts background. In the 1920s and 1930s she was a well-known Vaudeville actress, performing under the name Mildred Roselle. At 6 years old she sang to departing World War I troops. She appeared on the cover of sheet music of songs she popularized like Spencer Williams' 1929 hit "Susianna." In her 20s she headlined and recorded albums with big bands such as Ben Pollack, performed on Broadway, and toured the country. Later she did significant philanthropic work with The Troupers, a group of Vaudeville alumni, all women, who raised money to fund scholarships for undergraduate performing artists at Juilliard, Columbia, and NYU. But she always said her greatest casting -- a role for which she won 30 consecutive Tonys plus a number of Oscars, Grammys, and Emmys -- was as a grandmother. She took her grandchildren around the world, hot air ballooning in Kenya, white water rafting in Alaska. "Life's a banquet, and most poor sons of bitches are starving to death," she would say, acknowledging that line was made famous by Auntie Mame but claiming that she had come up with it first.

When I started my residency, I would typically spend 12 hours in the hospital with my patients and then head over to see Gram. As I made the daily transition from resident physician to family member of a hospitalized patient, I reflected on how family, albeit always with good intentions, would sometimes inadvertently obstruct care. For example, I had one patient who was undergoing treatment for leukemia. I was often paged to the patient's bedside early in the morning where his sister was yelling at nurses, whom she assumed were making mistakes. My attending and I and the rest of the oncological team organized family meetings to discuss her concerns. She began to trust us. Over the course of several chemotherapy admissions, we built a therapeutic alliance, to borrow a term from psychiatric practice. While the concept of doctor-patient alliance seems self-evident, it has not historically been central to medical education. Only recently has that been changing. Physicians like Dr. David Hirsh at Harvard Medical School have developed "continuity" curricula, which are re-shaping clinical education. Dr. Hirsch has demonstrated that by having medical students follow cohorts of patients through both times of wellness and illness, young doctors develop a broader understanding of a patient within a family and society rather than solely in the context of an acute disease, which is traditionally the focal point of medical education. In turn that broader human understanding leads to more effective communication and better care.

After several weeks in the hospital, Gram was discharged to a sub-acute rehabilitation facility. Her recovery was slow to the point that it was not clear she was actually recovering. She was frustrated about being confined to a wheelchair, no longer able to wear heels, but still her theatrical spirit loomed large. In March 2012, I gathered some friends to celebrate Gram's birthday. We staged a sing-along at her nursing home. Gram led a round of "Broadway Baby." It was her last birthday. She said it was her best.

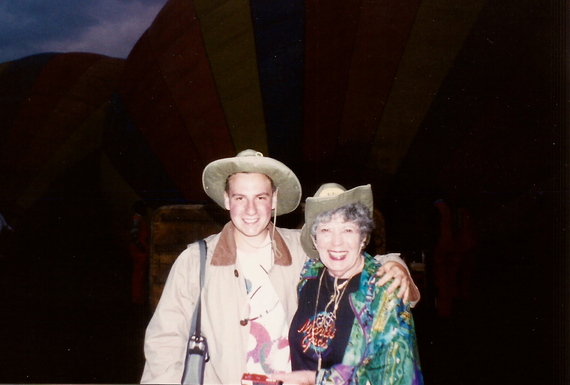

Gram and I prepping for "Broadway Baby" at her birthday party with singing friends, Gregory Ruben and Lauren Thomas

Three months later, a few days before she passed away, she remained witty and reflective. We talked about how challenging it was for her to watch her body fail her. She seemed, uncharacteristically, on the verge of complaining. And then she paused and asked for a touch-up of her lipstick.

The audience and performers at the Daryl Roth Theatre on October 6, 2012 for Mildred's Cabarart: A Celebration of a Life Well Led, including Amy Justman of the recent revival of Company on Broadway and John Arthur Greene of Matilda on Broadway. Gram detested funerals so we organized a performance in her memory instead.

Photo by Thomas Stigler.