Introduction

Quotation marks are used for all citations from Chapter 8 that follows.

The record of the central bank of the United States, the Federal Reserve, on civil rights should be especially important this year, the 50th anniversary of President Lynden Baines Johnson's 1964 Civil Rights Act. The LBJ library that is next to the LBJ School of Public Affairs on The University of Texas at Austin campus will host a Civil Rights Summit. There will be keynote addresses from former President Jimmy Carter on April 8 and former President Bill Clinton on April 9. An invitation has been extended to former President George W. Bush to deliver a keynote address on April 10. (See http://www.utexas.edu/lbj/news/2014/presidents-carter-and-clinton-keynote-lbj-presidential-libra)

There has been extensive gender and racial discrimination at the Federal Reserve uncovered in Congressional investigations that include the Fed's assertion that it is not covered by Lyndon Johnson's Civil Right Act of 1964. Before joining the faculty of the LBJ School, I served as a staff economist assisting in investigations and oversight of the Federal Reserve by Chairman Henry Reuss from 1975 to 1981 and Chairman/Ranking Member Henry B. Gonzalez from 1992 to 1998 of the House of Representatives Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee, now called the Financial Services Committee. The University of Texas Press has given permission to print Chapter 8, "Standing in the Door Against Civil Rights," of my 2008 book, Deception and Abuse at the Fed: Henry B. Gonzalez Battles Alan Greenspan's Bank, on The Huffington Post. Chapter 8 follows this introduction.

It is incredible that the civil rights case I describe in Chapter 8 below continues today in 2014:

"About sixteen African American women filed a class action suit in 1998 against the Federal Reserve, charging discrimination in promotions and salaries. This was a continuation of a case originally filed in 1995 and later dismissed without prejudice. The Fed hired an outside law firm to handle the case. The case wandered on for years through mounds of motions filed by the Fed's attorneys."

The above two cases for these minority women have been in the Federal court system for 19 years. On January 11, 2011 the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit ordered that the case [Cynthia Artis, et al., Appellants v. Ben Bernanke of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Appellee] be "remanded for further proceedings, in accordance with the opinion of the court filed herein this date." (See Robert Auerbach, "Score One Against Racial Discrimination, and the Federal Reserve.")

What happened to six of these female employees of the Federal Reserve when they sued for racial discrimination? They were told to resign and the Fed paid them what they called "career transition pay."

In 2001 I had the opportunity to question two of these women who were part of the lawsuit.

"At a seminar at the National Press Club on January 7, 2001, televised on C-SPAN, I interviewed two longtime Fed employees, one of whom was a secretary to Virgil Mattingly, general counsel to the Board and the Federal Open Market Committee until his retirement in 2004. The employees had sued the Fed for racial discrimination. One of these women said she had been called into an office, informed of her career transition pay, and told to sign a resignation letter. She said that 'the minute you sign the agreement,' you are told to leave, even though the resignation letter is postdated. She added: 'They pay you for not coming to work.'"

Today there are still 14 plaintiffs in the case. Walter Charlton has been the lawyer for the women all these years.

The Federal Reserve hired a large law firm to handle the case. How much did the Federal Reserve pay the law firm to fight these women's allegations of racial discrimination for 14 years? This is taxpayers' money since the Fed sends its income minus the cost of its operations to the Treasury to lower the government deficit.

There are other civil rights cases described below. How much money did the Chicago Federal Reserve spend to get rid of a former vice president?

"A minority person who was a former vice president at the Chicago Fed Bank filed a lawsuit claiming she had been asked to investigate problems concerning minorities at the Fed Bank and that she had come back with the 'wrong' answers. It appeared that the Fed Bank's minority personnel had some valid complaints. The investigator evidently did not use the Fed's usual sweep-under-the-rug technique while waving the independence banner. She was allegedly given the equivalent of a demotion, causing her to sue the bank. The Chicago Fed Bank settled with her for an undisclosed amount. The case did not go to trial, and the Chicago Fed Bank was no longer burdened with a bank official who reported problems with minorities."

"President Johnson made an important move toward diversity at the Fed in 1966. He nominated the first black member to serve on the Board of Governors: Andrew Brimmer, a distinguished economist with a PhD in economics from Harvard. He served for eight and a half years. This nomination established a precedent for having a permanent minority member on the Board."

Unfortunately, this action did not change Federal Reserve diversity as indicated in 1993 when I served again as staff economist, this time assisting House of Representatives Banking Committee Chairman Henry B. Gonzalez. Gonzalez wanted to know how many women or minorities were in top positions at the Federal Reserve. He asked Fed Chairman Greenspan for a list of those Fed employees making more than $125,000 a year. Out of nearly two thousand employees at The Board of Governors, the Fed's headquarters in Washington, D.C., there were only two such employees, a woman and a minority person.

Gonzalez put on the pressure with press releases and numerous speeches on the empty floor of the House of Representative at the end of the day. The critics made fun of Gonzalez talking to the empty chairs, but it was carried on C-SPAN and evoked considerable interest. The Fed's employment policy changed during the next three years. "There were then seventy-two employees earning more than $125,000, and the top twelve earned $174,100. Eleven women and five employees classified as 'minority' were in this group." Included in this group was the head of maintenance for the Fed's several Washington DC buildings, evidently a minority person. His pay was raised to $163,800, higher at that time than the Secretary of Defense.

House Banking Committee Chairman, Henry Reuss worked to end the rampant discrimination at the Federal Reserve in 1977. A Congressional report, shown below states that: " ... the Fed has never had a woman among the 1,042 directors in its 62-year history." Reuss drove the writing of a section of a law shown below that required the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve to stop racial and gender bias in the selection of directors at the their district banks. As a result, Sister Generose Gervais, a well-known Catholic nun, was one of the few women appointed as directors. Perhaps contrary to the Fed's intentions Sister Gervais demonstrated a willingness to speak as a leader during her tenure.

The nomination by President Barack Obama and Senate confirmation of Janet Louise Yellen to be the first female Chair of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve is a needed advance in reducing the continuation of the ninety-six year history of bias at the Federal Reserve since it began operations in 1918.

However, there is much more to correct at the Fed. The first step should be resolving the 19-year continuation of the series of two cases with 14 plaintiffs suing for racial discrimination. What is often said about justice delayed? Determine who ordered and who carried out the orders to fire some of some of these women and give them money to sign predated statements before they were ushered out of the building. Reveal exactly to the nation's tax payers how much money was spent on court cases or used to pay off people who sued for racial or gender discrimination.

The Congress should change the manner in which the Inspector General of the Federal Reserve is now appointed and financed by the Board of Governors, essentially by the Fed Chair whom he/she may investigate. The IG's credentials and views should be made public during a presidential nomination and a confirmation process in the Senate.

Chapter 8, "Standing in the Door Against Civil Rights" below is excerpted from Deception and Abuse at the Fed: Henry B. Gonzalez Battles Alan Greenspan's Bank by Robert D. Auerbach (Copyright © 2008, by the University of Texas Press), used by permission of the University of Texas Press.

CHAPTER 8

STANDING IN THE DOOR AGAINST CIVIL RIGHTS

IT WAS AS IF THE INSTITUTION HAD SLEPT

THROUGH THE 1960S AND 1970S

The Federal Reserve's almost emotional insistence on total independence often leads the Fed into some dark corners. Under Greenspan, the Federal Reserve Board had great difficulty coming to grips with the civil rights revolution. It was as if the institution had slept through the 1960s and 1970s. Alabama governor George C. Wallace's stand in the schoolhouse door in 1963 seems almost enlightened in the face of the Fed's claim of not even being covered by the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

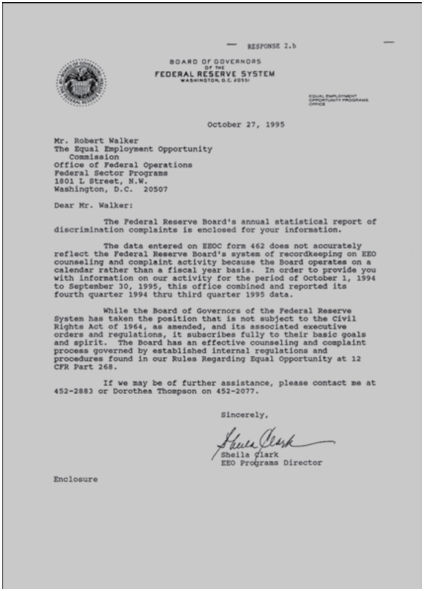

The Greenspan Fed consistently said that it was not covered by this law because of a technicality that, even if true, the Fed did nothing to correct. The Greenspan Fed affirmed that it "subscribes fully to the basic goals and the spirit of the Civil Rights Act of 1964," as shown in a 1995 letter from the director of the Fed's in-house Equal Employment Opportunity Programs Office (Figure 8-1).

FIGURE 8-1. Letter from Sheila Clark, director of Equal Employment Opportunity Programs at the Fed, to Robert Walker at the EEOC, October 27, 1995. Ms. Clark repeats the Fed party line on racial discrimination: "While the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System has taken the position that it is not subject to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ... it subscribes fully to their basic goals and spirit." Source: author's collection.

Greenspan repeated this assertion to Gonzalez in 1996: "While the Board is technically not subject to the Equal Opportunity Act, the Board long ago decided that it should act in strict conformity with the precepts of the Act, which implements national policy."1 That was pleasing rhetoric.

Congressmen Gonzalez and Jesse Jackson, Jr. (D-IL), in a press release and letter to Greenspan in 1997, cited recent legal actions against the Fed for racial discrimination, including one in which the verdict went against the Fed (described below). Contrary to Greenspan's position, they noted: "The EEOC informed the General Counsel of the House Banking committee in 1989: 'It is the EEOC's position that Title VII applies to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.'"2

One month later, Greenspan, while still waving the Fed's independence flag, made a suggestion for amending a section of the 1964 Civil Rights Act so that it would cover the Fed: "The amendment would not affect the Board's statutory independence from other laws respecting federal employment. Accordingly, this proposed change is not inconsistent with the important principle of central bank independence within the federal government."3 If this is what he wanted to do, he should have publicly supported Jackson's legislation that is described below.

The Greenspan Fed's artful dance was all the more incongruous given that the Federal Reserve was charged with enforcing laws to eliminate discrimination in lending by the nation's banks. Not only was the Fed Bank supposed to be a model for diversity in the banking system that it regulates, but it was charged with enforcing specific laws against discriminatory loan practices: the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), which "ensures that all consumers are given an equal chance to obtain credit"; the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA); the Home Mortgage Disclosure Acts; and the Fair Housing Acts.4

For the Federal Reserve, the issue was more than academic and more than a simple case of once again intoning the Fed's independence mantra. A number of civil rights cases have been brought against the Federal Reserve, and several were pending in courts. President Lyndon Baines Johnson and a series of House Banking chairmen had taken actions to bring diversity to the Fed and to end gender and racial bias there in the 1960s and 1970s. Those efforts did not seem to extend into the 1990s. New, abusive management actions--including firing black female employees who sued for racial discrimination problems--emerged at the Greenspan Fed.

LBJ, SISTER GENEROSE GERVAIS, AND JEAN CROCKETT

President Johnson made an important move toward diversity at the Fed in 1966. He nominated the first black member to serve on the Board of Governors: Andrew Brimmer, a distinguished economist with a PhD in economics from Harvard. He served for eight and a half years. This established a precedent for having a permanent minority member on the Board.

A study of the boards of directors of the Fed Banks was begun by House Banking chairman Wright Patman and published in 1976 by his successor, Henry Reuss (see Chapter 2). It found that there were few women or minorities, and little diversity in affiliation, among the 108 directors at the Fed Banks.5 Its findings of racial and gender diversity were close to zero: "Women are ignored totally in the selection of district bank directors and only six women are among the 161 branch directors. Minorities are given little more than token representation."6 Reuss emphasized the clear gender bias at the Fed by comparing its record with another governmental regulatory entity: "The Home Loan Bank Board has appointed six women directors since 1974, while the Fed has never had a woman among the 1,042 directors in its 62-year history" (emphasis added).7 Burns had a catch-22 rationale for the Fed's difficulty in finding qualified women or minorities: few had served on boards of directors in banking and big business, and thus few had the skills needed to serve on the Fed's boards of directors. Reuss retorted: "I must once again disagree with your contention that the talents needed for these boards of directors can come only from banking and big business. ... I cannot accept the idea that there have been no women capable of meeting your criteria for service on the boards of directors of these Federal Reserve Banks."8

The banking industry was well known for its exclusion of women and minorities from all but lower-level jobs. True, it may have been difficult to find women and minorities who had impressive resumes of higher-level jobs in that industry. High-level jobs in the banking industry were not a prerequisite for Fed service: Fed chairman Burns had been an academic. There were female and minority academics who studied central banking, a subject that many who are proficient in private-sector bank management find arcane.

Reuss's leadership and persistence in trying to remedy this problem, spurred on by Burns's seeming determination to preserve the bureaucracy's form of discrimination, led to the writing of one section of the Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977. That section was directed at the three Class C directors on each of the nine-member boards of directors at the twelve Fed Banks. Unlike the other six members on each of the boards of directors, these three members were selected by the Board of Governors, which essentially meant by Burns. The intent was to direct with the force of law that these Class C directors were to be selected "without discrimination on the basis of sex or race, creed, color, or national origin, and with due but not exclusive consideration to the interests of agriculture, industry, services, labor and consumers."

This part of the act had an immediate effect on the insular leaders of the Fed. The late Jean Andrus Crockett served as a director of the Philadelphia Fed Bank from 1977 to 1982, when she was appointed chairperson, the first woman to hold that position at that Fed Bank. She had been a staff researcher for a statistical commission at the University of Chicago, a full professor at the Wharton School (of business) at the University of Pennsylvania, and chairperson of the Wharton Finance Department in 1966. Also, Sister Generose Gervais, a well-known Catholic nun, was appointed to the board of directors at the Minneapolis Fed Bank in 1979.9

Since 1977, Class C directors have included women as well as professionals who had not been officers of businesses or banks.

1990: GREENSPAN AT THE DOOR THAT GONZALEZ

IS TRYING TO OPEN

Soon after Henry Gonzalez became House Banking chairman, he ordered a comprehensive study of diversity at the Fed. The results filled more than 3,200 pages in three books.10 It was clear that the central bank had serious problems. When it came to the boards of directors of the Fed Banks, Gonzalez concluded that there was "a decided lack of minorities and women" and that the Fed "simply ignored those parts of the law which require consumer and labor representatives on the Federal Reserve Boards [of directors]." He said that the "appalling lack of diversity among the 277 [including boards of directors in branches of Fed Banks] directors of the Federal Reserve Banks" was primarily caused by "the Federal Reserve's practice of cultivating a supportive constituency in the banking industry and among big business."11 The Fed Banks were not good models for the nation's banking industry.

Neither was the Fed headquarters. Gonzalez had asked Greenspan for a breakdown of all Board of Governors personnel earning more than $125,000 a year. Out of nearly two thousand employees, the governors had placed only one woman and one minority person in a top paid position. This is shown in a table sent by Greenspan in 1993 (Table 8-1).

A Fed Bank president told his board of directors that the conclusion of the Gonzalez report--that women and minorities were underrepresented in decision-making positions at the Fed Banks--"appears to be biased and not representative."12 This criticism was uncovered in 1992 during a Gonzalez-led investigation of the minutes of boards of directors meetings in Fed Banks. When Gonzalez inquired about diversity, he found an absurd rationale from a Fed Bank president in the minutes of a board of directors meeting, and then cited it in a press release on October 30, 1992: "It is sometimes difficult to find qualified consumer and labor prospects who are not politically active. We find that minorities we wish to recruit are often serving on commercial bank boards which precludes them from serving on a reserve Bank Board" (emphasis was added when the material was quoted in the press release).13 The contention that eligible blacks, Hispanics, and other minorities were already on bank boards, and that qualified consumer and labor prospects were all politically active and therefore ineligible, drew a reaction from Gonzalez that might be called strongly negative: "This is sheer nonsense." He said that the Fed Banks "should stop hiding behind code words such as 'politically active' and admit that they don't want to rock the boat by elevating more women and minorities including persons with a consumer and labor orientation, to decision-making posts" (emphasis added).14

TABLE 8-1 [shown in book]. A SECTION OF THE FED EMPLOYMENT CHART (AS OF MARCH 1, 1993)

THAT GREENSPAN SENT TO GONZALEZ IN 1993*

The Fed could not silence or intimidate Gonzalez. Greenspan and his staff of lobbyists were making the rounds in Congress. Greenspan notified Gonzalez that the Fed had better representation among women and minorities at salary levels below, rather than above, the $125,000 cutoff in Gonzalez's survey. This was an especially poor argument to send to Gonzalez, who would not take lobbying calls or visits from Greenspan unless appropriate action had been taken beforehand. Greenspan, accompanied by several other Fed personnel, lobbied members of the House Banking Committee, explaining the Fed's desire to comply with the spirit of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He did not publicly support any efforts to eliminate the technicality, such as the corrective legislation described below.

The Greenspan Fed had to endure some uncomfortable publicity, and it made some changes. Gonzalez commended the Fed "for some improvement" in 1996, when diversity had improved, but added, "the record is still far from adequate."15 There were then seventy-two employees earning more than $125,000, and the top twelve earned $174,100. Eleven women and five employees classified as "minority" were in this group.

$163,800 FOR THE SUPPORT SERVICE DIRECTOR,

$148,400 FOR THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE

The Greenspan Fed made a bizarre move to elevate an employee into Gonzalez's top salary tier. The Fed increased the pay of what it referred to as the "support services director," whom some others derisively called "the janitor."16 This employee's pay was raised to $163,800, definitely putting him or her among the highest-paid employees at the Fed. This person now made more than a cabinet secretary, who then earned $148,400. Greenspan then drew a salary of $133,600; forty-eight employees earned more than he did.

Asked by an Associated Press reporter why the support services director, who is in charge of maintenance workers at several buildings at the Fed's headquarters, earns more than the secretary of defense, the Fed's spokesman said: "He's got a lot under his wing."17 The Fed spokesman also said that the support services director was far more than a maintenance chief; he oversaw several hundred employees.

COVERING UP REDLINING

Redlining is a practice of discriminating against some loan customers by signaling with a red line drawn under their name in the bank records. With this practice, lenders systematically deny loans to minorities and women. Although actual red lines are probably seldom if ever used now because of antidiscrimination laws, redlining has become a generic name for any type of signaling meant to discriminate financially on the basis of race or gender.

In March 1994, Gonzalez announced some grave allegations about the Fed's examination of banks for bias in lending:

One brave person, knowing of the work I have been doing on the Fed, has approached me with chilling details about unethical conduct taking place at the Federal Reserve. This person is a former Federal Reserve bank examiner who has volunteered to expose gross unethical conduct in the Federal Reserve examination process. The situation had gotten so bad that the examiner decided to quit working at the FED rather than stomach the unethical behavior.

This is a very serious situation which, if system-wide, raises serious questions about the Federal Reserve's commitment to enforcing the Community Reinvestment Act and policing for bias in lending practices.

The examiner said a team of bank examiners documented evidence of violations of the Community Reinvestment Act and bias in lending. The examiner's original report was critical of lending to low-income and minority populations and had noted discriminatory remarks from bank employees about redlining.

The supervisors then replaced the criticism with contrived examples of the bank's eagerness to comply with consumer lending laws.18

THE FED IS SUED FOR RACIAL DISCRIMINATION, REPEATEDLY

In 1994, the Federal Reserve lost a jury trial brought by an African American employee who charged that she had been repeatedly denied promotion because of racial bias. The employee had worked for the Federal Reserve Board of Governors as a senior statistical assistant, providing support to economists. She had been employed at the Fed for more than twenty years. She had sought a promotion to the next category, research assistant, for twelve years. As Gonzalez and Jesse Jackson, Jr., wrote to Greenspan: "She performed many of the same job assignments carried out by research assistants, the main difference being the higher pay of research assistants. Two supervisors testified that she had performed her work better than some of the research assistants who had worked for them."19 Her attorney, William A. H. Briggs, Jr., of Ross, Dixon and Masback in Washington, D.C., reported that she was told by Fed officials that she could not be promoted because she did not have a college degree.20 For seven years she went to night school while working full-time and raising six children as a single parent, and obtained a degree in accounting in 1989.

Again she asked to be given the job of research assistant; but according to Briggs, "she was told that even though she had a degree, she had not taken the right courses." She filed a racial discrimination charge with the Fed's in-house Equal Opportunity Office (EEO). A settlement was reached that "essentially provided her with a list of courses she had to complete."21

When she "re-applied for the same position in 1992, she was interviewed by a woman who was named in her first EEO-complaint. She was again turned down for the job as she was told that others were better-qualified for the position, even though she already preformed many of a research assistant's duties."22 The Fed's runaround, including the farce with the Fed's EEO, ended when she sued again.

She won the case when "a federal jury in Washington found that she was denied the promotion because of her race and then retaliated against for filing an EEO complaint."23 Federal District Judge Ricardo Urbina ordered Greenspan to retroactively promote the employee and to give her back pay and $150,000 in compensatory damages. Attorney fees were paid out of the $150,000.

About sixteen African American women filed a class action suit in 1998 against the Federal Reserve, charging discrimination in promotions and salaries. This was a continuation of a case originally filed in 1995 and later dismissed without prejudice. The Fed hired an outside law firm to handle the case. The case wandered on for years through mounds of motions filed by the Fed's attorneys. A continuation of the case was still in the courts in 2007.

Some of the women were "invited" to resign with a payout that the Fed dubbed "career transition pay." Congressman Jesse Jackson, Jr., said; "I have received information that six of these women have left the Board of Governors and were given 'career transition pay' consisting of two years' salary provided they do not return to employment at the Board of Governors."24

At a seminar at the National Press Club on January 7, 2001, televised on C-SPAN, I interviewed two longtime Fed employees, one of whom was a secretary to Virgil Mattingly, general counsel to the Board and the Federal Open Market Committee until his retirement in 2004. The employees had sued the Fed for racial discrimination. One of these women said she had been called into an office, informed of her career transition pay, and told to sign a resignation letter. She said that "the minute you sign the agreement," you are told to leave, even though the resignation letter is postdated. She added: "They pay you for not coming to work."

Despite this altruistic-sounding name--career transition pay--this compensation amounts to nothing more than a bribe in exchange for an employee's signature on a resignation letter or possibly for an employee's dropping of a lawsuit. The Department of Justice and the courts should determine if these Fed actions regarding plaintiffs suing for racial discrimination are legal. Did the Fed chairman's words to Gonzalez in 1997 cover the longtime Fed employees whose career transition was to the street outside the Fed: "Of course, under the Board's well-established policy, persons who participate in any administration or judicial proceeding relating to allegations of unlawful discrimination in employment must not be subject to retaliation."25 Similar racial discrimination cases were filed against the Chicago Fed Bank. In 1998 it was reported that: "Eight present and former employees of the Chicago Fed Bank sued. They charged that they had been subjected intentionally to unequal and discriminatory treatment because of their race and color."26

A minority person who was a former vice president at the Chicago Fed Bank filed a lawsuit claiming she had been asked to investigate problems concerning minorities at the Fed Bank and that she had come back with the "wrong" answers. It appeared that the Fed Bank's minority personnel had some valid complaints. The investigator evidently did not use the Fed's usual sweep-under-the-rug technique while waving the independence banner. She was allegedly given the equivalent of a demotion, causing her to sue the bank. The Chicago Fed Bank settled with her for an undisclosed amount. The case did not go to trial, and the Chicago Fed Bank was no longer burdened with a bank official who reported problems with minorities.

The costs to the Fed and the nation's taxpayers of this type of settlement to employees and payments to private law firms should be clearly specified in a detailed and clear budget that can be examined by the House and Senate Banking Committees. Congress should request the Fed to show where in the Chicago Fed Bank's accounting records the settlement is specifically identified. The amount should be public, so taxpayers can see where their money goes.27 The Banking Committees should also be given the original report of the former Fed official.

STOPPING THE FEDERAL RESERVE CIVIL RIGHTS

COMPLIANCE ACT OF 1999

Despite some court findings, Greenspan continued to contend that the Federal Reserve was not subject to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Angered by the Fed's repeated denials of discrimination, which flew in the face of trial records and the continuing cases brought by employees, Congressman Jesse Jackson, Jr., introduced legislation mandating that the Federal Reserve post signs to notify its employees of "applicable provisions of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964" legislation.28 Jackson immediately gained twenty-four cosponsors for the legislation, but then the power and political muscle of the Greenspan Fed came into play. Greenspan's lobbyists descended on Capitol Hill.

One source described the reaction in Congress.29 The recruiting of cosigners slowed, and then the chairman of House Banking [now called the Financial Services Committee]--Jim Leach--did not sign on to Jackson's legislation. And John LaFalce, who had just replaced Henry Gonzalez as ranking Democrat on the committee, declined to cosponsor. When asked about the failure to sign Jackson's legislation, Leach reportedly said he had "no plan to investigate the Federal Reserve's personnel practices while the cases were pending in Federal courts."30 LaFalce simply declined to respond to inquiries. In the Senate, neither Banking chairman Phil Gramm nor ranking Democrat Paul Sarbanes (D-MD) appeared interested in Jackson's legislation or the Fed's repeated claims of being exempt from the Civil Rights Act.

THE GREENSPAN FED IN WONDERLAND

The Greenspan Fed's denial of the applicability of the Civil Rights Act to itself may have seemed harmful, but the Fed's retreat on fair lending on December 23, 1996, also damaged equal rights. While everyone was preoccupied with the holidays, the Greenspan Fed took a giant step back on fair lending. At issue was a proposed rule to end the Fed's longstanding ban on the collection of data on the race and gender of applicants for small-business and consumer loans. The data, community and civil rights groups contended, were critical for revealing discriminatory lending patterns and for enforcing the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA). But the Greenspan Fed turned its back on this issue, justifying its inaction with a garblement that was in a class with its monetary-policy announcements:

Ultimately, there is no easy way to measure the extent to which discrimination occurs in credit transactions, nor the effect the rule has had on the incidence of discrimination. It is impossible to know precisely how, if at all, lifting the prohibition and making these data available would affect creditors' actions. On the one hand, it is likely that the prohibition has helped to prevent discrimination in at least some credit transactions. On the other hand, creditors have collected data in connection with mortgage loan applications for nearly twenty years, and there is no indication from this experience that data collection increases the potential for discrimination.31

Every governmental agency involved in loan programs--the Small Business Administration, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Agriculture Department, to name just a few--collects data on race and gender as an important tool in making certain that there is equal access. More to the point, the Federal Reserve was already required to collect race and gender data on loan applications under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA). These data have proven invaluable in efforts to spotlight discriminatory lending and enforce the ECOA.

APPEARING WITH CIVIL RIGHTS LEADERS

Although the media had largely ignored the racial discrimination lawsuits and a federal jury in Washington "found that [a Fed employee] was denied the promotion because of her race and then retaliated against for filing an EEO complaint," Greenspan deserved and received favorable civil rights coverage for his actions in 1998. Greenspan walked with Congresswoman Maxine Waters, chair of the Congressional Black Caucus, through her district in South Central Los Angeles. Several days later, Greenspan and other celebrities appeared with the Reverend Jesse Jackson, who was promoting an effort to bring greater diversity to financial firms, at a three-day conference on Wall Street.32 Greenspan's appearances were certainly helpful in bringing attention to the need for investment in South Central Los Angeles and for shining a spotlight on the need for diversity in Wall Street firms.

CHAPTER 8 END NOTES

1. Greenspan to Gonzalez, October 29, 1996, 3; author's collection.

2. Gonzalez and Jackson, press release and letter to Greenspan, March 6, 1997; the quotation is from the letter, 2; both in author's collection.

3. Greenspan to Gonzalez, April 14, 1997, Attachment II; author's collection.

4. The quote is from the Federal Trade Commission Web site: http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/conline/pubs/credit/ecoa.shtm.

5. Three of the nine directors--the Class C directors--at each of the twelve Fed Banks are appointed by the Board of Governors. The other six directors are elected by the member banks (private commercial banks) in the district. The Federal Reserve Act stipulated that these six directors were to be elected in two groups: three Class A directors were selected from banks, and three Class B directors were selected from industry. The composition of the boards mirrored the composition of leaders in the banking industry, white males.

6. House Committee on Banking, Currency and Housing, Federal Reserve Directors, 5.

7. Reuss, press release, June 10, 1976. A note from the Fed's congressional liaison, Don Winn, showing the dissemination of this press release to the Fed's governors is in the Burns Collection at the Ford Library. It may have annoyed them to find that they had been urged to "live up to the [Federal Home Loan Bank Board's] FHLBB'S example," as Don Winn reported in his attached memo.

8. Reuss to Burns, August 30, 1976, 1.

9. For information on Jean Andrus Crockett, see "Jean Andrus Crockett, Professor: Led Philly Federal Reserve," Wharton Alumni Magazine, Spring 2007; available at http://www.wharton.upenn.edu/alum_mag/issues/125anniversaryissue/crockett.html. For information on Generose Gervais, see Jeff Hansel, "Sister Generose: Hands and Heart for God," Rochester (MN) Post-Bulletin, May 28, 2007; available at http://search.live.com/results.aspx?FORM=DNSAS&q=news.postbulletin.com%2fnews manager%2ftemplates%2flocalnews_story.asp%3fa%3d295641%26z%3d2.

10. House Committee on Banking, Finance and Urban Affairs, Status of Equal Employment Opportunity at the Federal Reserve: Diversity Still Lacking, Part 1 (1,100 pages) and Part 2 (1,001 pages); and A Racial, Gender, and Background Profile of the Directors of the Federal Reserve Banks and Branches (60 pages). A wider view of federal banking agencies is reported in House Committee on Banking, Finance and Urban Affairs, Problems with Equal Employment Opportunity and Minority and Women Contracting at the Federal Banking Agencies: Hearing before the Committee on Banking, Finance and Urban Affairs (1,163 pages).

11. Racial, Gender, and Background Profile, viii.

12. Quoted in a press release by Gonzalez, October 30, 1992; author's collection. Gonzalez noted: "One of the minutes I received [from a Fed Bank board of directors meeting] stated that a Federal Reserve president told his directors on September 14, 1990, that the Banking Committee's August 1990 staff report entitled A Racial, Gender, and Background Profile of the Directors of the Federal Reserve Banks and Branches 'appears to be biased and not representative.'"

13. Quoted in ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Press release, "Rep. Henry B. Gonzalez Finds Only Slight Progress in Diversity in Hiring at the Federal Reserve," August 21, 1996, 1; author's collection.

16. Karen Gallo, "Fed Doubles the Number of Staff Making Over $125,000 A Year," Associated Press, September 11, 1996. The headline for this story in the Washington Times (front page, September 12, 1996) read: "Where a Janitor Earns $163,800, Federal Reserve Defends Big Salaries."

17. Ibid.

18. Henry B. Gonzalez of Texas, "Reduction in Regulatory Control of Federal Reserve Board Is Subject to Proposed Legislation," statement on the floor of the House, March 9, 1994, 103rd Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 140: H 1140. Gonzalez asked the Fed's Inspector General "to insure that no retaliatory actions are taken against examiners who have reported unethical behavior." Given the IG'S reticence to look into Fed Bank matters when asked to do so by Gonzalez, this request was probably futile.

19. Gonzalez and Jackson to Greenspan, March 6, 1997, 1; author's collection.

20. Bureau of National Affairs, "Race/Retaliation; Black Woman Denied Job at Federal Reserve Awarded $150,000, Promotion for Race Bias," Employment Discrimination Report 3, no. 17 (November 2, 1994), 3.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Bennett v. Greenspan, Dt. D.C., C.A. No. 93-1813-RMu; filed April 20, 1993; decided October 17, 1994.

24. Jesse Jackson, Jr., "Federal Reserve Board Civil Rights Compliance Act of 1999 Introduced" (press release), July 1, 1999; available at http://www.jessejacksonjr.org/query/creadpr.cgi?id=579.

25. Greenspan to Gonzalez, April 14, 1997, Attachment 1, 2; author's collection.

26. "Discrimination at the Fed," Nader Letter, January 18, 1998, 9.

27. All money the Fed does not "need" is sent back to the U.S. Treasury.

28. Jesse Jackson, Jr., press release, July 1, 1999.

29. "Discrimination at the Fed," Nader Letter, January 18, 1998, 9. Ralph Nader was assisted by Jake Lewis, who served on the House Banking staff for twenty-seven years and before that was a reporter in Texas.

30. Ibid.

31. Federal Reserve, Board of Governors, press release, December 23, 1996; available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/press/boardacts/1996/199612233/.

32. The conference included a speech by President Clinton.