Writing in the Huffington Post two weeks ago, Michael Kaiser, the doyen of arts management, raised an alarm for arts criticism, arguing that the Internet is undermining the arts field. Kaiser wrote, "one of the substantial changes in the arts environment that has happened with astonishing speed is that arts criticism has become a participatory activity rather than a spectator sport," adding that this kind of participation is, "a scary trend." Someone once wrote that critics are "a grandstanding, depressive and histrionic bunch," and that seems doubly true for Internet critics, who have roasted and lambasted Kaiser for his commentary.

Responses have been published locally (as in the Washington City Paper arts blog), and far afield (as in the UK Guardian). Andy Horwitz blogged that, "Kaiser's article reflects how out of touch many in the arts establishment are with the reality on the ground," and Ian David Moss blogged that "rather than pine for the good old days, we [should] accept these new voices." The editorial board of the New York Times might be on Kaiser's side, however, because in a special section published December 2010 titled Why Criticism Matters, the Times' editors and contributors highlighted a number of considerations echoed in Kaiser's piece.

The Times' section includes an introduction by the editors and six articles by author/critics. The introduction notes, "We live in the age of opinion -- offered instantly, effusively and in increasingly strident tones. Much of it goes by the name of criticism, and in the most superficial sense this is accurate." Respondent Stephen Burns contributes, "the audience now talks to itself."

Each essay in some way seeks to define criticism. Burns describes a critic's capacity to provide "vertical framing," "to ascertain where a work fits into the contemporary and historical field," and a "horizontal map," considering "intellectual currents in other disciplines that have informed or challenged the work under review." Respondent Pankaj Mishra cites Cynthia Ozick's summary: "The key is indebtedness. The key is connectedness." Reflecting on Kaiser's -- and the New York Times' -- concerns, the question remains: even if they're right about what's being lost, why does it matter?

Intuitively one might agree with Kaiser when he asserts, "great art must not be measured by a popularity contest," but isn't it true that great art reflects the ideals and inspirations of people today? What's wrong with a knee-jerk reaction to art? What's wrong with popularity?

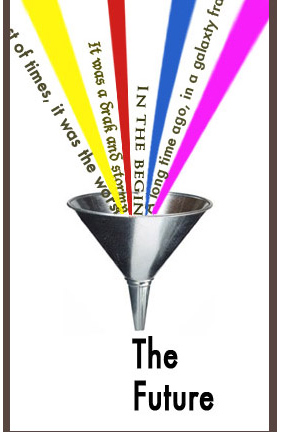

This topic quickly becomes massive. Essentially: art and criticism are facets not only of culture, but of civilization. While culture is in many ways guaranteed, civilization is not, and critics are part of an ecosystem that (hopefully) encourages the existence of ideas benefiting humanity and civilization. Francis Galton coined the phrase "nature versus nurture" to consider the influence of heredity and environment on human development, and the concept can be appropriated to consider the role of critics in supporting the best achievements in the arts. What "we" think about art is conditioned, and art critics have for centuries played a role upholding a limited meritocracy in the field. In his 1985 classic, The Cult of Information, Theodore Roszak argued that "most of our master ideas about nature and human nature, logic and value become so nearly subliminal that we rarely reflect on them as artifacts of the mind," or as influenceable entities. But tastes are influenceable, and the reflexive impact of changes in the field of criticism on the arts field concerns many (including Michael Kaiser, and the editors of the Times.)

The new media seems able to sustain an impressive (oppressive?) amount of coverage, but coverage and criticism are two very different things. If tomorrow's culture is to be informed by the best traditions of today, we need now additional mechanisms to support good arts writing.

A writing career is an increasingly entrepreneurial endeavor, and it would be valuable for the field to identify and support young writers of merit (over young writers with popularity, or youthful business savvy) early on. The market for journalism is broadening, and early identification of and publication for talented writers will impact career success.

One such mechanism is the D.C. Student Art Journalism Challenge. Created in 2010 by the D.C.-based arts magazine Bourgeon, the D.C. Student Arts Journalism Challenge is a competition for undergraduates in District area colleges and universities that encourages and identifies emerging talent in the field of arts journalism. The competition is free to enter, and the submission period for the 2012 competition opened December 1, 2011 and will close February 15, 2012. With support the program will expand next year to include D.C. high school students. Unfortunately, financial support for the competition has been hard to find.