NFL drafts come and go.

Football legends remain.

When Tom Parr, longtime football coach of Hopkins, one of the oldest prep schools in the country, retires on June 14, the ghost of Walter Camp, father of the modern game of football, will hover nearby in New Haven, Conn.

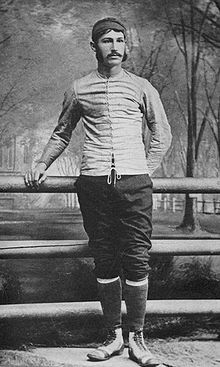

Camp, a graduate of Hopkins, which was founded in 1660, later studied at Yale, where he not only captained and coached the Elis starting in the late 1870s, he essentially invented football as we know it today. He devised the line of scrimmage, which revolutionized the sport from its origins as a rugby scrum. He introduced the down system, the number of players on each side of the line of scrimmage, the idea of penalties, the quarterback position, and of course the concept of the gridiron itself.

Parr, who coached at Hopkins for thirty-three seasons, may not have invented the game, but he turned around a program that was accustomed to losing, and he made it a perennial power in the Fairchester League.

Under Parr's leadership, the Hilltoppers won 206 games and lost 74. The winningest coach in Hopkins football history, Parr led the school to seven league championships, four New England prep titles and four undefeated seasons.

Parr never produced any pros or NFL draftees, but the very first professional football player, according to tradition, was Pudge Heffelfinger, a lineman at Yale, who traced his roots back to, you guessed it, Walter Camp.

On June 14, Hopkins head of school Barbara Riley will present the Hopkins Medal, the school's highest honor, to Parr, a man whose accomplishments go far beyond his wins as a coach.

Like Walter Camp, who instilled in generations of young men the values of integrity, courage and what was then referred to as "muscular Christianity," Parr has stressed to his troops the importance of "true teamwork, sacrifice, loyalty to players next to you, sportsmanship," as he mentioned over the phone on April 27.

He has ably fulfilled Hopkins' original mission: to foster the "breeding up of hopeful youths."

Besides providing lessons about leadership, Parr has also taught his players the proper techniques of the game, in particular the proper tackling technique. That may be one of his greatest legacies, given the acute dangers posed by the sport.

"The most important thing was safety," Parr said.

"Andrew (Levy) and those guys," he added, speaking of one of the starting linemen from his first Hopkins team, the 1982 squad, "they counted more than the game." Parr said that if you don't protect your players, "you have no business in coaching."

While some coaches are only now starting to focus on safety issues, Parr never allowed his players to lead with their heads. He always taught his players to put their "face in the football" and "shoulder into the body."

Parr's laurels come at a time when football has been battered by negative publicity. The NFL bungled the Ray Rice case, one of many domestic violence scandals involving pro football players in the not too distant past. Aaron Hernandez, recently convicted of murder, is only the latest example of a football player who has been implicated in homicide and other felonies.

Some commentators, notably Keith Olbermann, have called for a boycott of the upcoming NFL draft due to the league's failure to take a hard stance against players who have committed spousal abuse or domestic violence, among other crimes.

Dan Barry's front-page column in the New York Times' sports section on April 27 about Patrick Risha, a former Dartmouth running back, whose life spiraled out of control and ended with suicide, illustrated another peril of the sport. Near the end of that piece, a post-mortem on Risha's brain revealed that he had chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain condition associated with repeated head trauma.

It is the same condition that was found in the brain tissue of NFL greats Junior Seau, who also committed suicide, and Mike Webster, to name just two former players.

Football apologists have tried to downplay these tragedies as isolated ones, but no one can deny the inherently violent nature of the sport, not Walter Camp, not Tom Parr.

Studies show that repeated head trauma from football, as well as other contact sports, can lead to neurological disorders such as CTE, ALS, Alzheimer's and other illnesses.

This past week, a federal judge approved a multimillion-dollar settlement to a class-action lawsuit between the NFL and thousands of former players. The lawsuit accused the NFL of concealing the detrimental effects of concussions on the long-term health of players.

Way ahead of his time in emphasizing safety, Parr had a rule that he would minimize hitting at practice. "We were always thin in depth," he said, so we would "hit dummies, hit bags, practice form tackles" during the week.

Other coaches now employ similar safety measures, but Parr, showing great foresight, did this for thirty-three years at Hopkins. The result was not only a record number of wins but also very few concussions.

Don Bagnall, the head trainer on the football squad since 1982, spoke of the precautions Tom Parr took for the players.

"The kids' welfare always came first, physically and mentally. It was always in the forefront."

Bagnall let his son play four years for Coach Parr. "With the proper coaching, the proper equipment, the proper medical staff," Bagnall said, the risks of the game can be mitigated.

Of Parr's legacy, Bagnall referred to "the amount of mental preparation" Parr brought to the game. "His practice plans, especially his game plans. He just outcoached the opposition."

Despite all of Parr's preparation and his emphasis on safety, Bagnall mentioned that one Hopkins player endured a serious head and spinal injury on the field. That student did not play football again, but he made a full recovery from spinal stenosis, according to Bagnall.

Over the past thirty-three years, some Hopkins players did get their "bells rung," a somewhat affectionate football term that does not convey the potential severity of a single concussion.

Andrew Levy, a veteran of the 1982 squad, who squared up against bigger linemen, said that he and Dave Amendola, a star on that offensive and defensive line, may have experienced minor concussions. But that was not due to the way they were coached. It was due to the brutality of the sport.

Parr recognizes the dangers of football and said that its future may be "different" from anything we can anticipate. He pointed out that the rules are already changing. For instance, he said that players are supposed to be penalized with flagrant fouls when they lead with their head. That does not mean that those rules are always enforced.

Walter Camp would have endorsed Parr's approach and would likely have approved of the new rules. After all, he originated the notion of penalties, and he played a major role on the football rules committee, authorizing changes in the game, until his death in 1925.

While pro football, in spite of its recent controversies, gained top Nielsen ratings this past season, even President Obama, a fan of the sport, stated that, if he had a son, he would have to think "long and hard" as to whether he would let him play the game.

Such caution is not new.

In the early 1900s, more than one hundred years ago, Walter Camp led a delegation to the White House to advise President Teddy Roosevelt about football, which then, as now, was known for its barbarism.

Players back then wore minimal pads and head gear.

Unfortunately, helmets, which were designed to improve the safety of the sport, have not infrequently been used as a weapon to ram opponents.

When we spoke over the phone, Parr said that in addition to the changes in the rules, he is hopeful that manufacturers can design safer helmets.

But the key again is teaching the proper tackling technique. Parr, who has three sons, said that he never hesitated in encouraging them to play football.

His son, Gary, rushed for approximately 225 yards in a 28-21 victory over Tabor Academy, a team with linemen in the 300-pound range, for the New England championship in 2000, one of Parr's favorite moments as a coach.

While Parr has had great success at Hopkins, his career did not begin auspiciously. His squad in 1982, his debut year, had a record of 1-5, scoring only 25 points all season, 13 of them against South Kent, the team's only win.

At the time, Hopkins often played schools with a much larger enrollment and in some cases with post-graduate students.

The 1981 Hopkins team, which went 1-6-1, faced Avon Old Farms, where Edwin Esson, a former Parade All-American at Seymour High School and one of the leading rushers in Connecticut history, spent an additional season as a post-graduate. According to Andrew Levy's best recollection, Esson rushed for some 200 yards without even playing the fourth quarter, as Avon trounced the Hilltoppers that day.

That was not atypical of the kind of opponent Hopkins faced back then. Kent, Taft, Suffield and other schools with big-time football programs often overpowered the Hilltoppers.

When Parr took over in 1982, Hopkins suffered to an extent from an absence of what some have characterized quaintly as "school spirit."

It was not that there had been no good football teams at Hopkins in the years just before Parr arrived. The 1980 squad, coached by Tyler Chase, had a 4-3-1 record. That team featured two of the best backs in Hopkins' history: Teddy White, known for his spin moves, who retired as Hopkins' all-time leading rusher and played college ball at the University of New Hampshire; and Phil Stanley, one of the speediest track stars among schoolboys in Connecticut, who later captained the basketball team at Tufts.

There were some Saturdays when White and Stanley each topped 100 yards rushing.

More often than not, though, the Hopkins squads of the late 1970s and early 1980s struggled to win games.

As a college preparatory school committed to "the breeding up of hopeful youths," Hopkins has always been known for its academics.

Over the course of its long history, the school has graduated such luminaries as Walter Camp; composer Charles Ives; Colonel House, an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson; and John Malone, the telecommunications pioneer. (Full disclosure: This reporter graduated from Hopkins in 1983.)

But school spirit often derives from the success of a sports program. And football, more than other sports, typically sets the tone at the scholastic and collegiate levels.

Back in 1982, the football program at Hopkins was languishing. But it was about to undergo a renaissance that would restore it to a luster worthy of Walter Camp.

Andrew Levy, who runs Wish You Were Here Productions, a sports marketing agency based in New York, started as an offensive and defensive lineman on Parr's 1982 squad.

Since he graduated from Lehigh University in 1987, Levy has served as a marketing agent for professional athletes, coaches and managers, arranging personal appearances, product endorsements and speaking engagements. He has also sold sports memorabilia, highlighted by the auctioning of Don Larsen's uniform from his perfect game in the 1956 World Series.

Over the years, Levy has worked with and/or represented hundreds of sports figures, such as Ottis Anderson, a Super Bowl MVP; Walt Frazier, a two-time NBA champion with the New York Knicks; David Cone, a five-time World Series champ and Cy Young Award winner; Goose Gossage, a Hall of Fame reliever and World Series champ with the New York Yankees; and Joe Torre and Joe Girardi, Yankee managers past and present.

Though he works regularly with Hall of Famers, Levy all these years later remains impressed with Coach Parr.

"Before we even knew him, we thought, 'here's this All-American quarterback from Colgate, who coached at Jonathan Law, a public school with some tough kids, a big-time football program. Why? Why does he want to come here to coach football's version of The Bad News Bears?'"

Right away, Coach Parr introduced "a lot of structure" with morning and afternoon workouts in August, to which the team was unaccustomed.

Exercises as simple as the timed one-mile run left captain Rich Ridinger and other veteran players like Seth Stier "puking" on the first day of practice.

Andrew Levy, upon finishing the run, felt tingling and numbness in his right hand. He thought he was having a stroke and as a result got an MRI at Yale-New Haven Hospital, which revealed that he had nothing more than a migraine.

As a precaution, Coach Parr, always emphatic about player safety, then excused Levy from all the remaining workouts.

When he returned to practice, Levy beamed and, in reference to his time in the one-mile run, boasted to his teammates, "Six minutes, fourteen seconds! And excused from double sessions!"

If that 1982 squad consisted of a bunch of lovable losers, Parr never let his players feel that they were other than winners. He inspired them, as he would inspire his championship teams, with his work ethic, his loyalty and his dedication to the scholar-athlete ideal, all of which came through in his speeches.

While Walter Camp, who had a penchant for alliteration, originated terms such as All-America (the precursor to today's All-American) and Daily Dozen, the fitness regimen he created for out-of-shape servicemen preparing for World War I, Tom Parr has likewise demonstrated a way with words.

Before the first game of the 1982 season, Parr called the players into the coaches area in the back of the locker room.

Levy recounted the moment, which was told at a reunion banquet by a teammate, Jason Lichtenstein. "We squeezed in there. And it stinks. There's no ventilation, and he gives this very motivational Knute Rockne-like speech, but he tells it in a soft way. Then at the end, he screams, 'How far?' We yelled, 'All the way!' Then he screamed, 'Gonna quit?' and we yelled, 'No way!'"

That call-and-response became one of Coach Parr's signature Parr-isms.

Other Parr-isms have included, "Success is not a destination, but a continuous journey," a Zen-like adage that sounds familiar to those who remember the Nike commercial about life being a journey, not a spectator sport.

That some of the Parr-isms have had a familiarity to them has not detracted from their wisdom.

The most famous Parr-ism, according to Levy, was another call-and-response routine that evoked an old saying about boxing champ Joe Louis, who was said to be a credit to his race, the human race.

Parr's formulation went as follows: "It's a great day for a race!" Parr would yell.

"What race?" the players would shout.

"The human race!"

Levy summed up Coach Parr's philosophy with a story Parr told at the football banquet at the end of that 1-5 season in 1982 and that Levy repeated in 2007 at the 25th anniversary celebration of Parr's career at Hopkins.

As befits a Zen master, Parr told a parable about an optimist and a pessimist. The pessimist is upset about receiving a Rolex watch for Christmas, whereas the optimist rejoices in receiving manure.

Why? Because the optimist knows, he just knows, that somewhere, around the house, gallops a new horse!

As Levy said at the 25th anniversary celebration, "Coach Parr, on behalf of the senior class of 1983, your inaugural season, we are proud to have been your manure, and we congratulate you on finding your horse."

Dave Amendola, the star of that inaugural squad, later captained the football team at the University of Connecticut where he played for coach Tom Jackson. In his senior year, Amendola led the Huskies to the Yankee conference co-championship with an 8-3 record, including a 5-0 mark at home.

Amendola, who stood at 6'3" and weighed close to 250 pounds when he suited up for Hopkins, was extremely quick for a man his size. Though he may not have played in the pros, Amendola was a pro-caliber lineman, who, Parr said, may have been the best player he ever coached.

Amendola grew up in the 1970s, roaming the sidelines as a ball boy for the Yale Bulldogs. He spent years under the tutelage of his late dad, Buddy, a longtime defensive coordinator for Yale football guru Carm Cozza, who reigned as dean of Ivy League coaches from 1965 to 1996.

Buddy later headed up the program at Central Connecticut State University.

When asked to compare Parr to all the football masters he observed in his day, Amendola said, "He's right there with the legends. He changed me dramatically, transformed me from an adolescent to a man."

Amendola, who was named most improved player at UConn when he was a sophomore, would also win the Yankee conference player of the week award a few times.

"It all started with him (Parr) molding us at Hopkins."

A father of three, Amendola has a 14-year-old son, who played a bit of youth football. But Amendola has not encouraged his son to play the sport because of its inherent violence. "Unless he gets the killer instinct," said Amendola, he does not want his son out on the gridiron. He is glad that his son, who is 6' 4", is focusing for now on tennis and basketball.

Like Amendola, Tom Parr did not make it into the NFL. But he too was a pro-caliber player even if he stood only 5' 9 3/4". An ECAC all-star at Colgate during his senior year in 1973, he was joined in the All-East backfield that year by John Cappelletti, the Heisman Trophy winner, and Tony Dorsett, who won the Heisman a few years later.

A speedster and an escape artist, Tom Parr ran the 40 yard dash in 4.6 seconds. "You didn't see a lot of 4.4's back then," he said.

That Tom Parr was an outstanding runner links him once again to Walter Camp.

Camp was not only the founder of the game, as well as its greatest strategist and coach with a record of 67-2 at Yale; he was also a gifted running back. While he was alive, Camp was often compared to Odysseus, primarily because he was such a fleet and evasive runner, like the Greek hero from Homer's epic poem, The Odyssey.

Perhaps, it is poetic justice that Parr hails from Ithaca, though he grew up in upstate New York, not Greece.

His father was a great quarterback as a young man, and so was Parr, who began playing when he was around 12 years old.

He turned down West Point to go to Colgate, where he quarterbacked the Raiders for three seasons.

The Raiders, who won the NCAA title in 1932 and have a rich football heritage, going back to the 1890s, had a middling record while Parr led the squad. The team had slightly more wins than losses during that time, compiling records of 6-4 in 1971, 5-4-1 in 1972, and 5-5 in 1973.

Even if the team did not win any titles while Parr was a student, he excelled on the playing field. He led Colgate to a 55-21 victory over Lafayette to open the 1973 season. In that game, Parr rushed for three touchdowns and passed for four more, setting a Colgate record for most combined touchdowns that stands to this day.

Parr was named the Associated Press' Back of the Week for his performance.

He was profiled in Sports Illustrated under the headline, "No breaking this Parr."

The subhed read, "Colgate's Tom Parr, an unlikely looking quarterback, makes an inviting target, but every time he gets hit, he bounces up to set another record."

Following that record-setting game, Lafayette coach Neil Putnam told the Telegraph, a paper based in Nashua, N.H., "Tom Parr is the finest option quarterback I have faced. He possesses the size, speed and skill to run the wishbone offense and does so with perfection."

Parr was one of the top rushing quarterbacks in the nation in the early 1970s. He ran for 2,200 yards in his three years, a total that nearly equaled his passing yardage of approximately 3,000 yards. When he was a senior, he rushed for 833 yards with eight TDs. He averaged 6.5 yards per carry, which was the tenth best mark in the nation in 1973.

He also finished tenth in the country in total yards (rushing and passing combined) with 1,960 in 1973. And in 1972, he finished seventh in total touchdowns (rushing and passing) with 21.

In his final game as a collegiate player, Parr led the Raiders to a 42-0 rout over Rutgers, a team that had whipped Colgate the year before.

Parr, who called his own plays much of the time in high school and college, remembered that final game. He scarcely ran the ball in the second half. Knowing that the scouts were watching fullback Mark Van Eeghen for the East-West Shrine Game, "We kept feeding Mark and feeding him."

Van Eeghen played well in the Shrine game and had a fine pro career. He surpassed 1,000 yards rushing for three consecutive years (1976 through 1978) in the NFL. He was a key player on the Oakland Raiders in the 1970s and early 1980s, starring on Super Bowl-winning teams in 1977 and 1981.

Yet in 1972, Parr, a modest man who rarely talks about his own accomplishments, actually ran for more yardage than Van Eeghen.

Parr's former coach at Colgate, Neil Wheelwright, left no doubt as to who was the best player on his team.

After Parr's record-setting game against Lafayette to open the 1973 season, the Telegraph of Nashua, N.H., quoted Wheelwright as saying this of his star quarterback: Parr "is the finest player I've ever coached. He's a perfect option quarterback because he conceals what he's going to do until the last moment and then he'll either beat you by running, passing or giving the ball to a back."

Mark Van Eeghen, whom I phoned on April 30, agreed with Coach Wheelwright that Parr was "without a doubt" the best player on the team.

"He was so far before his time," said Van Eeghen from Providence, R.I., where he works in the insurance industry. "The quarterbacks coming out now with their mobility and shiftiness, run and pass, that was Tom all the way. That was the epitome of him."

Van Eeghen, who speaks with a trace of a New England accent, added that Parr "had that confidence, that swagger, that twinkle in his eye in the huddle. He was a calming influence on the team, the coach on the field."

Like Parr, Van Eeghen is an extremely modest man. He led the AFC in rushing in 1977 when he finished behind Walter Payton for the league rushing title.

Unlike many former players, Van Eeghen has experienced neither cognitive decline, nor any debilitating injuries from playing football.

That is not to say that he did not get his bell rung a few times. "You can't play in the NFL as a fullback for ten years" without taking some hits, he said.

Running behind linemen Gene Upshaw and Art Shell, Van Eeghen and tailback Clarence Davis romped through the Minnesota Vikings' famed Purple People Eaters in Super Bowl XI. Van Eeghen also played well in the Raiders' Super Bowl victory in 1981 over the Philadelphia Eagles.

During his years with Oakland, he teamed in the backfield with two outstanding pro quarterbacks, Kenny Stabler and former Heisman winner Jim Plunkett.

While Van Eeghen was reluctant to compare Parr to them, he did note that Stabler "couldn't run, but he could dissect a defense, had a much better arm."

Plunkett likewise had a strong arm, but he could not run well.

Of Parr's passing, Van Eeghen said that "Tommy didn't have a chance to show his arm," because he ran the wishbone so effectively.

If Parr played today, Van Eeghen said, "he goes in the first round, no later than the second round."

Dan Hurwitz, a 1982 graduate of Hopkins, just missed playing for Coach Parr, but he did go on to play at Colgate for four years. The starting center on the 1981 Hilltopper squad, Hurwitz considered transferring to Jonathan Law High School in Milford, Conn., where Tom Parr coached before he came to Hopkins and where he was a colleague of Hurwitz's mother, a teacher.

"I almost transferred to Jonathan Law, just to have a chance to play for Coach Parr," said Hurwitz from his office in New York, where he runs Raider Hill Advisors, a real estate investment firm.

Asked about Parr's legacy as a coach, Hurwitz said that Parr "was equally concerned, if not more concerned, with having a positive impact on the players, as he was with winning."

Hurwitz, who until recently was CEO of DDR, a Cleveland-based real estate firm, characterized football as "an all-encompassing life lesson."

Although a recent Bloomberg Politics poll indicated that 50% of American parents don't want their sons to play football, Hurwitz said that he had no reservations about letting his own son play.

And Hurwitz, a soft-spoken man with an imposing presence, still raved about the sport. "I use everything I learned on the football field every day in life. That includes being part of something bigger than yourself, relying on others, them relying on you, being a winner graciously, and losing graciously."

As for the sport's risks, Hurwitz said that football "has always been a physical game." He added that at least now there is "a sensitivity to the issue, people getting proper treatment, paying attention to the issue of head trauma."

When asked what made Parr special, Hurwitz kept using the word "impactful." Hurwitz said that Parr "was impactful as a player, he was impactful as a coach, he was impactful as a teacher, and he was impactful as a mentor."

Parr, who as a player at Colgate competed against some tough Yale squads in the 1970s, was joined on the sidelines in 1982, his rookie year as Hopkins head coach, by, among other assistants, Delaney Kiphuth, then 64 years old and Yale's athletic director from 1954 to 1976.

During his tenure as Yale A.D., Kiphuth hired Carm Cozza, who became the winningest football coach in Yale history over his three decades of helming the program at Yale Bowl.

Like Tom Parr, Kiphuth was a legend in his time. He famously gave Calvin Hill a pep talk when Hill was considering quitting the Eli squad in the late 1960s. Hill would later win the NFL's offensive rookie of the year award as well as a Super Bowl with the Dallas Cowboys.

One of the kindest yet fiercest of men, Kiphuth stood only five-foot-six or so and weighed about 150 pounds, but he was a starting lineman for Yale in 1940, not long after Larry Kelley and Clint Frank earned Heisman trophies as stars on the Elis.

That Tom Parr began his career at Hopkins with Delaney Kiphuth at his side means that Parr had a direct connection to Walter Camp, whom Kiphuth and his father, Bob, Yale's fabled swim coach for four decades, knew and revered.

To give the modern reader a more complete understanding of Camp's significance in the history of the game, consider what Knute Rockne, Notre Dame's most celebrated coach, said after Yale decimated the Fighting Irish when Rockne was a graduate assistant in South Bend.

As Rockne put it, "The Notre Dame shift came from Yale, and Yale got it from God."

That God of course was Walter Camp.

Besides influencing Rockne, a deity at Notre Dame, Camp trained and mentored other football icons like Howard Jones, who pioneered the football program at USC, turning the Trojans into a national powerhouse in the 1920s.

Camp's most famous disciple was Amos Alonzo Stagg, who, among other innovations, conceived of the huddle, introduced the tackle dummy for practice, and devised numerous offensive tactics such as the lateral pass, the reverse play and the man in motion. He retired with 314 collegiate coaching victories, still one of the highest totals in the annals of the sport.

When asked whether he views himself as a disciple of Walter Camp, Parr, who in addition to coaching has served as athletic director at Hopkins for nearly three decades, said that "you're blown away with the tradition."

Parr, a former history teacher, noted that Camp was "captain of his house team at Hopkins" in 1872, just a few years after the very first football game played between Rutgers and Princeton, back when football more closely resembled soccer or rugby.

Parr, who ran the option out of a wishbone formation when he was at Colgate, used an "I" formation and a split backfield as coach at Hopkins. As he said over the phone, "we were run-oriented," with an emphasis on running "off-tackle." He pointed out that Hopkins sometimes competed against schools that were better and physically bigger than the Hilltoppers, teams like Brunswick. "You try to control the ball, to shorten the game."

When asked why he is retiring at the age of 63, Tom Parr said that he is a "dinosaur," a bit of a Luddite, who does not necessarily love the way technology has changed what it means to be an educator. He also has been "coaching in a lot of pain" for some time. He has Factor V Leiden's Mutation, which makes him "susceptible to blood clots."

As far as what he plans to do, Parr said, "For 51 years, I've played or coached from August through November. It will be nice to take a fall off."

He would not rule out a return to coaching. And he said that he may want to go back to fund-raising as well.

Asked about his legacy, Parr said, "Hopefully, I've carried that tradition (of Walter Camp) on. You hope you've had a positive effect on people."

He added, "You wanted to make it so kids liked to come to practice. You wanted to inspire kids so they didn't want to let you down. "

Rocco DeMaio starred as a wide receiver and tight end on Parr's first four squads. DeMaio has served on Parr's staff for more than two decades, has been the head baseball and basketball coach at Hopkins over the years, and is currently the head golf coach at the school.

He played tight end and wide receiver at Trinity College in Hartford, Conn., before returning to Hopkins as a coach.

Now a candidate for athletic director at the school, a position Parr has long held and will be relinquishing on June 14, DeMaio said this of Parr's impact on his life and career, "He was like a father figure, a second father figure for so many of the players."

DeMaio, who refers to Coach Parr as Tom, spoke of the life lessons that Parr imparted to the students, such as the need for mental toughness. "To a 16 year old, it didn't really sit with me," but the messages at the end of practice, the motivational speeches at different points in the season, later began to resonate with DeMaio, particularly in his 23 years as an assistant to Parr.

"I appreciated it more and more as I got older," said DeMaio.

After Parr would speak at the end of the year to the seniors, "which was always a moving experience," DeMaio would get up there and tell them, "I'm the luckiest guy in the room. For you, it's your first time (hearing Coach Parr), but for me this is my fifteenth time or my twentieth time."

DeMaio, 47, still marveled at Parr's stamina. DeMaio said that "after a long practice," he would often "shake his head, looking at the energy" of his mentor.

DeMaio also confirmed Parr's long-held commitment to player safety. Because Hopkins is a relatively small school with only 700 students, DeMaio said, "We're still able to regulate how much hitting we do during the week." And he said that Parr always stressed tackling with the shoulder, never leading with the head.

DeMaio added that, as an educator, he has learned "a lot about the brain. It's made me think about it (football) deeply."

He has a seven-year-old son. Like Dan Hurwitz, DeMaio said that he would let his son play football.

Sandy MacMullen has been the head lacrosse coach at Hopkins since 1979. During that time, he has also served as an assistant football coach. A lacrosse star at Yale, MacMullen was part of Parr's initial brain trust at Hopkins and was a close friend of Delaney Kiphuth, after whom an award has been named for the best history student at the prep school.

MacMullen e-mailed me about Parr's impact on the young men he has coached. A history teacher, who comes from a family of educators and athletes, MacMullen thinks of significant, historical figures in terms of a "ripple effect" over the generations. "Influential people are that largely because of the ripple effect they cause. Small actions can create larger ones and bigger consequences," he wrote.

In his e-mail, MacMullen did not emphasize Parr's championships, which are well known. Rather, MacMullen wrote about Parr's adages and life lessons. "From the simple 'do your homework' that was part of every single post-game talk to players, to 'don't make this moment the biggest one of your life' before the final game for the seniors, to 'success is a journey, not a destination,' spoken often to all, Tom has given guidance for behavior that carries far beyond a football field."

Barbara Riley, head of school, has overseen Hopkins for about 15 years. Like Parr, she too will be leaving soon, in her case at the end of the next academic year.

During her stewardship of the school, Riley has seen the lives of so many "hopeful youths" enhanced by Tom Parr. Needless to say, she was heavily involved in the decision to award the Hopkins Medal to Parr.

"Given to the person who has shown unprecedented loyalty, commitment and devotion to Hopkins School," the Hopkins Medal, Riley said in a phone interview on April 30, has "seldom" been awarded to a member of the faculty and staff. It is usually reserved for alumni, trustees, or parents of students at Hopkins.

Asked about Tom Parr's legacy, Riley spoke of "the intangible stuff that is so embedded in Hopkins' culture," intangibles such as a dedication to the scholar-athlete ideal and sportsmanship. That culture, she said, has filtered "through osmosis" into the lives not only of Parr's players but also the lives of students who did not play for him and into the lives of many of the other coaches at the school.

Like Walter Camp, whose influence extended far beyond the football field to all the team sports at Yale and around the country, Parr became "the dean of athletic directors in the (Fairchester) conference and beyond in New England."

Riley said that one can not measure Parr's impact simply by numbers of titles and wins and yards. She said over the phone, as she did in a letter to the Hopkins community, that the numbers that truly matter are "the hundreds and hundreds of Hopkins boys, many of whom believe - know - that the most important and lasting part of their Hopkins experience came with learning from and playing for Coach Parr."

Besides serving as head of school, Barbara Riley, like Sandy MacMullen, Delaney Kiphuth and Tom Parr, has taught history at Hopkins. She is steeped in the life and career of Walter Camp, perhaps the school's most illustrious graduate.

When asked what Camp would say about Parr's upcoming honor, Riley cited so many parallels between the two men: the "intelligence, order, strategy and sportsmanship" that both brought "to a game that can too often be driven by other, lesser qualities."

She added that for "both Walter Camp and Tom Parr, integrity and fair play were their watchwords."

Parr's final season as Hopkins' football coach was his worst in terms of the team's record. At 1-7, the 2014 squad equaled the 1982 squad for fewest victories by a Parr-coached club.

The team still worked hard in practice, played clean football and competed every week.

Reflecting on Parr's approach to coaching and the mental strength he cultivated in his Hopkins players, Andrew Levy, one of the leaders of that 1982 squad, said, "If you go out on a football field without confidence, you're not only going to lose; it's dangerous. He made us feel we were a lot better than we were...And then we still went out and got our butts kicked!"

With all the controversy surrounding football, particularly as it concerns long-term health problems from concussions, the sport may not have a future. Whether it does or does not, Tom Parr has always taught his players to play the game the right way. He has enriched the lives of hundreds of young men, and he deserves credit for restoring competitiveness to a football program that dates back to Walter Camp.

Parr, who long proclaimed that "the road to the championship runs through New Haven," clearly belongs in the pantheon of New Haven coaching heroes.

No one should doubt that Walter Camp's spirit, which at one time was missing from Hopkins, will haunt the campus in New Haven on June 14.

It will be like Odysseus returning to Ithaca.

The football gods will be happy.

Correction: A previous version of this article indicated that Mark van Eeghen led the AFC in rushing in 1978 and that he was a few yards behind Walter Payton for the league rushing title. Van Eeghen led the AFC in rushing in 1977 when he finished behind Walter Payton for the league rushing title. Van Eeghen trailed Payton by a few hundred yards, not a few yards.