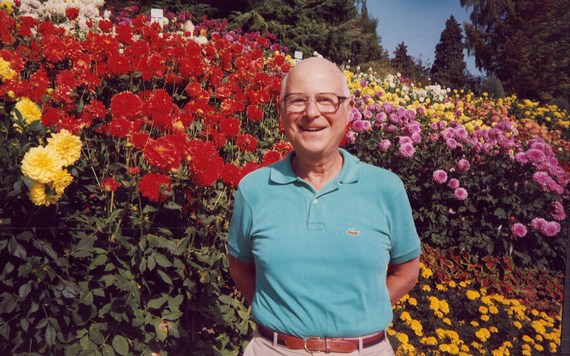

We had the memorial service for my dad, Ed, on Sunday. He'd passed away a week earlier, about six weeks before his 95th birthday. This was the eulogy I gave.

*

When my father had his 90th birthday, he said he was shocked because he never expected to get that far. So, every year to him was a bonus. For me, it turned out more problematic -- because after having given speeches for him to celebrate his 50th wedding anniversary, 80th birthday, 60th anniversary, 90th birthday, I really don't have much else left to say. But realized that I could at least start by doing something few people get to do at their own memorial service -- let my dad speak for himself.

Years ago, my dad wrote a memoir, which was actually quite good and, not surprisingly, very funny. But it was the wonderful writing that stood out, because my dad wrote very well.

Though he was a great doctor for over half a century, and loved with pride at being referred to as "doctor" -- always correcting people when called "Mr. Elisberg" -- he didn't come from a family where being a doctor was the obvious first choice. His father Mike and Uncle Harry were tailors, making ladies garments. Elisberg Originals was the company. That was the family business. In his book, my dad explained why it didn't turn out to be his business:

"I was born to the purple," he wrote. "Velvet, lining, buttons, yard goods. When I reached the age of consciousness, I realized that manufacturing women's clothing wasn't for me. So I spent my childhood playing with chemistry sets, threatening to blow up the neighborhood, and establishing the fact that I had no head for business.

"It was decided by the brain trust," he continued, "namely my mother and father, that it would be prudent to keep me far away from anything with yarn. As a result of this momentous decision that changed the course of history (mine), the mantle of succession fell on my brother Richie's shoulders, an act for which he probably and deservedly never forgave me."

Of all the jokes he tells in this chapter about tailors, however, my favorite isn't really a joke at all, but rather a true story.

By way of background, acquaintances would always come to the shop, believing that they'd get a special deal that way: perhaps a cheap price on a "new Dior" that they were told by my grandfather was just off the boat, shipped from New York to be copied," or a "Balenciaga" or other "French designers," not ever knowing two things -- one (as my father wrote), that "nothing French ever got closer than 8,000 miles of that showroom" and two, that the only rule that existed there was, "Don't let them get away without buying."

On this particular day in question, my father had to fill in at the shop, answering telephones. He wrote of that memorable experience:

"Late one afternoon," he writes, "a very prominent rabbi came to the factory, to buy the clothes for his family of a wife and two daughters, and I could hear the transaction. I guess the rabbi did the buying on the mistaken idea that nobody would possibly take advantage of a man of God. That might have been true in other places, but I doubt it was ever valid in the Garment Center Building, where he was dealing with another breed of men of the cloth. Anyway, even he too was shown all the 'Diors just off the boat' and 'Balenciagas' and a whole horde of 'French designers', and so the rabbi bought and bought. Maybe he knew what he was doing. I hope so. It may go better for my father in heaven.

"When we closed for the evening, I said that I would take public transportation home, and my father could drive alone. He wondered why I'd want to do a thing like that, since he always drove me. I told my father that if there was a God in heaven who might have been listening to his pitch to the rabbi, he would never make it home alive, and I didn't want to be with him when a bolt of lightning sent down by the Almighty hit the car."

And so my dad got home safely -- did not go into the clothing business -- and became a doctor.

It wasn't that he was such a great doctor, as most of you here know. It's that he loved being a doctor. Absolutely loved it. Instead of watching television, his entertainment was reading medical journals. For fun, he read electrocardiograms. I'm not exaggerating.

Here's how much he loved being a doctor -- when he had his quadruple bypass surgery several years back, he said that outside of normal vacation days off, it was the first day of work he had missed in 39 years. He always went to the office, even if he wasn't well.

There's actually some remarkable proof how much he utterly loved being a doctor. I'll get to that in a few moments at the end. It's worth the wait.

But it wasn't just that he loved being a doctor. I always got the sense that his patients loved him. I say that because growing up, when strangers would hear my last name, their first response was often, "Elisberg? Are you Eddie's son?"

I'm not exaggerating about this, either. Only a couple years ago, I was at a friend's house in Los Angeles for New Year's Eve. It was crowded, and I got introduced to someone's wife, who it turned out was from Chicago. "Elisberg?" she asked. "Are you related to Eddie Elisberg?" It turns out that she and her mother had both been nurses at Highland Park Hospital. And she added how wonderful she thought he was.

I was never bothered being known as "Eddie's son." To have so many people acknowledge you because of how wonderful your father was -- that makes a strong impression of deep admiration.

What I loved most was the kind of doctor he was. All he cared about was getting a person well. He believed in all that medicine could do -- but if a body could heal itself, he felt it best to get out of the way. The job wasn't to show how great he was, the job was to get the patient healthy.

And I was in awe that he was an innovator, as well, having articles written about him. Decades before businesses discovered this, his office staff was full of incredibly talented women who'd left the profession to raise a family, but later wanted to get back to work, or could only give a half day on occasion. So, he had the most qualified people he could find. He didn't care who was there, he only cared that they were good. My mother referred to them as "His Ladies."

At his and my mother's 50th anniversary, I gave a speech and went on at length about all this. And when I was finished, the first words I heard were from my dad, yelling out across the crowd, "You never said what a great father I was!!"

I had sort of taken that for granted, but as a result of that, a few years later at his 80th birthday, I gave my shortest speech ever. I got up and said, "He was a great father" -- and then sat down.

And he was. I go on about him as a doctor because I think so many people can say how terrific their father was, but he was unique as a doctor. But I've always known that my brother John and I were lucky to have had him for our father. He was supportive, loving, not overly outgoing but Midwest taciturn, solid as a rock, funny, caring of others, and set among the greatest examples for honesty and decency as a child could want. And perhaps the greatest example he set was how he adored my mother.

I'd like to pause a moment to fulfill a promise.

When my mother passed away, there was a memorial service that was wonderful and so-pleased my father. He loved it. Except for one thing. A few weeks later, in a heart-broken voice, he said that the service was moving and terrific, but the one thing that never got said was "how beautiful Betty Lou was." And then he went on, "She was a beauty queen, you know. She was so beautiful." And so I promised him that when I spoke at his funeral I would make sure to say how beautiful my mother was. And I have kept my promise.

It was of course a very difficult time for my dad when my mother passed away after 66 years of marriage. But there was one good thing to come from her very long hospitalization. It was going in with him every day and seeing so close up how much he absolutely adored her. Every day, month after month, he'd sit by the bed and -- this quiet, taciturn man -- opening up with endearments, endlessly. I won't begin to repeat them, because I wouldn't get through it, but "Eddie loves you, you know that, don't you?" will forever be a happy part of my being.

I'm coming to the end pretty soon, but it's important to note a few things about my dad.

I have to note that he was the definition of a loyal football fan. It's one thing to follow a team that's good. But he had season tickets for 49 years to Northwestern, the team with literally the worst record in the history of college football.

He grew up blocks from Wrigley Field and walked to games as a little boy. I remember my first game with him there, against the Milwaukee Braves. He passed along his love of the Cubs, which some people might hold against their parent, but I'm thrilled for it. After all, this could actually be the year... And I'm so glad he got to see them playing so great this year and remarkably in first place. He loved it.

I'm also glad that when he and my mother moved to Glencoe, his brother, my Uncle Richie, moved only blocks away. So we got to grow up living close to Aunt Joan, and my cousins Susie and Steve. And I'm grateful for them and Dick still staying close after all the years. And my mother's relatives, the Levitons.

And I have to continue expressing my deep gratitude to the wonderful, remarkable Elizabeth Fernando for being one of the angels on earth. Far more than a caregiver. She told my dad she wouldn't ever leave him - just as she'd said to my mother - and she was always there...always there... even beyond normal expectation. And I'd like to thank Elizabeth's family for sharing just a part of her.

Finally (which is one of the happiest words to hear at a eulogy), I want to get back to what I'd mentioned earlier. There are many people who can say that they always wanted to be a doctor. My father is one of the few who can actually prove it. And not just prove it, but do so in a way that shows that everything wonderful he did with his life is merely something that he said he would always do, and he lived up to his word -- and his heart.

When my father was only 10 years old, he wrote a poem. His father was so impressed with it, that he had it printed up in a little pamphlet that he gave out. And I have a copy here. As I began today reading from my dad's own words as an adult, I'd like to close with his words, too, as a child. But they stood as his core his whole life.

It says - "Written by Edward I. Elisberg. June - 1931."

I Want to Be a Doctor

By Edward I ElisbergI want to be a Doctor

to get over runnin' away

From all the dreadful accidents

that can happen in a day

To give when someone's in distress

A kind and helping hand

To help the sick and wounded

Stay upon this land

To assure when hope is dying

That everything's alright

That all is going splendid

He'll be better in a night.

I don't want to be a doctor

on account of pretty nurses

I don't want to be a doctor

Just because of rich men's purse's

And the thought from my mind is far

To be a doctor just for the D-R

I want to be a Doctor

to keep all people livin'

I want to be a Doctor

so I'm always always givin'

But the real reason from the beginning

in my mind has stood

I want to be a Doctor

To do the world some good.Edward I. Elisberg

Age 10

*

To read more from Robert J. Elisberg about this or many other matters both large and tidbit small, see Elisberg Industries.