The invention of screenwriting software was one of the great Eureka moments for writers. (This is a group, by the way, that includes not only professional writers, but also the hugely-growing world of hopeful college screenwriters and even huger world of would-be closet screenwriters with their Great Story to tell.) That moment took all of the bizarre and near-incomprehensible conventions of screenplays and automated them. This began with a product called Scriptor, created by Stephen Greenfield and Chris Huntley, which was so revolutionary that the Motion Picture Academy awarded them a Technical Achievement Award in 1994 for their contribution to the creative process.

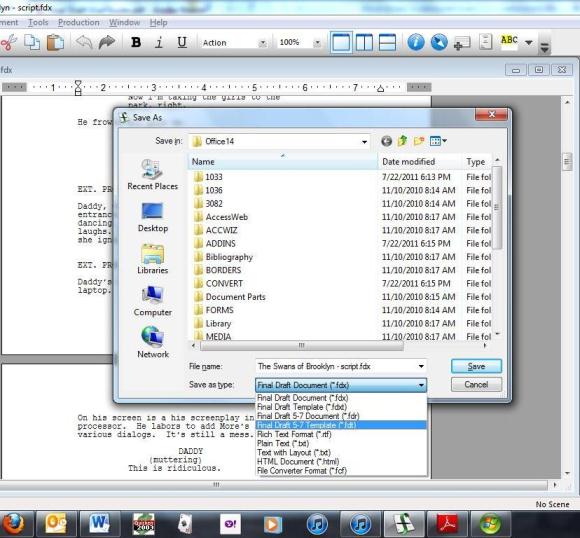

Scriptor worked by first writing the script with one's regular word processor (such as Microsoft Word) and then the program's software formatted the work. It was wonderful, though still a bit convoluted. This all changed when standalone word processors entered the picture. You just wrote your screenplay, and it was instantly formatted. One of the first was ScriptThing, created by Ken Schafer for Windows. Another, Final Draft, was developed for Macs.

As the Scriptor company expanded with other products, it recognized that its core "conversion" software was outdated. They researched what they thought were the best programs on the market, and teamed up with ScriptThing. Adding their own improvements, the resulting product was Movie Magic Screenwriter.

In time, the unwieldy marketplace has winnowed itself down. While other competing products exist, including some free options, the two big elephants in the room today are Screenwriter and Final Draft, both of which now work on either the Windows or Mac format.

And so it is that we now look at those two. Which is The Best?

Before diving into the details, here's the big secret that's been true for many years:

Both programs work very similarly. Both programs are excellent. Both programs are widely used in the Industry. And both programs can read documents written by the other, once they've been very easily saved first to .RTF format.

And this is the follow-up codicil: whoever you ask which program is best will tell you whichever one they personally use.

But still, there are very real differences that stand out, the proverbial "bells and whistles," and ultimately that's where devil resides, in the details.

Movie Magic Screenwriter

Final Draft

Dedicated screenwriting word processors today are loaded with impressive features, but first and foremost, before getting to anything else, the core function is simply typing and formatting your script. That's the cake; everything else is icing. Hamlet, after all, was written with a quill.

If you've figured out how to hit the Tab and Enter key, you've come close to mastering Screenwriter. Yes, there's a lot more to it, but that covers the basics. Hitting ENTER moves you between most Elements (like jumping to a new Scene Heading or Action, or moving to the Dialogue margin after typing a Character Name), while hitting TAB will move the cursor directly from Action (for instance) to the start of a Character Name. That's pretty much it.

By the way, once you've typed in a character's name, it will be remembered, so when you start typing it a second time a list will pop up with all names that begin with that same first letter. (A feature they call QuickType.) You can then just highlight the character you want and hit ENTER without typing anything more.

QuickType also will enter Scene Headings and Locations similarly. When you type the first letter in a Scene Heading margin, previously-used locations will pop up with that same letter, and get culled down as you keep typing. ("EXT. HO..." will pop up both "House" and "Home" if you've already used them both. Typing a "u" next will leave only "House" to choose from)

The program also provides a shortcut for when you have dialogue in a scene between just two characters: rather than hitting "Tab" and having to enter the characters' name each time, using SHIFT-TAB instead will automatically insert the name of the last character who spoke, without you having to type anything. (This feature is the default in Final Draft - a nice touch since many scenes are two-character only, though less ideal for all your scenes with three or more characters in them.)

When you're in the Dialogue Element (to type dialogue, of course), entering a left-parenthesis will automatically indent margins for a parenthetical comment.

It's all extremely easy. But then, "extremely easy" is the default rule with Movie Magic Screenwriter.

Writing tools

Though most everything in Movie Magic Screenwriter is configurable, the core point of the product is to work seamlessly without any user input, other than the pesky chore of having to enter words on a page. (Customizable is great - not having to customize is even better.) For instance, Scene Headings are all automatically capitalized, as are character names and transitions (like, DISSOLVE TO:)

(Note: there is a known issue in the program when you type the "FADE OUT:" transition. It sometimes works fine, but occasionally appears as "FADE OUT\FADE OUT:" It's not a problem, since it's easy to manually type in again, though it can be a bit disconcerting when it first happens)

One of the best "ease-of-use" features of the software is that it knows where to break the end of pages, particularly in dialogue, while then adding "MORE" to the bottom and "CONTINUED" at the top of next page, and re-adding a character's name where the dialogue re-starts. And if you change a page, it knows to reformat all this once again, instantly.

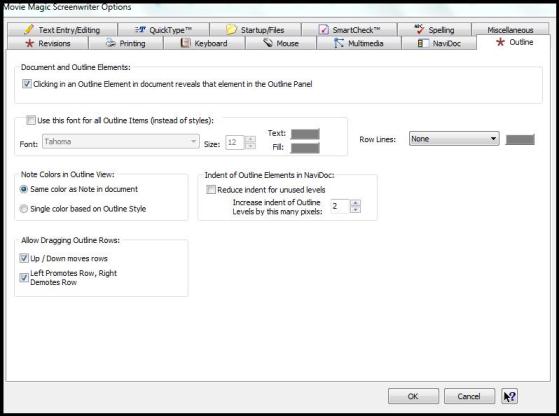

To be clear, that's somewhat standard for these kinds of programs - Final Draft does it, as well - but Screenwriter makes it very easy to change all formatting to your personal preferences. For instance, if you want to leave "CONTINUED" off at the bottom of every page, you have that option. If you want there to be a single blank line between scenes rather than two lines, it's your choice. In fact, most everything is configurable, which is one of the program's great strengths. And it's not only changing the formatting to any way you want, but you can change much of how the program itself actually operates and even appears - what lists will pop up, changing how certain key combinations (like Ctrl-Delete) will function, re-size text to make it more readable yet without affecting the page count, or even display text on screen in one font that you happen to prefer to read, but have it printed in another.

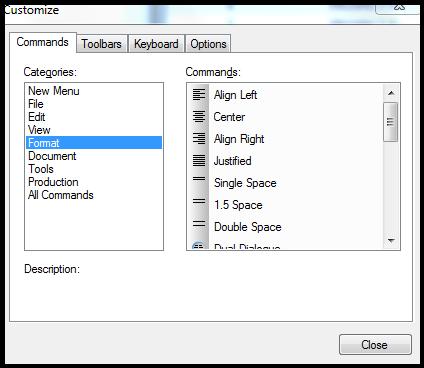

For that matter, you can change how the keyboard works. For example, you can make it so that hitting ENTER while in the Action Element will jump you to the Character Element (rather than the default use of the TAB key). In fact, not only can you add or remove button icons and toolbars - you can get rid of all icons, all toolbars and the rulers completely, and have just a blank window. And there's so much more that can be changed: however you want everything to run and look is largely up to you.

And it's all quite easy to do so. Formatting a script, as one example, used to be one of the most head-banging annoyances of typing a screenplay (outside of, perhaps, oh...plotting and character development...). Now, however, if you have a script formatted exactly the way you like it (the margins and line breaks and use of "CONTINUED" and such), you can create a template directly from it. Similarly, you can change the program's default template to a style that uses one of your existing scripts. Simply load your script and select "File/Save as template." That's it. From then on, whenever you want to start a new script, it will use this format style. Yet if you want several different formats, depending on the script (or TV show), you can create as many formats as you want.

Speaking of templates, the program includes ones from 86 different TV series. Though this is of limited value to most people, they also include blank templates for screenplays, TV, stage plays, radio, and comic books. There are even sample script templates for different styles of movies, as well as an "instructional template," which might be the most valuable of all, since it gives you a hands-on way of learning the program as you scroll through the script.

For all these available options to configure the program almost any way you want, often in multiple ways for the same function, there's one odd omission. Despite having 51 toolbar icons you can choose for a wide-range of actions - there's no icon for closing a file. There is the default Windows "x" on the far right, which will close your document, and you can always use the menu, but nothing on the main toolbar.

Among the range of bells-and-whistles for the writing process, the program has an updated thesaurus and dictionary that allows checking of individual words, pages or Elements. Most notably, though, in addition to the program's standard dictionary, a second dictionary - the excellent third-party WordWeb - is also built in, which you can run separately. (Word Web is a standalone dictionary/thesaurus that I've been using in my regular word processing for years.)

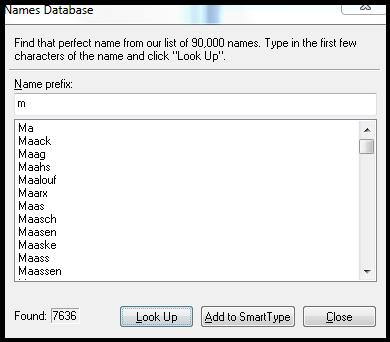

MMS has a Name Bank that could be of use for helping decide on character names. It only has a third the number of names as Final Draft, however it organizes them better, conveniently breaking names down into three tabs for male, female and surnames, rather than one long list.

One of the nicest features is its "Cheat" tool. This pops up a box that lets you adjust a margin or line spacing, as well as format the fonts. Final Draft has a similar feature called "Leading" which manages line spacing a bit easier. But "Cheat" is far more encompassing, letting you not only also deal with margins (letting you spill over a line by a single word - or even a comma), but also can fine-tune text by as little as tenths of points.

A helpful touch is being able to create a PDF file from within the program and then directly email it, either as that PDF file or in the native Screenwriter file format (so that the recipient can work on the file). Also, the title page creator is extremely simple to use, locking it in before the beginning of your script.

The NaviDoc

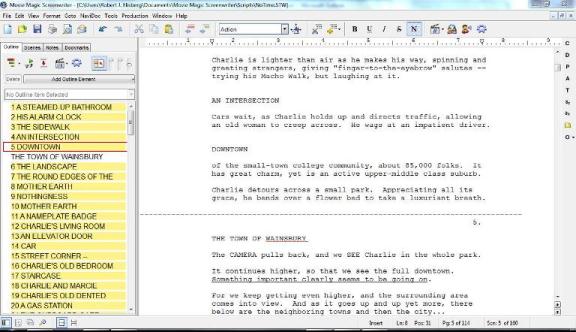

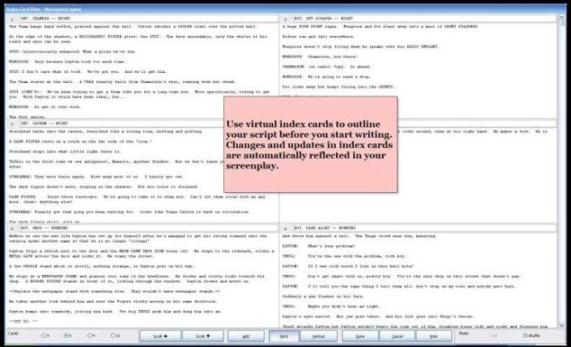

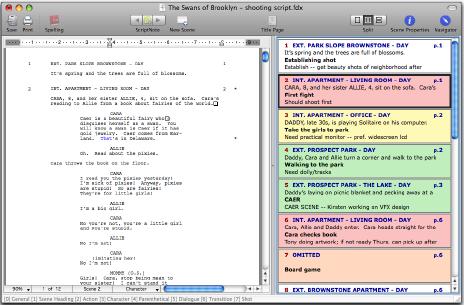

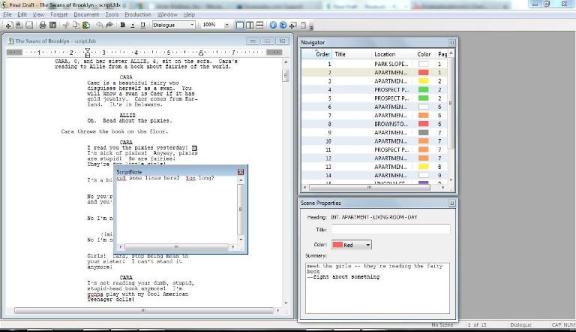

The most noteworthy writing feature is the wide-ranging NaviDoc, which is sort of an all-in-one tool for navigating through your script. The NaviDoc can be locked so that it's always on a split-screen with your screenplay, or hidden it until you want to access it. It allows you to create an outline for your screenplay, manage the script through a list of scenes, write notes and embed them within your script, and make bookmarks. Each of these is easily accessible from clear, separate tabs in the NaviDoc.

(To make the NaviDoc disappear, you "grab" its outer edge with your mouse and drag it in towards the side of your monitor. I'd have preferred it having a "x" box to click for closing, but that's not particularly significant. You can also open and close it by with keyboard command or the menu bar.)

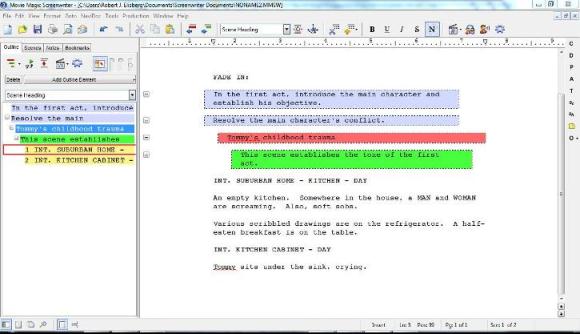

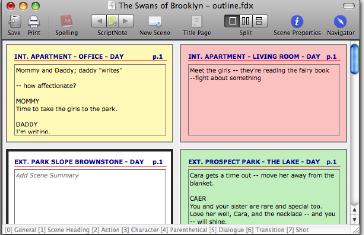

With the Outline View, you can create an outline from scratch - or an outline will be built automatically in the NaviDoc window as you type your your script in the main MM Screenplay window. (The program knows how to convert a script's Acts, Scenes, and Shots into outline form). If you do choose to outline from scratch, there are numerous built-in templates you can choose from, including "Classic Film Structure," "BBC screenplay for TV" and templates even for musicals, radio, novels, and comic books. You then can write your script using the outline template as a guide. Scenes can be move by drag 'n dropping them in the outline.

In the NaviDoc, the outline will appear in a list format, but with a click you can change this to look like index cards. (Or toggle back to the list.) And in Index Card View you can decide how many "cards" will appear on screen at a time.

I'm an "analog guy" when it comes to the outlining process and use a pen for that, so I didn't find the outline feature all that beneficial, but for those who prefer to digitize the whole process, it works very well and powerfully. What's nice is that you can click on anything in the outline, and it will jump directly to that location in the script (once the script is written, of course).

As for the aforementioned Index Cards, they're fairly plain, with no way to coordinate them by color. You have two ways to handle cards - a button toggles between Shuffle mode (letting you drag scenes around) and Edit mode. Shuffling is an excellent feature, though it's a little convoluted to use (and doesn't compare to the ease of shuffling real cards. It's easier to move scenes in the outline than from the card view.) The terrific thing about Edit mode is that whatever you write in an index card shows up directly in the script - and vice versa. A very important missing feature, though, is the ability to click on a card and jump directly to that scene in your script. This limits the usability of index cards more than would be preferable.

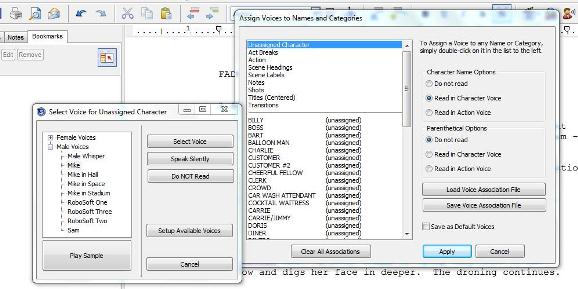

More useful (for me) than outlining is the Scene View tab. As you write your script, every scene and shot is automatically created in the NaviDoc. Similar to Outline View, clicking on a scene will jump you to that location in the script. What's nice is that you can organize how the scenes are listed in Scene View, and it won't affect how the scenes appear in the script. For instance, if you want to see all interior scenes together, or want scenes listed by location or by time-of day, just click the "Sort Scenes" button in the NaviDoc. Again, this only changes how they're listed in the NaviDoc, not in the script itself.

Note View is another very valuable feature of the NaviDoc. It's highly customizable, but like much of Movie Magic Screenwriter, it's extremely easy to use as is. For instance, you don't have to remember "the one way" to create a note, because there are five ways, which all do the exact same thing. (You can create a new note by either keystroke command, directly from within the Note tab in the NaviDoc, as a menu toolbar command, from an icon on the top toolbar, or from the icon toolbar on the right.)

Notes can be set up in 30 categories, each with their own unique color for background and text identifying them. These can be your personal notes, other people's comments, production notes, unresolved questions, and so on. They're listed clearly, and clicking on one will jump you to the appropriate passage in the script. (You can even print out all your notes separately. The option appears when the pop-up Print window appears.) And when you add a note into the screenplay, though the full text will be displayed on screen, it won't change the page length of the document. The program knows to overlook Notes when counting pages.

Finally, the Bookmark View is self-explanatory. You can create a list of bookmarks which jump you directly to their location in the script. On the surface, it's a great feature, though in reality, you can usually find what you want in a script just by doing a text search. However, there are times you just might not remember exactly the phrasing of a passage, so having a bookmark can save you. Also, though by default a bookmark will be created using the passage from the script where it's at, you can change the bookmark text to anything you want.

I have one quibble with a couple of odd inconsistencies in the NaviDoc. If you want to create a new bookmark, you use the key combination Ctrl-Alt-B. To create a new note, however, the combination is CTRL-SHIFT-N. (Ctrl-Alt-N would have been more consistent.) Also, while you can add a note directly from either of the two toolbars, for some reason there's no way to add a bookmark from a toolbar. None of this particularly is a problem, just odd - it's still very easy to add notes and bookmarks: just click on the Add Bookmark or Add Note icon in the NaviDoc.

Productivity tools

Movie Magic Screenwriter integrates smoothly with the other writing products its parent Write Bros. company makes, like its popular Dramatica and Storyview. And from within Screenwriter, it can generate an export file for Movie Magic Scheduling, an Industry standard tool for the production end. (While this is something production managers will appreciate, it's of course not a feature of particular interest for writing ...)

There are other production-based tools that are beneficial, however, should that be needed. (Or should you be a production manager.) Among them, you can color code revisions, as well as use revision marks, making changes easier to follow. (To remove all revision marks, simply select "Remove Current Revision Marks." Removing individual revision marks is easy, too - just put your cursor in the line with the revision and tap the "*" key. Simple though it is, you have to find this latter information in the User Guide. It would have been nice to perhaps reference it on the "warning" screen when selecting "Remove Current Revision Marks.") You can also create production breakdowns and tracking details from within the program. One feature, for instance, tagging, will find every instance of a specific prop and mark its scene and location.

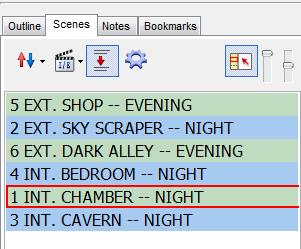

Movie Magic Screenwriter has a featured called iPartner, which allows for online collaboration. The program also let you assign different voices to characters, and your computer will "read back" your script, with its Text-to-Speech feature. (This is incredibly configurable, down to selecting a voice that whispers or echoes in a hallway. However, there's no default option to simply read the script without assigning anything, so it's a little more involved to use than just a click. Then again, as "cool" as this option may seem - and it's fun to test - I find it borderline pointless. Unless you plan to cast your movie with robots.)

This version 6 uses a different file extension than earlier versions. Now, the extension is .MMSW, rather than the previous .SCW. This makes zero difference in working with the program, but if you used an earlier version of the program, previous script files have to be converted. That's simple to do though: just use the Import menu option which will transfer your previous .SCW scripts into the new "Screenwriter Documents" folder. When it comes time to save the script, you'll only have one option, to "Save as..." Click OK, and it will be automatically converted.

Movie Magic Screenwriter can open script written in Word, Word Perfect and other formats, like the standard generic .RTF., though in some cases the formatting might be slightly off, and you'll have to clean anything that's off. (You cannot import scripts directly from Final Draft, but it's a simple conversion process: when a person is using Final Draft, they just click "Save As..." and select .RTF. It will be automatically converted, and can then be opened in Magic Screenwriter. This works the same way to get a script from Movie Magic Screenwriter into Final Draft.) This is one of the reasons why it's not critical to concern oneself with what program a particular TV show or movie production uses. It's not nearly as convenient as having the exact program, but you can go back and forth. MM Screenwriter even imports PDF files.

When you've done rewrites, the program lets you print out any scenes that have revisions. For that matter, there are numerous helpful printing options, including the ability to print out scenes with a specific character in them.

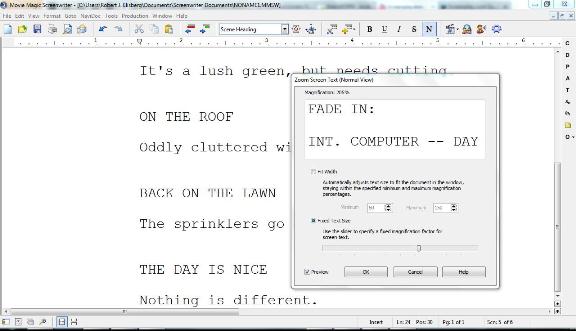

The earlier-mentioned Zoom Screen Text is a nice touch for people who want their script to look larger on screen and be more readable (or smaller to provide more material on their monitor), and doesn't change the pagination. There's a very convenient button at the bottom of the screen to pop up a box with a variety of zooming options, including a helpful preview.

While Movie Magic Screenwriter is very simple to use at its most basic - and easy, too, to explore and learn, there are nonetheless a great many features it's helpful to read up on, if you want to do some of the more intricate functions. The Manual is a PDF file that resides in the "Documentation" folder. It's very good, very comprehensive, and explains things extremely well. This information is accessible through the Help menu item, as well. However, good as the help information is, there are some inconsistencies. In one tutorial, for example, it shows a file to open as having the older .SCW extension, not the new .MMSW extension the program now uses. Or in the description of "Push Buttons" it describes five options in the enclosed graphic, but only four appear.

The company offers completely free, full tech support for the life of the product. This is not the case with Final Draft, which provides 20 free minutes of phone support for the first 90 days, but you must pay after that. (Final Draft does offer free, live online chat and email support.) MM Screenwriter has an extremely detailed FAQ section on their website, filled with a mass of information to answer most any question that may come up. I have one big quibble with it though: it's poorly organized, providing results for every word you use in your inquiry. If you ask, for instance "How do I" do something, it will bring up every question in its database that has the words "How" or "do" or "I" in it, rather than filtering results down to only all the words used. You'll find your answer, you just have to be diligent and patient in your search.

In addition, there are almost a dozen very helpful video tutorials on the Movie Magic Screenwriter website, under the Support/ Tutorials link.

The company has drastically improved its earlier draconian form of copy protection. You're still allowed just three installations, but now you control those yourself. If you've used your three installations, but want to add a fourth, a screen pops up and lets you "de-activate" a previous installation online and "activate" the new one. Since you can only write on one computer at a time - and because you can "de-activate/activate" endlessly, it essentially gives you the ability to install the program wherever and whenever you want.

There's also a menu option (under Tools) that lets you directly register your script online with the WGA. No need to go to the Guild's website or drive to the building.

Installation was fast and easy. But know that if you use the 64-bit version of Windows 7, a special driver must be installed first. It's extremely easy to do (just download the driver and double-click on it to install), but it was a bit hard to find this information in the FAQ, which provides that easy download link for the driver. If you use the more standard 32-bit version of Windows 7, however, this driver download is unnecessary.

In the end, for all the long and convoluted descriptions here, the core point about Movie Magic Screenwriter 6 is that pretty much everything about it is fast and easy. Equally impressive is how completely configurable the program is so that you can make it run the way you specifically want it to.

At the time of writing, Movie Magic Screenwriter 6 retails for $250, but was on sale for $200. They sell an Academic version for full-time students or teachers for $130. To upgrade from an earlier version of MMS, the retail price is $100, but on sale for $60.

FINAL DRAFT v8

The basic foundation for Final Draft is the TAB and ENTER key, though they're used a little differently than in Movie Magic Screenwriter. And though a great many of the bells-and-whistles overlap, as well, there are differences.

In Final Draft, the TAB key cycles through the Elements, generally going in order from Scene Heading to Action to Character Name to Transition, back to Scene Heading. (It acts slightly differently within Dialogue, toggling between dialogue and creating a parenthetical.) The ENTER key tends to go to the next logical Element.

It works easily and fine (how hard can it be to learn ENTER and TAB, after all?), though there are some propriety conditions. If you're writing a conversation between characters, for instance, and want to go from the end of dialogue to the next speaking character, you have to hit the ENTER key and then the TAB key, which gets you to the next Character Name margin. It's simple, obviously, though it's an extra keystroke compared to MM Screenwriter, which would be TAB only. This is very minor on the surface, though it can add up to perhaps 500-1,000 extra keystrokes over the course of a full screenplay.

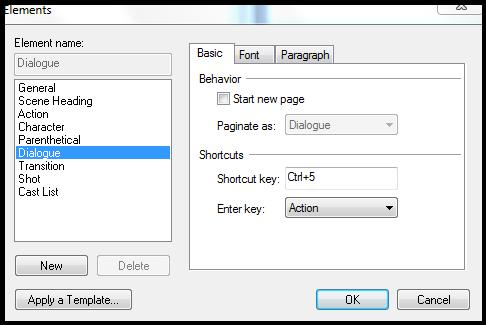

(You can configure the program to jump directly to a new Character Name, making the change under Format/Elements - remember, the program is highly configurable - but if you do override the program default here, you'll then have to use a keyboard "Shortcut" to replace the keystroke you just changed, like Ctrl-2, which isn't as elegant. More on Shortcuts later.)

When jumping to a new Character Name margin, the default of the program is to automatically "guess" and enter the previous character who's spoken. (It's displayed in light gray, and you press ENTER you accept it). This is a very nice touch and a keystroke saver, but know that it can be a little distracting if you have more than two people speaking in a scene - also, you have to be slightly more careful not to accidentally hit ENTER and insert the wrong character. Like most things in the program, you can change the default. And, of course, it's simple to override the "light gray" name that automatically shows up: you just start typing the name you want. The program's SmartType feature will pop up to display any name that starts with the first letters you type. SmartType also fills in locations and scene headings as you type the initial few letters.

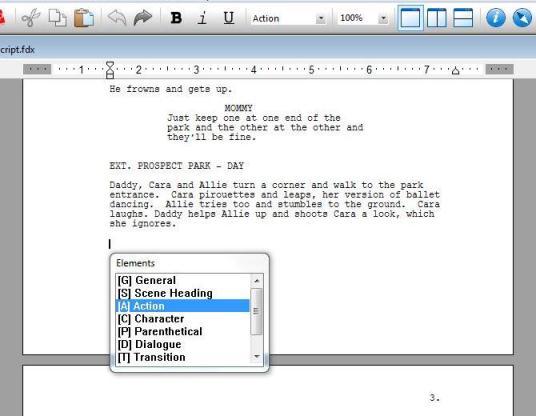

When you're at a blank margin (for instance, the start of an Action paragraph) and hit

ENTER, an "Elements Window" pops up giving you a choice of what Element you want to change to, like Scene Heading. It's convenient to be provided the choice, though it's unlikely that you'll usually want to do anything but start a new scene when hitting ENTER in a blank Action line (you're not going to add dialogue in an action paragraph), so this is extra keystrokes.

By the way, there are "cheat sheets" at the bottom of the screen, telling you what action a TAB or ENTER will do before using them. This is very helpful and keeps you from getting "lost." However, I found at least one inaccuracy, which the company said would be easy to fix.

And of course, as is one of the core features of screenwriting software, Final Draft does a fine soul-saving job of breaking pages and adding the appropriate "MORE" and "Continueds," and entering on the following page the character's name whose speech was broken on the previous page. And then instantly re-configuring all this should any text change. Additionally, it's easy to create title pages that get embedded before the beginning of your script file.

Note that when you save a script file, Final Draft doesn't automatically create a folder for it to be saved in for easy organization. Of course, it's simple to do on your own - though I know far too many people who haven't yet figured out how to do that and end up with an endless list of all their documents files run together.

Writing Tools

Final Draft is extremely customizable. Although Movie Magic Screenwriter allows you to change many more things about the full program, Final Draft lets you re-configure its toolbar to a much deeper extent, and that's where most writing commands reside. You not only can of course select the icons you want displayed, but can also change pretty much any keyboard command to how you prefer to type (also referred to as keystroke combinations, like Ctrl-N) - dozens of them, compared to just six in MMS. In addition, though only one toolbar exists by default (as opposed to MMS's three), you can create 10 toolbars in Final Draft, each one made up from any menu category. (For instance, if you select "Edit," then a new toolbar will be displayed that contains all the "Edit" menu commands. This new toolbar can then be dragged wherever you like.) It's quite easy - though also a bit more convoluted than ideal: not all the commands will display by default on a new toolbar, so you have to dig under the hood a bit to manually select the additional ones you want. But when it's done, you can have toolbars set up pretty much the exact way you want them.

The program also has two related features that simplify keyboard commands by automating them. One, the aforementioned Shortcuts, uses a Ctrl-key combination that jumps you directly to the appropriate Element. (For example, CTRL-3 moves your cursor to a new Character Name margin.) Macros, on the other hand, each start with CTRL-ALT and automatically enter slugline text, such as INT., EXT., NIGHT, SUNRISE. (Typing CTRL-ALT -4, for instance, enters the word "DAY."). There's no need to memorize this array of commands - a handy "cheat sheet" is provided at the bottom of the screen: whenever you hold down CTRL or CTRL-ALT, all available combinations are listed in full view for easy reference. Both are thoughtful features for people who like to use automated commands. The one thing though is that neither use intuitive or easy-to-type key combinations. Typing CTRL-ALT-D for Dialogue, after all, might have been a preferable combination than CTRL-5. However, the program reserves CTRL-ALT for text Macros only and is therefore unavailable for margin Shortcuts. Why that's odd is because jumping your cursor to a new Element margin would seem a more valuable function than entering text like "INT" - particularly because with the SmartType feature, these words can already be entered almost automatically. If you're not happy with the Macro keys, though, you can change them. But alas, not Shortcuts.

If you ever have trouble coming up with the names for characters, the program offers you some assistance: a Names Database that includes a whopping 90,000 names. This swamps the 30,000 entries in MM Screenwriter's Name Bank. However, in Final Draft, all names are lumped together in one mass list. MMS breaks the names down into male, female and surnames.

The Revision feature is extremely configurable, like most of Final Draft. Among other things, you can have revised text show in up to 10 different colors, which is good touch. To remove a revision, just know that you must highlight all the text in the revised passage (even text that wasn't revised), rather than just place the cursor anywhere within the text.

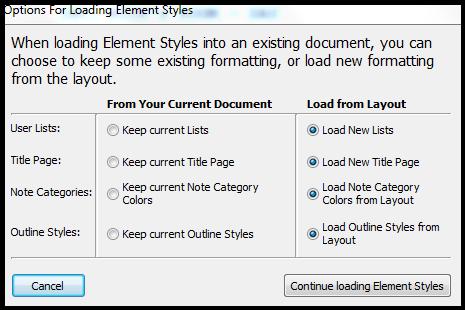

Final Draft does some interesting things with templates - some wonderful, a few less so. Templates are the "rules" that format how your script is laid out (like margins and how to break a page). The program includes a huge amount of pre-designed templates that you just load and can work from. This includes many screenplay formats, as well as in the hundreds of TV shows, stageplays and graphic novels. To load one, simply click File/ New from Stationary - and a pop-up window appears from which you browse through the list. In perhaps the most impressive touch, the program lets you easily stay current with additions of new templates by going to the Final Draft webpage and just downloading any updates from the Support page.

For all these positives, there are issues with how Final Draft uses templates - starting with a very minor point, calling them "stationary." Though deeply minor, it's an unnecessary confusion. After all, the company itself calls them "templates" on their webpage and in the "File/Save as..." box.

More problematic is handling new templates. While it's not something most people will try too often since it's a bit technical, writers do have their own personal formats they prefer, so it's certainly not uncommon. Under Format/Elements, a plain text window pops-ups with a few template options. By contrast, in MMS there's an elegant, graphical window full of clearly laid-out selections - along with a wonderfully designed Help button (whereby you can point your cursor anywhere in the window, and a pop-up explanation appears). This is important because changing template settings can be daunting. There's no Help button in the Final Draft "Format/Elements" window. Once you've created your new template in Final Draft, it's easy to save - just click File/Save as... and change "Type" in the drop box to "Final Draft Template." (As noted above, they do call it "template" here, which is why I suggested it might confuse some who now think of it as stationary.) In MMS, there's a clearly labeled "Save as Template" standalone button.

Related somewhat to templates are the tutorial scripts included with the program. These appear to be sample scripts with Final Draft features embedded, which is definitely informative though not overly tutorial. They're part of the Help system, which is good, though indicative of my biggest quibble with Final Draft. Happily, "help" isn't a feature you'll need all that much with Final Draft, particularly for the basics: the program is quite easy to use and reasonably intuitive. However, there are some small design issues that make "help" less user-friendly than ideal.

I want to be clear upfront: these are all quite minor. After all, Final Draft is an easy, well-designed program. Many people may even use it without ever coming across any of these glitches, or may ever even access any Help features. But together, these minor, individual issues relate to the recurring lapses I'm referencing.

For example, the Final Draft website has quite a few nice videos that guide you through many of the program's special features - like ScriptNotes and importing files. However, there's no video about Getting Started. (Or at least none that I came across.)

To load tutorials, you have to search for them in the Final Draft sub-folder under the "Program Files (x86)" folder - an odd location usually used for executable files, not where one looks for documents.

Additionally, Final Draft offer free, live online chat and email support, which is very good to have. However, they only provide 20 minutes of free phone support during the first 90 days after registration. Again, this is minor, but indicative of small oversights in user-friendly details.

For instance, there are a couple of notable mistakes concerning a core feature in Final Draft. On page 18 of the User Guide, it says that hitting ENTER will create new Action after dialogue. But page 30 contradicts this with "Press Enter to create a new character paragraph after dialogue." (The former is correct.) To be fair, most User Guides have mistakes (MMS has them, too), so this isn't remotely a big issue. However, this "dialogue" glitch is compounded by an error in the included "Swans of Brooklyn" tutorial script. When I spoke with the company, they acknowledged that when this tutorial was written some of the keystrokes in its template were changed and a replacement macro was used after dialogue. As a result, the tutorial doesn't utilize all of Final Draft's default keystrokes, which a new user wouldn't know.

To reiterate, all of these points are minor and may well come across as nit-picking, since the program itself works so easily and well, and a user may never require any of this. But two things must be noted: 1) in my years of writing about technology, I've learned that most people want you to tell them exactly how something precisely works, and any deviation can be bewildering. And 2) I'm comparing two excellent programs, so the standards are high.

And Final Draft does meet its high standards.

There is a very good dictionary and thesaurus, and you have the option to load dictionaries for numerous languages. The Text Magnifier will enlarge (or shrink) text on the screen, yet not affect your page count. And most notably, the program's Text Highlighter is an extremely nice feature that allows you to mark text as you would on paper with colored highlighters. (Finding the icon to add to your tool bar is a bit buried under Tools/Customize/Format.)

There's a particularly nice feature called Spotlight Search. If you have several different drafts of your script saved as individual files, Spotlight Search which will find any Version 8 file that contains your searched-for text. The search will not only look in the script text, but also the title page, ScriptNotes, and scene summaries. (Note that this feature only exists in the Mac version of Final Draft.)

Also, in regards to multiple drafts, Remember Workspace will conveniently open all drafts you were working on previously.

And if you work with a partner who can't be in the same location, the CollaboWriter®

feature lets Final Draft users write and even discuss their script together in real time over the Internet. Control of the script can be shifted between the writers, so that one person at a time is responsible for changes.

Panels System

Final Draft uses what it calls its "Panels System," which includes Index Cards and Scene View.

You're able to split your script page so that you can see your script in one panel, while looking at a breakdown of either your scene summaries or Index Cards in another panel at the same time. Double-clicking on any scene or Index Card jumps you directly to that scene in the script.

Final Draft adds an intriguing twist to the concept of Index Cards. It makes them "double-sided," allowing cards to have a Script View with the scene displayed on one side, while displaying a Summary View on the other side - where outline information or notes of any kind can be written and also "sent to script" (meaning it will add whatever is on your Index Card summary into the script). Unfortunately, Script View is view-only; only the first lines of your script is displayed, and you can't edit it. However, it's easy to toggle between these two Index Card views with just a convenient right-mouse click. (To switch between Index Cards and Scene View, though, you have to use the menu.) Index Cards in Final Draft can also be individually colored and rearranged easily if you want to reorder your script. And they can be printed directly onto 3x5 or 4x6 cards.

Though not officially part of the Panels System, several other Final Draft features work in a pop-up box way that separates themselves from the actual script and are worth including here.

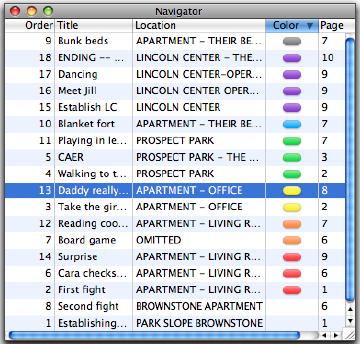

Most notable is the Scene Navigator, which lets you manage the important details of a scene in a "floating" window. This is a box that displays columns with the scene number, title, page number, and card color (if you've assigned one.) Clicking on any of these columns will sort the Navigator accordingly, giving you an overview of your script however you want to look at it. Click on any scene, and you jump to it in your script. Changing the order of scenes in the Navigator does not change their order in the script - it's to give you an easy way to organize looking at your material.

The Scene Navigator works in conjunction with another floating pop-up window, Scene Properties Inspector, which is where you can enter a title (like "Subplot introduced") and notes about a scene to track themes, characters and such, specific to any scene, and then color-code it. These all work well together with Panels, and give you good control over organizing your notes. The "floating" nature of the boxes can get a bit jumbled on screen, overlapping the Panel if it's running, though they're all easy enough to re-size and also toggle on and off if you have icons for the Navigator and Scene Properties on your toolbar.

Related to this are ScriptNotes, since they too appear in a pop-up window, and let you show or hide notes directly within the script. An icon appears embedded in the document where a ScriptNote has been placed. Click on it, and the note pops up. It works well, and notes can be printed in place or separately - but I have one issue with how the feature works. With a ScriptNote open, the moment you begin typing...the note hides itself. If you want to keep a note open while working on your script, it can't be done.

Productivity Tools

Though the bulk of interest in a screenwriting program is, of course, for the pure writing of the script, there are a number of bells-and-whistles that are perhaps more "after-the-fact" which are still be of interest.

ScriptCompare will compare two drafts of the same script and will highlight any differences between them.

If you've ever been concerned about a script being too many pages or too short - maybe for instance, a widowed line has spilled over to the next page - Final Draft has a feature that will adjust the line spacing of the entire script or even let you select individual sections of text, so that you can manage your page count. For some reason, this is called "Leading," but names aside, it works easily. (This only affects line spacing, not margins. However, it's simple to adjust the ruler to make margin changes for individual paragraphs.)

Text-to-Speech will "read" your script read back by assigning different voices to your characters. Unlike the similar feature in MMS, this can run without assigning anything, so it's much easier to use at its most basic level in Final Draft. However, I couldn't get it to change voice associations - every voice was the same, and it was particularly metallic and jumpy. Again, though, like MMS, it's a sort of cool but (to me) relatively pointless feature.

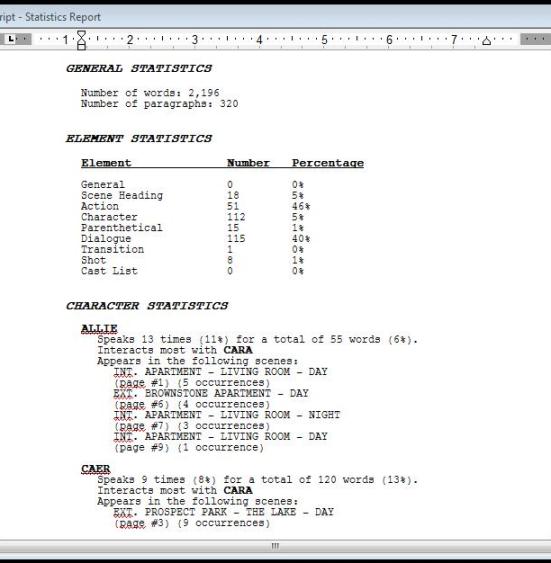

Numerous reports can be generated, like the Statistics Report which will break down into minute detail data about characters and scenes, including how often a character speaks (this is a godsend to actors - something writers might want to keep well-hidden...) and on what pages. Even the ratio of action to dialogue, if such a things matters to you - or a profanity report. You can also generate reports for individual characters, ScriptNotes, locations, or any Element in the script. This will mostly be of interest to production managers, property masters costume designers and such, though there are still benefits to writers.

In addition to printing your full script, you can choose what revisions to print or print selected views like the Scene View and Index Cards. As mentioned, you can print onto index cards, or print your script directly to PDF. Also, a one-touch command under the File menu will open an email and automatically attach you latest draft.

Like MMS, Final Draft lets you register your script through the Writers Guild West's online online registry service.

Though copy-protected, Final Draft can be installed on as many computers as you want. Two computers can be activated at any one time, but if you want to run the program on more than two computers, you simply deactivate one computer and then move the activation to another by using the command under the Help menu. Program installation was easy. To import Movie Magic Screenwriter files, those will have to be first saved as a standard .RTF format. It's simple to do, and this is the same as how MMS works. Although Final Draft can also import scripts written in other word processors, it requires a bit of a conversion process first.

For production purposes, Final Draft includes a separate program called Tagger, which breaks down a script into a shooting schedule for budgeting and prep. (Needless-to-say, this is of no use for writers, though of great benefit to production managers and ADs.) Among other capabilities, it will "tag" things like cast, costume and props that aid setting up production schedules. Because it outputs its data into any program that accepts XML, it makes for strong compatibility.

At the time of writing, Final Draft 8 sells for $250. To upgrade from an earlier version, the price is $100, but on sale for $80.

THE WRAP-UP

What's important to say upfront (if one can be "upfront" at the end) is how terrific both of these programs are. As stated at the beginning, you really can't go wrong with either. In some ways, the question isn't which is "better" - if one of the programs has a specific feature that is important to you because of how you prefer to work, that's likely the one to choose. If you work on a show where one of the programs is used, it's probably easier to use that program. If you write with a partner who already has a program, you'll have a smoother experience with the same one.

So, "better" is not necessarily the core question to ask. How you write and what's important to you is.

That said, as good as both programs are, I think that Movie Magic Screenwriter is a better-designed program. Its use of keystrokes is slightly more intuitive, there are several more user-friendly touches, and its creators seem obsessed with providing help. Bells-and-whistles are important, if you use them, and both programs provide strong features. But the core of any screenwriting program is - sitting down and typing. And I thought that Movie Magic Screenwriter handled the ease and range of that in a better way.

One thing I don't think should matter much when buying a screenwriting program is cost, if you're getting it for professional purposes. The prices are close enough and both have periodic sales so that, when it comes to what is the most important tool in the writing process, it's far better to use what works for you the way you like to write.

(If you're not a professional, and hoping to get into screenwriting or have that great idea you need to write, then price does come into play. And there are other options out there. One, for instance is called Celtx, which can be downloaded from its website for free. I haven't tested it, so I can't offer an opinion. Keep in mind, if you're just going to create PDF files or print scripts out, compatibility is not a critical issue. It may work wonderfully or not, but if you don't like the program - hey, it's free.)

As I said, too, at the beginning, people who use one of these programs or the other will insist that theirs is the absolute best. They will say this for innumerable reasons. It's rare, however, that they will have actually used both, to make a fair comparison. And so, I will repeat (yet again): both Movie Magic Screenwriter and Final Draft are wonderful programs. Both are widely used in the film and TV Industry. If a feature exists in either that is critically important for you, that's the one to look at first. On a blank slate, though, I thought that Movie Magic Screenwriter offered more core benefits.