The anxiety of the poet in the information age is to have one's work reduced to that cheapest of technological commodities -- "user-generated content."

You may not yet have heard of Tim Krcmarik (US) or David Clarke (UK), but to me their debut collections represent some of the most interesting poetry being written today. Furthermore, their books serve as fine examples of how poetry grapples with the problems of the information age, and each illustrates how tactics can differ on their respective sides of the Atlantic.

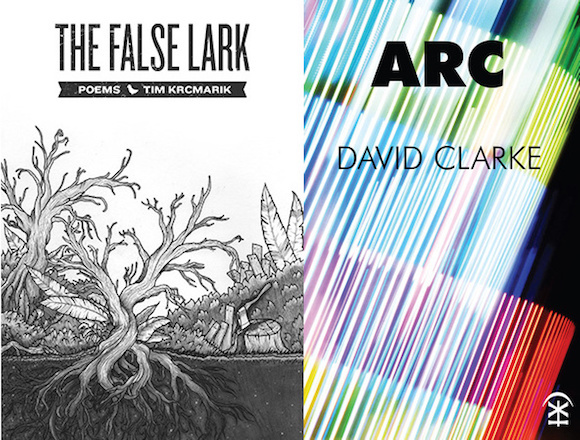

The False Lark (Diabolical Genius Press, 2013) by Tim Krcmarik is an convincing debut, deploying syntax assuredly to great effect. If you cover up part of any poem, there is no way to guess what is coming from the previous lines. The element of surprise is always Tim's. Yet the pieces cohere, and touch on matters essentially human, and existentially grand, in the midst of so much singular nuttiness. It's big band with heart, and it is utterly fresh.

As a fireman in the city of Austin, Texas, Krcmarik finds himself, "composing on the back of a utility bill / long past due." As a poet in the twenty-first century, his labours are self-conscious, grappling with individual meaning amidst the drone of the twenty-four hour news cycle not unlike another recurrent figure in his poems -- Sisyphus.

Indeed, who better than he to symbolise what Billy Colins called the ridiculous gulf between "how seriously we [poets] take ourselves and how generally we are ignored by everybody else"? Sisyphus is the modern poet's mascot, reimagined by Tim in the poem "April" as that "old fool toiling" alongside an upper-middle-class family in an SUV commercial whose members "point and jeer" at his labours, "his long green beard / mobbed with songbirds and flower blossoms, / trailing for miles behind him."

Part and parcel of this self-consciousness for both Krcmarik and Clarke is a capacious, magpie-like affinity for combining classical and pop references, modulating diction from high to low, and bounding in a single line from the mundane to the deeply philosophical.

One of my favourite examples in The False Lark comes early, in the poem "Zombies," where the speaker is roused from a suitably Romantic half-dream state by his lover's question, "If my soul / were an object, what would it be?" From the "dark field of unconsciousness," "Braaains, suggests a zombie. Braaains, // another echoes, its ragged jawbone / clattering to the ground." Yet the speaker rejects "chemical causation" and "a wind of neural phantoms," preferring to "sit here in the starlit grass // gazing upon the wondrous moon of your face." He instead consults a philosophical alter-ego, the butterfly, "wings fluttering the way your eyes do / when you dream you're falling / and discover flight."

The poem achieves liftoff through a chemical reaction between deep ontological questioning, b-movie horror imagery, Darwinian musing, and the rapid eye movements of a lucid dream. In an age when a single search term can pull up a tremendous archive of ancient Greek philosophy alongside an equally vast archive of pornography, Krcmarik has learned to harness the power of the profoundly eclectic to his artistic advantage.

Yet these poems are far more than one man's romp through associations, but are placed in the context of disillusionment and anxiety, including toward the promises of America's darling, capitalism. In "Hard Candy" he compares his lover's breasts to "A military industrial complex / of cherries jubilee!" and in "Money" he regards "the little top-hatted Monopoly guy / waxing his moustache next to me" as "an unwanted houseguest."

These are poems that also work hard to reclaim language from the psychological-industrial complex of consumer marketing. Above all, they take for their materials the quotidian and make of them, through quirk, dry wit, and bounding leaps, something new, like his admired "Cat," "hissing your cantankerous / feline haiku / at nothing in particular, / the very thing / you love most in this world, / nothing in particular."

Indeed for Tim, like that other symbol of the contemporary poet, the ordinary tulip, "your long hours of death and failure / have been worth it, / the ignoble self-pity, the bog of self-doubt" for these are poems deserving -- if not of "ten million kroner and a gold medal" -- at least sincere appreciation from this attentive reader for a linguistic boldness that is truly invigorating.

If much of American poetry is a declaration of independence, much British poetry is about tending the bruise of history.

David Clarke's Arc (Nine Arches Press, 2015) regards American icons, for example telling Superman, "I feel like every shiver / in the air could be your passing. Asses / still need whipping and you're such a giver -- / giving them hell, I mean." Like Krcmarik, Clarke tilts a line's meaning a full 180 degrees through masterful syntax, modulating between high and low diction effortlessly.

Yet Clarke's view of America, with a melancholy and ever-departing Jimmy Stewart, is from the distance of an England brimming with past disappointment, thoroughly modern "Epic Fails," and the weight of European history. The excellent "than you expected" is a well-ordered list of all the elements of a life that can turn out more, less, or different than what we would have wanted.

Loss haunts these poems. In the gorgeous "Driving Back to Lincolnshire for a Funeral" the lush dark imagery is redolent of a second-world-war-era past, the "pillbox hats" and "blokes in caps" receded to "its straggle of Forties / council houses, the then des-res homes / packed tight against that winter's useless moan." Returning to the journey's purpose, the speaker, "stepped into the rain-whipped dark and hollered -- / 'just give me some years when no-one at all will die!'"

These poems are also tinged with a different kind of poetic self-consciousness, that of "queerness." In "Exodus," set at a gay pride festival in London, the speaker and his companions "lounged in glare like exiles thrown / on a luminous shore." The word "Queer" itself, scrawled on the boys' bathroom wall next to the speaker's name, underscores the memory of "that cavernous afternoon" with "wafts of disinfectant and playing fields."

The book also gathers up classical references alongside popular culture, from the more obscure "Asklepieion of Epidauros" to Achilles as a dashing barman with a shaved chest. Yet amidst the tussle with identity and philosophy is a more recent socio-political context as well.

Clarke's disenchantment is with communism, deriding the "reactionary" sentimentality of "Lenin at the Music Hall" and sneering at deeply hypocritical "optimism" in "Notes Toward a Definition of the Revolution." The poem "How it Was" reveals a bleak Soviet reality coupling, "The necessary lies. / The unavoidable truth" and "Blood in the mouth. / Song in the head."

Still, it is ultimately the hypocrisy of Western mass-marketing, and that mass-marketing of public policy known as politics, that Clarke seeks to upend, the "Permanent Emergency" of the post-Blair-era with its "lobbying for 'hearts and minds'" while Clarke the poet-outsider goes about the business of singing out his "post-traumatic pastoral."

A fine example of the decidedly British way in which Clarke's equally voracious turn of mind reclaims language is in "See England by Train." The poem peels away the gloss of tourism brochures, giving us instead what one really sees alongside the tracks -- "the doubtful / pomp of orange plastic netting, / pearls of polystyrene tussled in briar." Yet the poem gathers up these sad elements in its arms, and lifts them in a Blakean oration along with, "England's sons cowering // beneath the ancient shrug of iron bridges ... Its daughters also, straddling abandoned / lengths of concrete pipe, their laughter / blown back upon them like smoke / in muzzy rain."

Daring, deft and full of restrained verve, "Sword-Swallowing for Beginners" could have made an equally good title for this gripping and gifted book.

Each poet takes on the "cabbages and kings" of always-on smartphone-fed modern living with some age-old poetic tactics -- deploying idiom and imagery, working over the expectations of grammar and enjambment, tuning the music of language into an art that transcends technobabble, and reaches -- self-consciously, like a troubled adolescent -- after the sublime.