A well-functioning community college is one of the best ways to help students succeed by providing access to degrees and technical credentials that are crucial in today's economy. But right now, California's community colleges are burdened by an only-in-California decision-making structure that thwarts rather than values leadership. Here I offer another story about how this broken decision-making structure is undermining higher education in California, and how the problem can be fixed.

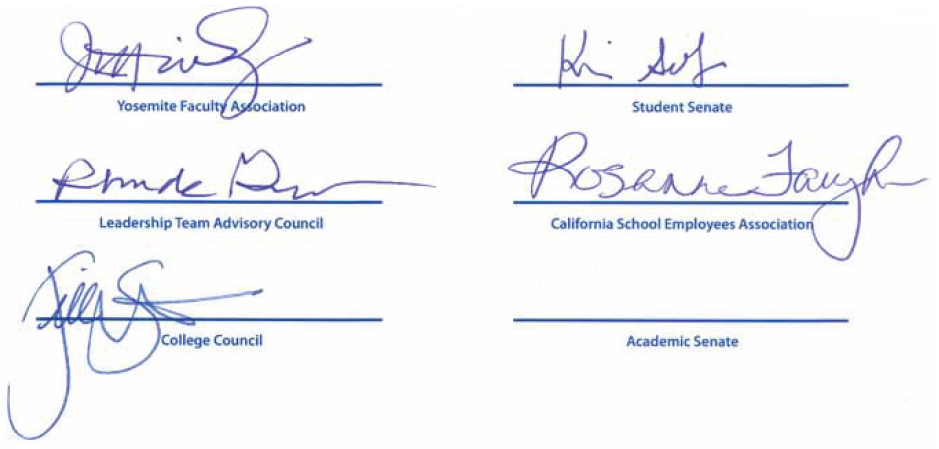

The signature page of the new governance handbook at Modesto Junior College tells the whole story. Engaging All Voices, which lays out a process for ensuring broad input into major policy decisions at the college, is signed by the student government representative; it is signed by the staff council and by the heads of two other advisory groups; it is even endorsed by the faculty union. The conspicuously blank space belongs to the college's academic senate.

Chancellor Joan Smith and the other stakeholder groups bent over backwards to accommodate the disproportionate demands of the academic senate, so much so that the other groups were "very unhappy" because they "felt they were not given equal opportunity to provide input." But because 100 percent of their demands were not met, the senators are refusing to recognize the decision-making manual as legitimate.

The chancellor, seeking consensus, was left with no good options. Cave to the academic senate's demands and risk upsetting other faculty leaders, students, staff and administrators. Prolong negotiations in an attempt to reach a consensus and divert precious resources from serving students, with no guarantee that the academic senate would ever try to reach agreement. What's a chancellor to do?

Chancellor Smith took the third bad option: move ahead without academic senate support. Clearly exasperated, she explains that the college must move forward or risk fiscal collapse, the loss of accreditation, or both. By asserting its veto power, the academic senate, like its El Camino College counterpart, can now question the legitimacy of any and every decision that is made using the new process, jeopardizing the very existence of the college.

Anywhere else in the country the academic senate's obstinacy could be written off as absurd. But in California, community college academic senates claim special powers: regulations severely restrict the situations under which they don't get their way. The idea behind the rule was worthwhile: to make sure that faculty members are an integral part of managing and improving the college. However, giving a faculty committee equal decision-making status with the governing board has in too many cases contributed to hostage situations like in Modesto.

The agency responsible for these misguided requirements recently denied our request for revisions that would eliminate the veto while still requiring consultation. While acknowledging that the regulations give an academic senate the ability to "inhibit action," the agency's letter insists that "there is no veto power involved" because the regulations "provide mechanisms under which local boards of trustees can take action contrary to the recommendation of the academic senate."

What are these mechanisms? The letter doesn't explain, but the regulations say that in the case of a disagreement with the academic senate:

"existing policy shall remain in effect unless continuing with such policy exposes the district to legal liability or causes substantial fiscal hardship. In cases where there is no existing policy, or in cases where the exposure to legal liability or substantial fiscal hardship requires existing policy to be changed, the governing board may act, after a good faith effort to reach agreement, only for compelling legal, fiscal, or organizational reasons."

In other words, moving forward without formal, written senate concurrence requires clearing a hurdle demanding legal interpretations of any number of vague terms, as well as consideration of metaphysical questions about the existence of a policy.

Veto. Inhibit. Filibuster. Whatever the right term, the Modesto situation is a clear and present example of how the state rules mire California community colleges in a swamp of ambiguity about how decisions are supposed to be made. Legally the safest route for a college is inaction, which perhaps explains why so many California community colleges wait for the crisis to occur and then frantically scramble to repair the damage.

The letter from the state regulatory agency says that our diagnosis of the problem is wrong. When academic senates wield their authority unreasonably, the agency says, it is merely a symptom of deeper problems such as poor leadership or union issues. Judging by the signatures, it doesn't look to me like the agency's dismissive diagnosis fits Modesto Junior College.