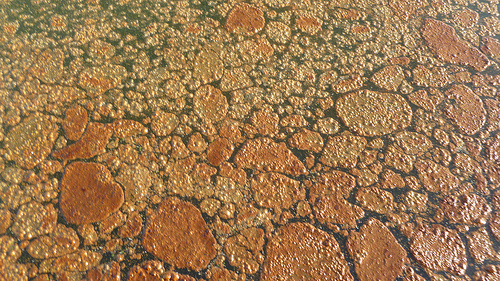

The pictures below were all recently taken on July 28, 2010, just off the Gulf coast of Grand Bayou near Barataria Bay. They were taken shortly after cleanup authorities announced major surface oil had been cleaned up.

Yesterday, Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal announced commercial fishing has been reopened in some areas of the bayou. The governor called this a "positive step" and called for more testing "so commercial fishermen across our coast can get back in the water."

You would think this kind of news would have people like Clint Guidry, president of the Louisiana Shrimp Association, dancing in the aisles.

But he's not.

In fact, he's downright discouraged about it. The way he figures, BP and the myriad of state and federal agencies monitoring this historic mess need to slow down and do more testing. They need to make damn sure the oil is gone before they allow shrimp boats to drag their nets along the muddy bottom of the Mississippi delta, stirring up huge swaths of chemical dispersant-laden oil that lies under surface of the Gulf and the bayou. If that happens, Guidry and most fishermen around here know all it will take is for one oily contaminated batch of shrimp to make it to market and end their season -- and perhaps their careers.

Why are Guidry and everyone else worried? In a word: dispersants, the magical chemical concoction that BP has been spraying madly everywhere for the past three months. According to BP cleanup workers and local residents, they're still spraying, even spraying close to shore at night.

"They're burying it," Guidry says. "That amount of oil doesn't just disappear overnight. It's got to be somewhere. If they haven't captured it on the surface or on the shorelines, then it's got to be on the bottom. And that's the last place you want it to be if you're a shrimp boat fisherman."

Guidry and many other fishermen I've talked to agree that BP's intent all along has been to bury the oil underwater and keep it out of sight. Some biologists agree that keeping it underwater and out of the marshes is best. But many fishermen think once it gets on the bottom, it can't be retrieved or cleaned up. It's stuck in the muck. And if it gets stirred up by boat or by storm, it will not be a pretty picture.

Dean Blanchard is president of Blanchard's Seafood, the largest shrimp distributor in the state. He's worried too. He's seen and heard dispersant planes flying around nearby Barataria Bay, one of the hardest hit areas by the oil. "They're just sinking it," Blanchard says. "It's not being cleaned up." BP denies it's applying dispersants close to shore. But that's not true according to residents in Grand Isle, who were attending a town hall meeting there last night. They've seen them and heard them flying nearby, especially at night when the cleanup crews come in.

Several fishermen involved in BP's cleanup operation have told me that crews who've spotted oil on the water and have tried to skim it up but were waived off by BP and told to evacuate the area. They say BP then flew in dispersant planes to spray it so it sank.

"They're just trying to hide it," said one cleanup worker. "Then they'll leave us with nothing to fish."

The people who sell shrimp are worried too. "I don't know what I would do," says Karen Hopkins, who works at Blanchard Seafood, which normally sells 13-15 million pounds of shrimp a year. "After all the dispersants they've been using around here, I don't trust anyone right now to tell me it's safe."

Trust. That's a feeling severely lacking in the fishing community here. No one trusts anyone after three months of anxiety and depression, watching wave and wave of oil pour into their fishing grounds. They don't trust BP, the Louisiana fish and wildlife agencies, the EPA or virtually every politician who parades through these communities with false promises and grandstanding accusations. They've seen it before during Katrina. Now they're seeing it again. Some people who are connected are making good money off the misfortune of others. Most are just trying to get by.

Two days ago, I took a late afternoon boat ride with Eric Tiser, a member of the Houma Tribe and a fisherman who was born and raised in Venice. Tiser has never been hired by BP to do cleanup work, although he knows the bayou like the back of his hand. He says many of his friends haven't gotten any work either. But plenty of out-of-towners with political connections have, some of them getting hired on with three or four boats a piece. That's $2,500 a day for captains and $1,200 a day for deckhands. Not a bad wage around here -- or anywhere. But some fishermen like Tiser haven't seen a day of work for BP.

Tiser took me out through the labyrinth of canals that crisscross the Louisiana delta and out to Barataria Bay and to the Gulf. We rode in a small skiff along the seashore. The beach was deserted, but there was evidence of cleanup workers everywhere; bags, boom and ever port-a-potties along stretches of beach that were inaccessible to the public.

As we cruised along we came upon sheens of oil, patches of red, crusty orange globs of crude mixed with dispersants that looked like spongy orange cake batter floating in the saltwater. Some patches were milky white, the color of dispersants, and some bright orange. Some areas were green, where it appeared droplets of oil stretched down to the murky bottom. The smell was overpowering, like being stuck in a gas station with all the pump nozzles pointing at your face. It gave you a headache just being there. I had one the next day.

But probably the most disturbing thing was the sea life, or lack of it. We would see occasional fish dart around in the water, some of them doing circles at the surface before dropping to the bottom in a death spiral. A few pelicans flew by, and some porpoise swam in the cleaner patches of water. But the sea life was not abundant, and it seemed more like the Dead Sea than the most vibrant fishing ground in the world. Along the shore, oil was everywhere. Tiser sank into the mud and pulled out an oil-soaked foot that had become stuck in a glob of petroleum-tainted marshland mud.

"This is cleaned up?" Tiser asked. "They've sunk most of the oil. They don't want to clean it up. They want to bury it and leave it here for us."

Seeing this oil -- some of the worst I've seen in many boat trips here since early May -- was very sad to see. But what is more discouraging is the story line now being promoted by BP -- and in the press. The oil spill is over, the dangers have been hyped. And look... even the marshes are coming back!

Well, I'm sorry to report that the fishermen I've come to know well and to trust, tough men and women who have survived horrific storms most Americans will never see, have a different story to tell. This disaster is not over, they say. It's just beginning.