"Are you hungry? Did you sleep last night? Are you taken care of financially? What do you need from us? What can we do to help?"

These are critical questions to ask a high school student who walks into your class sleep-deprived, because he had no food, heat, or hot water last night, because his mother used her welfare check and sold her food stamps to buy crack cocaine, and hasn't been back home in the last few days. Aside from the fact that he hasn't received proper trauma counseling from the loss of one of his friends to gang violence, this student has to prepare for his upcoming final exams, which will determine whether or not he is eligible to move on to the next grade (assuming he even cares).

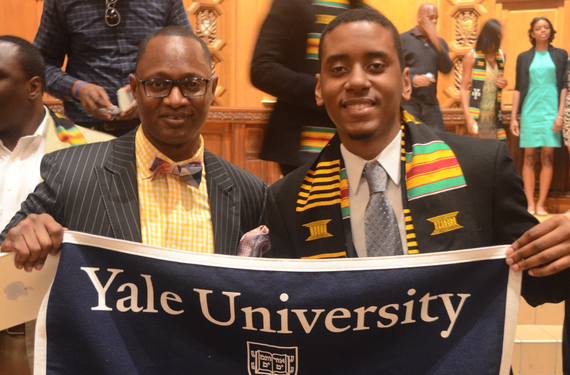

In my new book, A New Day One: Trauma, Grace, and a Young Man's Journey from Foster Care to Yale, I aim to help readers understand what it practically means to mentor at-risk youth dealing with extreme adversity in their day-to-day life experiences. I emphasize the ways that educators can position themselves to critically engage students, help them reconcile with their traumatic life experiences, and re-direct their energy and focus on ending the cycle of poverty and social failure, thereby chartering a new path to success.

By my senior year of high school, I had already gone through a whirlwind of life-shattering circumstances. I had spent thirteen years in the foster care system, within 12 different homes, and experienced physical, psychological, and emotional abuse from caretakers. I had struggled academically up into my early years of high school, which put me at a disadvantage for college acceptance. After emancipation, I was living with my parents, who struggled excessively with drug abuse and socio-emotional trauma. Lastly, I had no sense of guidance or direction as to what I wanted to do or who I wanted to be.

Conventionally, it's not a teacher's job to dig deeper into the deprived conditions of the students they serve. Teachers (non-tenured) are evaluated based on their students' standardized test scores and their ability to teach the required material; two metrics that don't deal with the systemic elements that cause deficiency in student performance. Students who have social and emotional trauma that goes unaddressed are likely to suffer from mental illness, and will succumb to poverty, social failure, and violence.

Thankfully, I met educators and mentors who thought enough of me to sacrifice their time, energy, and resources to attend to the trauma that stifled my growth at an early age. I met leaders who cared more about if I was safe than if I had studied. I had teachers who gave me their personal time before giving me their tests. I had mentors who treated me like a son before they treated me like a student.

Some people call this "radical mentorship", but we must be willing to do what's necessary to help students who are at a severe disadvantage. For many of us, we need mentors who will be able and willing to take us in and get us out of our violent, destructive homes and environments. We need mentors who will help us with structure and support (i.e. critical counseling, rehabilitation, relationship building, discipline, etiquette, college applications and job training). Most importantly, we need mentors who will help reorient us to a different way of thinking and being. Relevant education, combined with exposure (i.e. college tours, trips to different cities, international travel, etc.) will open up our minds to the great possibilities available in the world. All of this will require adult mentors to reclaim leadership in our communities.

What does mentorship look like for 21st century at-risk youth? It doesn't look like the conventional methods of mentorship. It is giving several hours each day to a few, versus one hour on some days to many. It is seeing to it that when they come to school, they are in a place and space to learn. It is when you can develop that deep bond and trust through time spent and critical engagement. It looks like passion and not obligation. Mentorship is not simply about playing a role, it's about being the answer to a young person's plea for help, whether by verbal or non-verbal communication. We are dealing with at-risk youth living under the most extreme life-shattering circumstances and it is going to take the same extreme, life-altering mentorship to redirect their future.