The other evening I received a Facebook message from a student who had been in my freshman social studies class in 1992: "Can I buy you dinner one of these days so you can explain this extremely complicated election process to me? I'm sorry if that means I wasn't an ideal student twenty-plus years ago when you tried to teach me this stuff the first time."

My mother, who has been voting since 1968, calls regularly to ask election-related questions. After a long conversation about politics yesterday afternoon, she summed up the conversation thusly: "This is a very confusing way to elect a president!"

My former student and my mother are hardly alone in feeling lost. Many (most?) Americans are hard pressed to explain the difference between a caucus and a primary; between an open and closed primary; between a winner-take-all and a proportional delegate split; between a delegate and a super delegate; between an open or contested or brokered convention; and between a popular and an electoral vote.

The process is labyrinthine and dreadfully confusing. But must it be? Can we simplify this great quadrennial civic exercise? Make it more straightforward and citizen-friendly? I believe it's possible to do so -- before 2020. Here are a few reforms worth considering:

- Caucuses are puzzling and chaotic. They consume a lot of time. By design, they eliminate the private ballot. And the viability threshold expunges the voices of those who support minority candidates. I'm not sure even I -- a teacher of government -- would participate in the mayhem of a caucus night. If our dozen caucus states opted next time around for an open primary system, like most of our states already have, it would place all citizens and all states on equal footing.

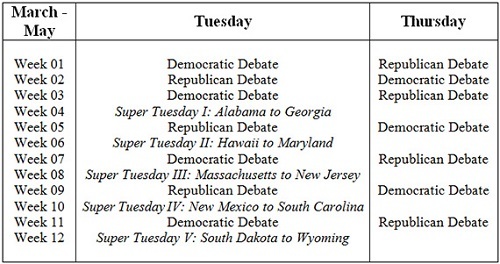

- Speaking of debates, is there anything we can do to tone down the raucous affairs they have become? Debates should provide in-depth opportunities for candidates to engage in thoughtful, fact- and data-driven conversations about the social, economic, and foreign policy challenges facing the nation. Too often they do not. At the very least, can we eliminate the WWF-style cheering and jeering of ginned up audiences?

The American presidency is the most powerful office in the world. The president has the authority to launch a nuclear strike. How we choose that person should be a careful, thoughtful, and forthright process. Right now, it is not -- just ask my former student, my mother, and millions of other citizens. Over the next four years we have an opportunity to do our country a great favor by making the 2020 race an exemplar of consistency, transparency, and democratic simplicity.

Rodney Wilson teaches American political systems at a community college in Missouri.