Enrique Peña Nieto's presidency is now at the halfway point, but there is no consensus on whether his first three years in office have provided the blueprint for the country's economic transformation, or set the stage for yet another disappointing sexenio. On one hand, it is a government that fulfilled its campaign promise of passing a structural reform agenda, one which could represent the country's most important reinvention since NAFTA. On the other hand, economic performance during the term has been less than stellar, and the slump in oil prices has the potential for becoming a major headwind over the next three years.

The political front has also been a mixed picture. By far the government's crowning achievement was the Pacto por México, in which all three of the main parties agreed to push forward the main reforms. Rarely had such a spirit of consensus existed in Mexico's short democratic history. However, Peña Nieto's honeymoon period came crashing down dramatically due to the administration's gross mishandling of the 2014 Ayotzinapa kidnappings and the subsequent conflict of interest scandals that directly implicated the president and his inner circle.

Since then, views on Peña Nieto's presidency have become much more critical, which in turn has paved the way for a more honest appraisal of his performance compared to the flattery bestowed in his first two years (particularly by the foreign press). The question is now whether Peña Nieto's legacy will be that of the great economic reformist, who placed Mexico's economy on the path to growth despite an adverse global environment, or the anti-Democrat who weakened Mexico's already shaky rule of law foundations and perpetrated the vices that have plagued Mexico's political establishment for decades.

The problem of the rule of law

It is on the rule of law front that the Peña Nieto administration has left so much to be desired. Part of this has been the sheer amount of political scandals that have broken so far in the term, of which the infamous 'White House' affair of 2014 deserves special mention for being the first since the 1970s which directly involves a sitting Mexican president. Beyond the scandals, however, Mexico has shown little if any advances in terms of its institutional development by all measurable accounts, be it corruption perception, freedom of the press, or democratic freedom among others.

However, to ascribe Mexico's institutional deficiencies to Peña Nieto and the PRI is unfair. At worst his government can be blamed for easing back into a system that it helped create after 70 years of power, one which the PAN was all too comfortable fitting into rather than challenging during its two terms in office in 2000-12. Few voted for Mr Peña Nieto in 2012 under the expectation that he and his party were going to launch a rule of law revolution and if anything, voters were quite happy to accept the likelihood of persistent corruption, impunity and patronage (which were widespread already) if at least it came with some degree of policymaking effectiveness - which was sorely lacking during the Fox and Calderón administrations but which the PRI at one point in its history did well.

Although the voices of the anti-PRI crowd ring strongest these days, it is clear that voters have punished the political establishment equally, as evidenced by the PRD's dismal showing in the mid-term elections, which also saw the PAN obtaining disappointing results. In that sense, voters are indeed correct in believing that Mexico's rule of law issues transcend party lines and are reflective of a political culture that has changed little over time with regards to its unacceptable tolerance of wrongdoing. This lends credence to view that recent anti-corruption efforts (such as the so-called Anti-Corruption System passed with near unanimity in February) will only pay lip service to addressing the problem in the years ahead. Expecting Mexico's politicians to discipline themselves is a tall order.

Yet at some point, increasing demands by civil society for greater accountability from the country's elected officials will have to be translated into outcomes rather than just rhetoric. Unfortunately, the government's dismissive attitude towards its critics further suggest that it is unlikely to be particularly concerned about corruption insofar as it does not affect its political survival (which only briefly during the mass protests of late 2014 appeared in question).

Can the reforms still be the Peña Nieto legacy?

The most pressing economic prerogative over the next three years will be to ensure that the reforms deliver on their stated aims. The good news is that some of them have begun to show promise: the telecoms reform has already seen a marked reduction of prices and the entry of new competitors into Mexico's tightly controlled telephony market; the banking reform is likely to be at least partly behind a recent increase in credit growth (now in double digits); and the fiscal reform has had a better than expected effect at raising tax intake -- and which in turn has helped make up for some of the lost oil revenue. The jewel in the reform crown, the energy reform, is still in its early stages but a successful second phase of tenders in September has made up for a less appealing first phase earlier in the year. Next year, the domestic electricity market will begin to open to competition and it is widely expected that this will help bring down electricity costs for households and businesses.

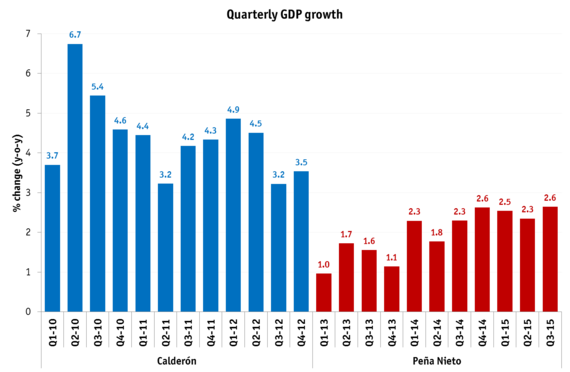

However, the reforms come against a backdrop a chronically weak economy and the collapse of global oil prices, which has hit crude exporting countries like Mexico quite hard (typically around one-third of the budget has depended on oil-related revenues). There is little that the government can do about this, as the economy's dependency on oil - mostly on the fiscal side, less so on trade - has been a drag since the 1980s. The risk, therefore, is that the reforms will end up simply plugging the gap from structurally weakened growth prospects into the medium-term. At one time, it was expected that the reforms could add as much as 2 percentage points to GDP growth, bringing Mexico's potential growth rate to around 5% in the medium term. Few expect anything near this nowadays.

This situation highlights what has been the administration's foremost economic policymaking failure: the belief that passing the structural reforms was all that would be needed to unlock Mexico's economic potential and that all other problems would naturally sort themselves out. Perhaps this explains why the government - in particular the finance ministry - was so passive in the face of a slowdown that began as soon as it took office and only entered panic mode once the threat of falling oil revenue became evident late last year. It may also be the reason why efforts on the socio-economic front have fizzled out: in fact, 2 million Mexicans have been added to the ranks of the poor between 2012 and 2014 according to the government's own statistics. There no Plan B to prop up short term growth, nor is there a convincing long-term vision of how to improve productivity (a concept that does not appear to be fully clear to the country's economic policymakers) and get Mexico out of the middle-income trap where it's been languishing for almost four decades. At some point the government must recognize that the structural reforms are a necessary but insufficient recipe for progress.

Looking towards 2018

As such, the Peña Nieto at its mid-way point leaves a country only a small step closer to finding a path towards prosperity, but possibly a big step back in institutional development. Mexicans would possibly be willing to tolerate less of the latter if the economy was delivering on its promises. But in the absence of measurable and immediate economic results, the administration's political shortcomings (exacerbated by Peña Nieto's unconvincing efforts to correct his numerous blunders) will become an ever growing liability with important consequences for the 2018 presidential race. This will be not just for the PRI but for all of Mexico's traditional parties and upstart independents, which will be under pressure to demonstrate their willingness to revamp a political establishment that looks increasingly ill-suited to carry the country into modernity.

Follow the author @raguileramx