I truly believe that the exhibition Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art, which is currently on show at the British Museum, is not only spectacular, but also very necessary. In times of the selfie, Grindr and Instagram, when our relationship with our body has become a source of self-punishment, consumption and shame, this show creates a mirror where to look at to see the good and the bad in us. From those who try to run away by obsessively running marathons to those who can only find a social life in rubbing their muscular bodies against other ones exactly like theirs, our time seems to be one in which the body is more used to cover (and, of course, magnify, our own insecurities) than to disclose.

This is why, I was not only interested in the exhibition itself, but also in the way the critics have interpreted. The first critic that I read was The Guardian's post-Victorian, chauvinist-like Jonathan Jones, who could only find fascination in the fact that such a "collage" of works had been secured by the "British Empire." Far more interestingly and, potentially, intelligently, The Evening Standard's Brian Sewell perceived (and, in my opinion, exaggerated) the erotic component of this show. In his own words:

I am inclined to believe that the Ancient Greeks were well aware of the erotic charge in sculpture. It is clearly demonstrated by the myth of Pygmalion, a kingly sculptor who fell in love with the ivory figure of a girl that he had carved, and reinforced by the record of the cult statue of Aphrodite at Knidos (Turkey), which proved to be of such stimulating beauty that her marble buttocks always bore the stains of semen.

Sculptors could hardly reduce the attractions of the female body, but the genitals of the male were easily reduced to inconspicuousness. They could not be omitted but they could be denied significance; given the genitals of a pre-pubescent boy, the magnificent Riasce bronzes are to be admired primarily for their dramatic heads and musculature.

And then carries on by saying:

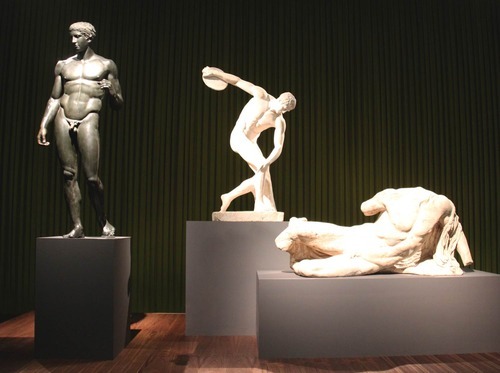

There was, I presume, no erotic charge for the viewer or the sculptor of the earlier Greek sculptures of the standing male nude, the kouros, made six, seven and even eight centuries B.C. -- archaic is the word for them. Hieratic, they are simplified to broad shoulders, slim waists and prominent buttocks; Egyptian influence plays a part, Mesopotamian too.

So, according to Brian Sewell, eroticism is directly linked to naturalism. What about the link between presence and love? These were images that did not represent a person or deity, but presented it before them. They conjure them and made them appear in the same way that we believe that a polychromed sculpture actually is the Virgin Mary when we go to church. Perhaps that is why we might actually dare to kiss her and touch her. It is not just arousal, but love.

The truth is that the body in Ancient Greece was the expression of an ideal social order. The Greek kouros was a mannequin, formulaically composed to provide the essential elements of ideal manhood with strong, even features, long, groomed hair, broad shoulders, developed biceps and pectoral muscles, wasp waist, flat stomach, a clear division of torso and pelvis, and powerful buttocks and thighs. Self satisfaction in the possession of arete was projected by the archaic smile that enliven the otherwise deliberate blankness of expression in these statues.

As the sixth century B.C. drew to its close, the kouroi increasingly soften the hard angular forms of their older brothers, exhibiting a burgeoning naturalism instead. In some late examples, it is almost as if a living figure trapped inside the kouros were trying to break free. The Kritian boy seemed to herald a new style of human representation, but the resulting figure type was a vehicle for the same values as those embodied in the kouros. And the same could be said of Myron's Diskobolos and Polykleitos's Doryphoros for they embody the balance of opposites that Athenians believed was what goodness required. The beautiful for the Greeks was not the erotic, but the good. In fact, they were aroused by virtue.

That is the main difference between the Greeks and us, and that is why a Pygmalionized Brian Sewell only seems to understand the difference between nakedness and nudity as determined through power and sex. Is that because of the contemporary malaise, or is it just another chapter of that complicated post-victorian, love-hate relationships between the British and their bodies. This show will make you think.